-

UNESCO Collection Week 57: Portugal Through the Eyes of a Compiler

UNESCO compiler Salwa Castelo-Branco provides in-depth explorations of this week’s UNESCO releases, Portugal: Music and Dance from Madeira and Portugal: Festas in Minho, both of which she compiled.

GUEST BLOG

by Salwa Castelo-Branco

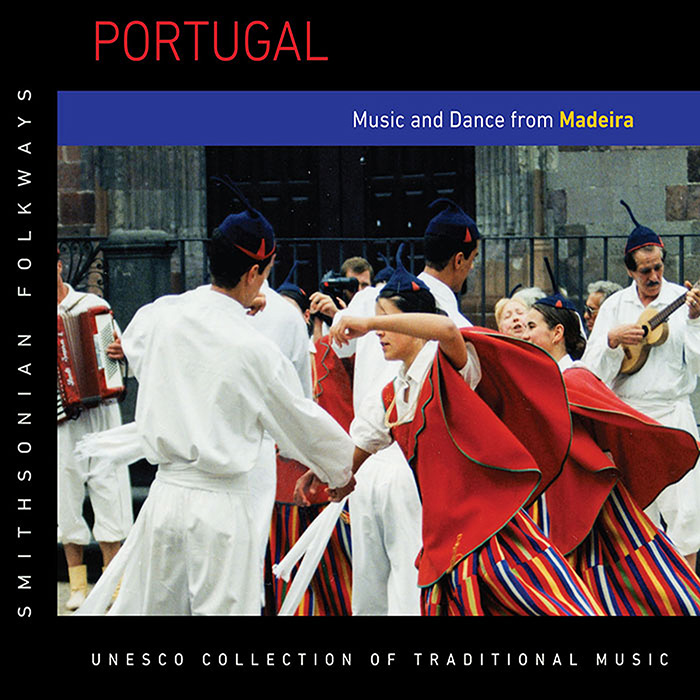

PORTUGAL: Music and Dance from Madeira

The Portuguese Island of Madeira is known as a tourist destination. Less known are its rich music and dance traditions, several of which are exemplified on Portugal: Music and Dance from Madeira. The recordings are the result of collaborative research made in 1996 and 1997 by a team from the Institute of Ethnomusicology – Center for Studies in Music and Dance (INET-md) based at the Universidade Nova de Lisboa and the Xarabanda – Musical and Cultural Association of Madeira. Ethnomusicologists Salwa El-Shawan Castelo-Branco (myself) and Jorge Castro Ribeiro from INET-md, anthropologist Jorge Torres, and musician and photographer Rui Camacho from Xarabanda Cultural and Musical Association conducted joint field research. Castro Ribeiro and I were interested in understanding some of the transformations that were taking place in the music and dance traditions of Madeira, and comparing them with those of continental Portugal. Torres and Camacho generously shared their knowledge of Madeiran traditions and their contacts. Our fieldwork was greatly enhanced by the various discussions amid team members on the ethnomusicological issues that emerged from our research.Guided by Torres and Camacho, we began fieldwork in 1996 in the grand valley of Serra d’Água, home to Maria José Pestana, a tradition-bearer who had been a rural worker in her youth, and a custodian of a repertoire and singing style that had disappeared.

The natural setting was impressive as we went up the steep road, looking down into the valley. The intense sound of a nearby creek added a sonic dimension to the dramatic natural landscape that profoundly contrasted with the urban animation of Funchal streets from which we had left two hours earlier. Maria José Pestana told us about how she learned the songs and singing styles in collective sung poetic competitions (despiques) that accompanied agricultural tasks such as ploughing, weeding, and harvesting. Sometimes the despiques were among people comprising the same group of workers. At other times, antiphonal singing developed between groups of workers who alternated their singing across two different mountain slopes. Maria Jose Pestana showed us with sadness the terraces on the mountain slopes, once intensely cultivated, now abandoned and silent. She also demonstrated her enthusiasm for sharing her repertoire with Xarabanda and INET-md’s archives, as to guarantee its preservation.

Maria José was the first of many musicians whom we interviewed and recorded in different places in Madeira and Porto Santo islands during five field trips spanning nearly two years. We documented local festivities, musicians and music groups: choirs, folklore groups (grupos folclóricos), plucked string orchestras (tunas or orquestras de palheta), wind bands (bandas filarmónicas), and urban revival groups of traditional music (grupos de música tradicional). We also visited local scholars, instrument makers, and musical institutions.

Some of the traditions we documented, like Maria José Pestana’s repertoire, have fallen out of use and only live on in their bearers’ memories and in performances of revivals, like the striking melodized calls of the “borracheiros,” groups of men who carried heavy wine skins from the villages through mountain roads down to the capital Funchal (as heard in track 1, “Cantiga Dos Borracheiros (Song of the Borracheiros)”) and the large repertoire of pan-European ballads that was preserved in Madeira until recently (track 6, “O Veneno de Moriana (Moriana’s Poison)”). In addition, we found newly composed pieces inspired by local styles (track 15, “Encrenca (Trouble)”).

AudioAs we learned about the music traditions of Madeira, we were struck by the pervasiveness of sung poetic competitions (despiques) in several contexts such as agricultural work (as Maria José Pestana’s recalled), men’s socialization as in the charamba (track 5), a genre in which two or more contenders challenge one another’s ability to improvise sung poetry as they accompany themselves on the viola de arame (track 4), or as an accompaniment to the bailinho, Madeira’s emblematic dance (track 5). We were also struck by the richness, variety and ubiquity of different types and sizes of local guitars, from the above-mentioned viola de arame (a plucked lute with one single and four double courses of metal strings) to the five-stringed rajão (a small five-stringed guitar) unique to Madeira (track 9), and the braguinha, the smallest plucked lute, with four metal strings, the Madeiran equivalent of the continental cavaquinho (tracks 3, 12 and 15). José Nunes, a Madeiran emigrant, introduced this instrument in the 19th century to Hawai’i, where it was adopted and renamed ukulele. Portuguese explorers and settlers also introduced similar instruments to Brazil, Cape Verde, and Indonesia. The violin (rabeca) and classical guitar (viola or viola francesa) are also used in some traditional ensembles. The entire mandolin (bandolim) family is used in mandolin orchestras (tunas), as well as in some traditional ensembles (track 10).

Today, many Madeiran musical traditions thrive in the archipelago as well as in its vast diaspora in Brazil, Venezuela, South Africa, Curaçao, Canada, United Kingdom, and Hawai’i. We hope that this CD will stimulate listeners to explore Madeira’s rich traditions in the archipelago and beyond.

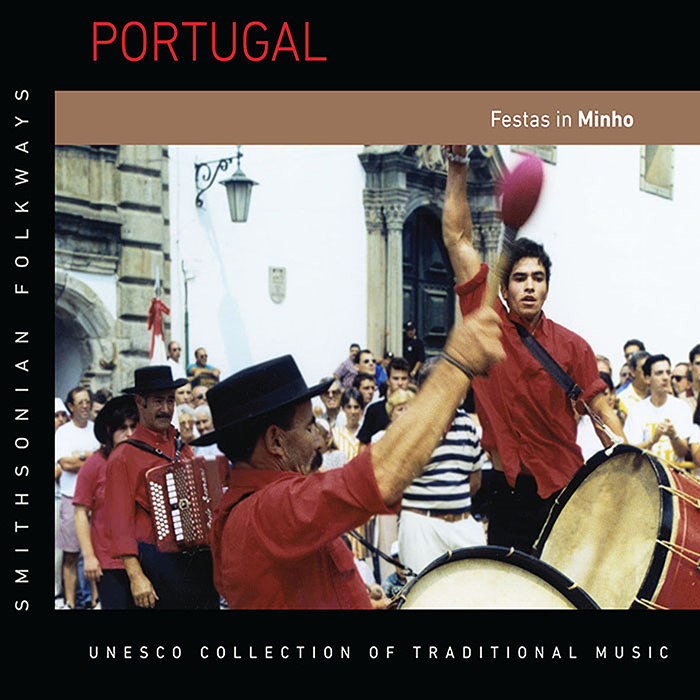

The region of Minho, occupying northwestern Portugal, is known for its green landscape, cuisine, vinho verde wine, filigree jewelry, exuberant traditional costumes, fiestas, dances, and songs. The region claims to be the “cradle of folklore in Portugal,” the place where the earliest folklore groups were founded in the early twentieth century. It is home to a large number of folklore groups and one of the most widespread dance-song genres in Portugal, the vira (CD tracks 1,9,16,17).AudioWe began our fieldwork by interviewing the main concertina players and constructors, leaders of the Portuguese Federation of Folklore, directors of local voluntary associations of concertina players, custodians of sung poetic competitions (cantares ao desafio), and directors of the main folklore groups. In addition, we also spoke with officers of the local delegation of the INATEL – Instituto Nacional para Aproveitamento dos Tempos Livres dos Trabalhadores (National Institute for the Occupation of Workers’ Leisure Time), a government institution that stimulated and supported the revival of the concertina in the region. After speaking with the aforementioned individuals and organizations, we quickly realized the importance of the institutional support of the INATEL, especially in providing incentives for older players to transmit their traditional knowledge by organizing region-wide meetings in which tradition-bearers performed, and by sponsoring the training of younger fledgling concertina players. The successful implementation of INATEL’s policy resulted in the exponential increase in the number of concertina players in the region with many young people learning the instrument (today there are over 2000 players in the region). It also contributed to the reconceptualization of the concertina from an instrument that was regarded by folklorists and collectors as an intruder and a negative influence on Minho’s musical traditions, having replaced traditional guitars in the accompaniment of singing and dancing, to an “authentic” instrument of the region and one of the icons of its identity. Within this scenario, the social status of the concertina player also changed. In the past, he or she was sometimes regarded as a deviant and often persecuted by the church and local authorities for his/her libertarian behavior and for the musical grounding he or she provided for poetic competition that was sometimes a vehicle for social and political criticism. Today older concertina players are honored for their role as custodians of local traditions and younger virtuosi are highly admired by their audiences and communities.

Our interest in the concertina led us to explore one of the contexts in which it is central, local fiestas. Of the many fiestas that are celebrated in the region through the summer months, we selected two pilgrimages, the Pilgrimage of Our Lady of Agony (Romaria de Nossa Senhora d’Agonia) celebrated in the coastal city of Viana do Castelo, and the Pilgrimage of São João d’Arga (Romaria de São João d’Arga) celebrated in and around a small Roman chapel located in the Serra d’Arga mountain range approximately 45 kilometers northeast of Viana do Castelo. In both events, there was an abundance of programmed performances by formally organized groups, especially community wind bands (CD tracks 11 and 12), local folklore groups, and groups of snare and bass drums (CD tracks 3 and 18). There were also many impromptu performances by participants who brought their concertinas, cavaquinhos (small 4 string guitar), bombos (bass drums), caixas (snare drums) and other instruments. They performed poetic sung competitions to the accompaniment of the concertina (CD tracks 10 and 15), local song and dance genres like the vira, gota, cana verde and Rosinha (CD tracks 1,2,7,8,9, 14, and 17), and rhythmic improvisation on the bombo and caixa (CD tracks 3 and 18).

Today, the festas of Minho continue as vital contexts for the performance of the region’s expressive practices such as the ones documented on this CD. In addition, Minho’s music and dance traditions also thrive among the region’s vast diaspora especially in France, Luxemburg, Germany and North America. We hope that this CD will stimulate listeners to explore Minho’s rich traditions in the region and beyond.

UNESCO Collection Week 57: Portugal Through the Eyes of a Compiler | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings