| HOME | ARTICLES | V & P WILLIAMS | CONTACT US |

Voyager Recordings & Publications

Washington Fiddlers Project Panel Discussion

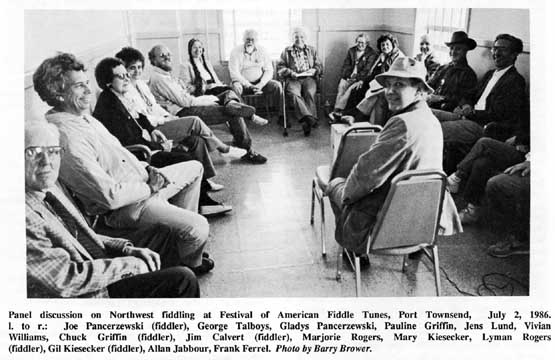

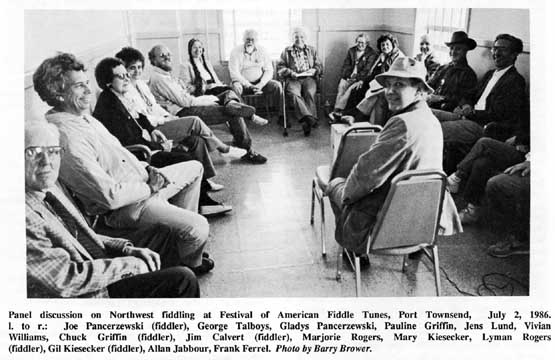

Following is an edited transcript of the panel discussion at the Festival of American Fiddle Tunesl, Port Townsend, Washington, July 2, 1986, as a part of the Washington Fiddlers Project, funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, and initially administered by Centrum Foundation. A version of this previously was published in The Washboard, the newsletter of the Washington State Folklife Council. The Washington Fiddlers Project was started to document the traditional fiddling of the Pacific Northwest. This panel discussion includes a selection of some of the most prominent Washington State fiddlers at that time, moderated and conducted by Washington State Folklorist, Jens Lund; Alan Jabbour from the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress; Frank Ferrel, Director of the Festival of American Fiddle tunes; and Vivian Williams, chief field researcher for the project. This is a long article, but well worth reading to get an insight into the traditional fiddling in Washington and where it came from. There are some great stories and funny anecdotes in this transcript!

FF (Frank Ferrel): The panel officially is made up of our Washington State Folklorist, Jens Lund, Vivian Williams, who has been designated as our field research person, Alan Jabbour, who is working at the Library of Congress with the American Folklife Center, and the fiddlers represented here, Washington fiddlers or Northwest fiddlers, are Joe Pancerzewski, Chuck Griffin, Gil Kiesecker, Jim Calvert, and Lyman Rogers. [Also present were Pauline Griffin and Gladys Pancerzewski.]

The whole idea of this came about because I've always felt there was some need to look at music traditions or the dance music traditions in the Northwest, not to determine what the style is, or what's unique about the Northwest; it's just to find out what it is, or what is here. And I thought that one of the better ways to do that would be to gather together a group of musicians who have been actively playing dance music in the state of Washington, representing the different areas geographically, throughout their lifetime, and many of you who represent this have been playing since before the halfway mark of the century, well into the early part of this century. And with your help in terms of what you can recall and remember and the panelists here who have different points of view about the kinds of things to ask and the sorts of things we want to bring up.

Personally, I have very fond memories of spending many hours at fiddle conventions and jam sessions and contests where the fiddlers we have here today were kind of the key elements - either in organizing or playing. The first picture I have of myself at a fiddle contest was in Ilwaco, and Jim Calvert was the m.c. My first memory of a contest was playing at one in Seattle where Chuck was the m.c., and he kicked me out! He was a judge, that's right, you were a judge, and you disqualified me! [laughter] And I know there are a lot of stories behind the music here, and I hope that we can get some of that out as well. I know that Gil, you spent your earlier days in the Southeastern part of the State, and Jim, you're from the Grand Coulee area originally. Joe came out here in the '20's from the Midwest; Lyman was born and raised up in the Northwestern part of the state by Lynden and Mt. Baker. I think there's as much of a wealth of material here as has been written about and recorded in any other part of the country, and I hope that this will form the foundation for that. And if we're lucky Joe will even show us some things about shooting pool.

JL: Well, I think probably I ought to start with Joe, and I'd like to find out a little about your background, and where were you born, and where were you raised?

JP: I was born in Waseca, Minnesota, and raised in the Western part of North Dakota. My folks homesteaded up there in 1909 - we moved there in 1909, when I was - let's see, well, I've got to tell you, I was four years - five years old.

JL: So how did you end up in Washington? I understand Canada had something to do with that.

JP: Well, that's an awful long story but it's not interesting but anyway, in the last of '21 I went up into Canada and played for a couple of years up there across Canada because it was real good old time fiddling, of course that's what I learned as a little kid, you know, from the cowboys in North Dakota. I knew nothing about music until I went to Canada. Luckily I went to Regina and a man had heard about me and wanted to see me and his name was Francis Kelly, and he was a good violinist. And he said, "Kid, you're a pretty good fiddler but you'll never amount to nothing until you know how to read music.” I never amounted to nothing anyhow, but anyhow, he taught me how to read music, and it was a godsend to help. I found out that there were a lot of places on the fiddle I never knew about. And then in '24, February of '24, my folks had moved to Bellingham west from North Dakota, and I came out there, and it was - The end of old time fiddling come about 1922 and 23 really. The first end of it, anyhow. Because then the young people wanted the fox trot. The fox trot era come into power. And I was right in the golden era because I got to Washington state where there was lots of population, you know, with the dance bands and things, and I was lucky enough to get a job with a good 20 piece band, and played a real hot lick here and there, and fake my way along. But anyhow, I got by. And I played with them until '27, I was here all the way through the big dance bands, and I did play with Pantages as a fiddler presented as an act, and when it became necessary. Sometimes they'd travel by train and bus, and when they'd break down they'd throw me on as the "Yankee Fiddler" they called me, with Eddie Peabody's buddy, and a few more, and we played, and got by that way.

Then in '27 I went back to see my brother, I had a job with a President Lines, I think it was, it was a big orchestra going to Japan and back. We had a week or ten days till the boat came back and we were supposed to go on. So I jumped on a train and went back to Minot, North Dakota to see my brother I hadn't seen in a couple of years, and he was a married man and he talked me into letting go of that fiddling around and [into] shoveling coal. I suppose I'll end up that way too, but anyhow, I hired out the 6th of September 1927 shovelling coal for the Great Northern Railroad. Forty-three years later I retired. Never missed a paycheck.

I befriended some executives of the Great Northern Railroad in their homes by playing for parties for them between '27 and the crash of '29 and '30, and the day I got laid off in June of 1930, I met this vice president in charge of personnel for the Great Northern Railway, coming in to talk with the superintendent. He called me by my first name, Joe, even. I was welcome in his home. He said "Where're you going today, Joe?" I said, "Up to my room. I got laid off." He said "Oh no, you ain't, let's go talk to the superintendent." So he shoved me - he was a great man - he just give me a shove and we went into these offices and he said "Dick," he said to the superintendent - of course he could call 'em like that, I said "Mr. Ritchy", he said "Dick, Joe got laid off. Put him to work in the shop." Dick says "Hell, Im layin' 'em right off every day." This big man looked at him and said "I said put him to work in the shop." He says "Is that so? Get out there in the shop." I never missed a paycheck, all through the depression, on account of the fiddle.

JL: You mentioned that the old time fiddling had died out and that a lot of the music that you played was the new dance. What kind of - before you started playing the new dance music - what -

JP: Well, in Canada, as Vivian can tell you, it was square dances, and schottische, and waltzes, and butterfly, and two steps and all kinds of dances like that. After the foxtrot era come in, and the young people were just wild - it was a good era - wonderful music, I think, in the '20's, you couldn't - why, if you tried to play a square dance they'd have booed you, the dance band, they actually would, you know. It was that way. So I guess that's as good a rundown -

And then, after I retired, I laid my fiddle aside for 31 years, I put it in a trunk in 1939. I was promoted to railroad engineer and the war was coming on and it laid in a trunk for 31 years I never looked at it for maybe an hour in 31 years. And when I retired in 1970 why, I dug it out. I was going to have a hobby. I liked music - of course I couldn't play any more, I hadn't thought about it. And I happened to meet a lady with long braids and brown eyes - I seen her on television. And it give me inspiration. Why, there was somebody playing my old kind of music that I used to. And I never dreamed I'd ever meet her. And one day then about a year later I guess it was here was that lady at Tenino, Washington in the fiddle contest.

CG: A lot of us met there at that contest didn't we?

VW: It was that Trails End rodeo ground.

JP: Yes, in the wonderful place where we played. And she poked me in the ribs with the bow and wanted to know where I learned how to play like that. I was playing a hornpipe or a reel or something I guess, I don't know what I was playing. And I told here "Canada", and so then her and her husband wanted to meet me, I don't know what for, but anyway, we've been friends ever since, or was friends, I guess. No, I'm just kidding. They have made the life for me of my fiddling.

I learned from cowboys in North Dakota. I had the pleasure of showing Vivian where the Nelson brothers - they were - their mother was a music teacher, and they came from Minnesota, and she taught the boys how to play violin by music, you see, and they could really fiddle, those four Nelson brothers. And I had the pleasure of showing Vivian and Phil where their home was where they used to live, way down in them godforsaken hills along the Northern Missouri River breaks.

FF: I want to just - before Joe gets gone here with what he's saying, I don't want people to go away without knowing also that he made a fair amount of money shooting pool. It sounds fun, and it's a joke, but Joe is a bit shy about that around some folks, but there are many times when I had my shop down in the Pike Place Market that he would come wandering into the shop to sit in my office to empty out his shoe. He kept all the money he won in his shoe. Now, you were listed once as one of the top ten snooker players in North America?

JP: Yeah.

FF: They called you the Farmer?

JP: Yeah, Farmer Boy. I got that name when I was 16 years old in Spokane, Washington. I hustled Priest River, Idaho. I had a friend of mine there, and we went into Spokane and I went into a pool hall there, and a fellow said to the operator - it was in the forenoon, in the morning kind of, and he said "Nobody want to play pool around this town?" And he said, "Well, maybe the farmer boy would," he says, and pointed to me. And he looked at me with a sneer, at this kid, you know, see. Said "Do you want to play some?" I says "Sure." "How much do you want to play for?" I said, "Oh, four bits." He said "I wouldn't pick up a cue for four bits." He said "Do you want to play for a couple of dollars?" "Well," I said, "I might." So about fifty-five dollars later he was so mad he broke his cue! (laughter) And of course I had a great laugh.

FF: I understand too that you put a pretty good scare into folks at the National Folk Festival when you went back to Washington to play and you disappeared for a day or two and went to a place called Weany-Beany's.

JP: Beany-Weany's. (laughter) Yeah, it was just a little ways from there.

FF: There was another pool player that -

JP: Naturally, you know.

FF: A big pool hall.

JP: Fifty-two tables in it, yeah.

CG: I remember that. Couldn't find Joe for a couple of days.

JP: That's a sign of a wasted youth. (laughter) A good pool player.

GK?: Sounds like River City!

JP: I've took all the time up -

JL: Well, I'd like to ask Chuck Griffin, who is a fellow Olympian, to talk a little bit about himself. Where were you born and raised?

CG: Well I was born here in the State of Washington; I was raised in central Arizona; we moved down there in 1928. I was about two years old, which I don't remember too much about of course. But Joe was talking about the old time music going out, and the swingtime flapper music coming in. Well, I started playing just about as the flapper music era was out, here come boogie-woogie. Of course, we called it hillbilly music then, and there was some bluegrass around, and then the western swing scene come out, and of course the thing in my life was the Sons of the Pioneers, really, and Hugh Farr playing the fiddle. And at the age of probably 5 or 6 I'd set on Dad's lap and he'd play his fiddle and I'd draw the bow across the strings, and, well, we'd get the tune, somewhat. We had the coyotes crying an awful lot, too, across the creek. On a moonlight night they'd howl and raise cane, and as I look back, I don't blame them. Mother said the only time she ever come near crying in her life was when I'd be practicin'.

But, the first thing I ever learned to play was a schottische that my dad played, in fact, he played a couple of them, and in fact in later years we recorded them, if I'm not mistaken. And a few of the old hoedowns, but the first tune I can remember is an old schottische. Now Daddy’s tunes were more or less Ozark style of fiddling. He played a lot like Pete McMahan. Now I'd ask Daddy, I'd say "Daddy, what's the name of that tune?" and he'd say, "How the hell do I know?" And we had a nice gathering of company one Sunday night, and somebody asked Dad to play the fiddle, and he played a couple of tunes, so I asked him "Dad", I said, "Why don't you play 'How the Hell do I know'?" (laughter) He started to get mad and mother said "Sit down, old man, you taught him." (laughter)

But I got to playin' and more interested about the age of 10 or 11, I think I played my first dance. And a few years later I got tangled up with about a ten-piece band in the city of Phoenix, a group called Buster Phyte and his Western Playboys. It was undoubtedly named after Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. We had a radio program over station KPY in Phoenix, and we played, oh, if I can remember, down on Washington Street was a big ballroom. Oh boy, wonder if I can remember the name of it. You, know, you get to be so old, your memory's about the second thing to fall flat on you. But I was down and played that ballroom a couple of years, and I picked up an awful lot. Now this old boy didn't want to spend too much money for musicians. To have twin fiddles, he says "You can do it yourself." He taught you to play a lot of double stops. In fact, he didn't teach you, he forced you. But today, you hear just a tremendous amount of these young kids playing all that stuff that was such a struggle for us back in the late '30's and early '40's.

I come to the Northwest just the early part of the war. My folks moved north and of course I come with them. And got tangled up with dance bands in Eastern Oregon and over in that part of the world there are a lot of Scotchmen. They used to have a dance in Mayville, Oregon, twice a year with all the Scottish Americans, playing all them fast reels, and them old Scotsmen get out there and dance to that in their kilties, kick their heels high, and you have to play some pretty fast music.

Now I went in the service, and come back and then lived at Fort Lewis, and I got tangled up with a group. Played the Tropics Ballroom. How many years, Mom, did we play there?

Pauline Griffin: Four. Then you left for overseas.

CG: Yeah, and we played in, let's see, we played some in, was it the Civic Auditorium in Seattle, no I guess it was the Ballroom.

PG: Dick Parkers.

CG: Dick Parkers, Shadow Lake. It came to 15 pieces in the band, depending on the size of the hall we were playing, ten or fifteen pieces. We got to playing a lot of this Western swing stuff.

I went overseas to Korea, in 1951. I come back and the kids started coming. We had one, and somehow or another two come along, and it wasn't too long after that we had three. And when it cost more to get a baby sitter than you could make playing the fiddle on a Saturday night, I quit playing dances! I stayed away from it till heck, back in 1969 I got hurt. I was working for the state and got hurt and had to have back surgery, and I run onto a fellow, I don't know where he found me, but his name was Neil Johnston. Neil got me by the little hot hand and started carrying me around to some of these jam sessions. That's why I got into this contest circuit. Contesting makes your music better; you get cognizant of what you're doing and what you're not doing. I wouldn't trade my experiences I had in the contests for all the money in the world. But basically, my preference in music of course is Western swing. I just love to hear them twin fiddles or a good double stop get out and start kicking out some of the dance music.

Today, as Vivian once said, we now have in the contest circuit, a canned music, with every fiddler sounds just about alike, they're all working for the same thing, the best Sally Johnson, the Sally Goodin and Clarinet Polka in town, and it all sounds pretty much the same. In fact, after six days back in the hole, some of them tunes get pretty boring. I remember last year when I was a judge at Weiser, when the minister give the invocation before starting the program, before the judges played, Dale Morris was standing there and he bowed his head, "Please Lord," he says, "no more Sally Johnson." (uproarious laughter)

So I like to come to a place like this, for the simple reason that here you get other styles of music that you're not about to here in a fiddle contest. But strangely enough, you have them around the country. If you attend some of these contests out of state and far away, well here come some of these tunes and it's kinds of nice to know what they are. You pick up a lot at a place like this.

What's next?

JL: Well, I guess we go on to Jim Calvert, find out a little about him.

JC: Well, my dad homesteaded in the Big Bend country, which is still called Big Bend, and of course Coulee City was our closest doctor in 26 miles, I think it was. So mother was moved to Coulee City, and I was born there in 1905. And she was a kind of a midwife - she delivered all the babies around all them homes, you know, and the nearest doctor as I say was 26 miles, either Mansfield or Coulee City. And Mother took care of one of these cases down on the Columbia River Breaks, and in those days the girls, why, the girls stayed in bed about ten days and Mother went down delivered the baby and the doctor finally got there of course and everything was all done when he got there and he got the money and if he had any, why, she didn't get any. But he had an old fiddle a-hangin' on the wall, and he give it to us for delivering the baby.

JL: What kind of music were you playing back then?

JC: Well I was just learning, you know, and I had thing about oh, two and a half years before I could tune it up.

JL: Was there anybody in particular that you were learning from or working with?

JC: No, just my brother, a pretty good dance fiddler, he wasn't a show fiddler but he was a good solid what we call a dance fiddler, time-wise. So I was about 12 and a half years old, and he was railroading in Pocatello, and he came down to help us harvest, and anyway, he tuned the fiddle up. I could get a tune out of it, but I was just stuck. And by the time I was sixteen I was playing for dances, and I've playing for them ever since, up until the last ten years, fifteen years. It's been all dance work, this has been my work.

Well, we played there and then we went to Southern Idaho and I played what we called kitchen sweats. And we moved the furniture out and danced till 4 o'clock in the morning.

CG: You betcha! I've been there!

JC: But I've had some good dances, never been drunk in my life.

VW: Not too many of us can say that.

JL: Did you notice a real change in the kinds of music that they were playing....

JC: Not really. It seems like when I come out here, I had the only square dance in Pierce County. We had a dance that run 10 years. And I moved into a hall at Milton, not Milton but just out of Tacoma there, and we played there for eight years, and I averaged over 400 dollars a night. 400 dollars - I mean 400 admittance, people. And I'd ask people to come to the dance and they'd say, "we can't get in". And they couldn't. It was just chuck-a-block. And we had dances that run Century Ballroom, 2500 people. And at that time, that was the dance area around this country, was just packing into square dances, and like I said, I had the only square dance in Pierce County. And a fellow by the name of Lindgren had the only square dance in King County. And I run there for 8 years, and then we got into jangle - he was lettin' the girls in free, and that brought the rowdy boys.(laughter)

JL?: From Fort Lewis, right?

JC: "If you don't need the money," I said, "we do." He was paying us scale, and I said -- "Well," he said, "they kind of want a younger band." He said "they want to, you know"-- Well, I think that Cherokee Jack went in there and played three dances.

CG: The trouble with Big Cherokee is he'd run them off in three dances anyway.

JC: Yeah, it took him about three dances to run 'em off. Now here I'd had 400 people come in and he run 'em off in three dances. Well, so much for Cherokee, the poor devil's gone now and I shouldn't even mention him.

CG: Jim, don't you think that about in those years - this is when we were playin' heavy - here come along lots of bowling allies and television, and daylight saving time, and the dance business fell flat overnight. Late '40's, early '50's.

JC: And a lot of the dance bands played to the band. You know what I mean, Chuck, don't you, and rest of you old fiddlers. You played what you liked to play. And they was having a dance down at the Evergreen,

CG: Yeah, that was a popular dance.

JC: Yeah. And I went down there one night when I happened to be off one particular night and just, you know, lookin', and I went down there, and told Leo Smith -- did you know Leo?

CG: Oh, very well.

JC: And I said, "These boys are going to ruin your dance because" I said, "they're playing to themselves, not to the crowd." I said "It's eleven o'clock and you haven't played a waltz." And I said "These people come down here to dance everything," and I said "They're not doing that." So, sure enough, she closed up, beer and all, she went.

In '60, I think, or '65, the dance business then had started really down. Up until then, why you have had big dances.

VW: So you were doing a mixture of square dances and then like waltzes,

JC: We had swing, Western swing, square dances like I say,

VW: And then did you - polkas and schottisches?

CG: Oh yeah, all of those.

JC: They were about as popular then as at my dances as they are now. And I talked to these guys that's - I don't know how many of you are mixed up with square dances but I'll say it again, I ask this guy "Why don't you hire live music?" "Oh", he says, "you guys can't play our kind of music." And I said "Who do you think's making the records?" (appreciative grunts from everyone) And then when they started dancing square dance to This Old House - that kind of -

VW: Around the World in 80 Days. That's when we quit playing for Federation square dances, when we had to learn to play Around the World in 80 Days.

CG: Or El Paso.

JP: You're right, Jim, about musicians playing for themselves instead of the crowd. I tried that once in a big band.

JC: Yeah, you get playing what you like, see, and not what they like.

JP: I sure got my comeuppance quick.

CG: It don't take long.

JP: I played a hot lick all through the chorus so they couldn't dance to it, you know, but it was real hot.

JC: I'll tell you another thing that happened that I found out from that dance because this has been my life work. But never take any money over the stage. Never take any money in the can, never let anybody give you any money, because if you're not making enough money, quit. The time when he comes in and gives me a dollar to play a tune or five dollars, I'm in his employ. Where's he at? He's out having a drink. Then he comes in and he says "You haven't played my tune." What are you going to do?

CG: Play it again.

JC: You hired out to him when you take his money. I made it a fast rule, I says "If you don't like what we're playin', go down and get your money."

JL: I'd like to get Lyman Rogers to talk a little bit about where he's from and how he got started playing the fiddle.

LR: Well, this has all been very interesting. I've been listening to Chuck and Jim and Joe, and I couldn't help think the truth of the difference in styles and times that each of us has experienced. I was born up in Whatcom County as Frank told you a while ago there, on a timber claim in the shadow of Mt Baker. And I was a young lad - 2 and a half years old, just above crawling age - when we moved to the flatland out by west of Lynden. And that country was in an emergence movement at that time. They had come from the pioneer time to the time when the land had become cleared, and it was being farmed, and they were working intensely as tillers of the soil. Between Lynden and Blaine and Ferndale, triangle area there, there was about 30 square miles of nothing but just farmland with no activity except what they could make for themselves. So there come a point where they needed recreation, and needed outlets for their other interests than just working behind the plow, and they began to build grange halls, they built Oddfellows halls, they built churches and public places for activities away from the established towns. And in those days we had no transportation but horses - before the automobile days, 1910 to 1918, they finally were beginning to get roads enough that they could put Model T's on them and they could get to town and they felt that they were really living then. But up till that time, they didn't have much chance for social expression, so they begin to agitate or begin to look to the various areas where they could gather for their social life.

Well, they established the Granges under the sanction of the Pomona Grange, it had jurisdiction over the various granges. Well they established a grange about every eight miles. There was one at Haney, which is right out of Blaine about five miles and then the next one was Dakota Creek and the next one was Delta and the next one was North Woods and then on down to Meridian Grange and those various granges became focal points for the social life of that farming area. And they would go there for their recreation.

Well, they had to have some music. They wanted to dance and wanted to do something besides work and toil, so there come a urgency there for an expression in the style of recreation that they were interested in which was dancing or singing or whatever they did with music. And there was a shortage of players. Well, they had three fiddlers in the county that I knew of at that time, I heard about through my parents: Jess Crawford, Johnny Hawkins, and another man out of Lynden that Joe knew, Alvin Weidkamp. Those three people were the fiddlers that they had, the people that had bands going, and they were looking for musicians.

Well, my father wanted me to get something out of life besides just knowing how to drive a horse or something, so he wanted me to start playing music. None of my relatives, ancestors, that I know of, were active in music, and Dad always thought that there should be somebody that could play some music or something besides what you heard on a cylinder phonograph. So he started me out on a violin. In those days it was a violin. And I went to town and took lessons and became more or less a formalized violin player, but I heard about this fiddling going on, playing for dances and so on and my interest began to shift in that direction and finally the teacher told me that he thought I'd make a better fiddler than I would a violinist, and that perhaps he'd done as much for me as he could. So I was about 12 years old at that time and I'd going to him for five years, so at 12 years of age I began playing for dances, and filling in for these different ones and by golly, the first thing I knew I was playing more times a week than the folks wanted me to be out, away from schooling. And I ended up there playing for each of the Grange halls, at different times of the month. I had my own band, five piece, which was small as far as bands go as Jim and Chuck have been talking about, but that's what we had up there to word with. I had fiddle, piano, banjo, drums, and either a saxophone or trumpet. And that was the music that we had.

And what did we play? Well, we had to play something that the people could relate to. We didn't have radio, we didn't have any way of communicating except the party line telephone, we were 18 - 20 miles from the nearest town so we didn't get into town to see what was going on, we had to make do with what we could pick up on the side, and put it together, and something that the people could relate to. Well they set a pattern in their dance choice or their priority for dances, they wanted to dance a waltz, a mazurka, the square dance, the three step, the two step, and the schottische. They hadn't heard much of the polka at that time. So we developed a pattern of tunes that would satisfy them. We found that we had to play something that they could relate to in their mind, that they could be playing it over in their mind as they were dancing and so on because they kept requesting those pieces. So we had a pretty set simple repertoire of tunes, probably 35 - 40 tunes that we played over and over and over, and that was our bill of fare.

Until the radio came out. Then we begin to broaden out and I got involved in the high school effort of music, operettas and so on, so the board of directors of the school where I was attending set up a special class for credit in music under operetta, and music, and I got a credit for that in my diploma from the high school. Well, I kept at it then in music until 1934. I had to come to Seattle because of medical reasons for my wife, who was needing attention down here, and we moved to Seattle and that was the ends of my music for - from the standpoint of the activity I was used to doing up there, that was the end of it. And I didn't get back into music until about the time Joe mentions; I put the fiddle away in 1939 and didn't take it back out and begin my activity again until 1969 or 70.

And I had heard about Weiser, Idaho so we went over and I retired from the job we were on and my wife retired at the same time and we went to Weiser to see what was going on. Well we caught fire on what we heard over there. And at that time we were driving a camper and we were looking for a place to camp on the Junior High School grounds and there was a row of cottonwood trees clear around the place. Well I found one opening that there wasn't a camper or anything in, and I backed into that real quick, saved that spot for myself, and there was an outfit going over here and they were playing really gung-ho. And on the next side there was another outfit and they were going strong, really going. And out in the center they were really going. I found out later this one side was Junior Daugherty from New Mexico, and the one on the right was Chuck Griffin! He had an outfit going and I mean they were really good. I caught fire.

I went to Jack Link, the M.C. over there and asked him how I could get involved in that and he says, "Well, they're going to have a convention in Enumclaw the following August." This was in June. So I'd go there in August so I could find out. So I went there in August and I got acquainted with the ones that were running the organization and I joined and I became active and I went back to Weiser the following year, and each year since that time. But at that time I didn't know who all these people were. Jim Calvert was out in the field and Vivian Williams was out in the field with her husband at that time and Elmer Coffey and Joe Pancerzewski, and the whole bunch of them were all playing that I became friends with later, but I didn't know them well at that time. It's something that has stayed with me and they had still been active in it all this time, and it's been a movement that has been part of our lives.

JC: I want to mention one other thing. Now, I can't read music, but I would play these dances and never play the same tune twice, and play as many as a hundred and five tunes right off the top of my head just as fast as you could -

JP: Easily. And more than that, Jim, more than that.

JC: No sheets or nothin'. Never written down.

CG: I can read a little but not enough to hurt my fiddlin'. (laughter)

JC: I was going to have one of my series of operations, and asked the doctor, I says "Is this going to hurt playing the fiddle?" And he said, "Well, I operated on two guys here a while back," and he said "I think they're both playing the harp."

CG: You know, Lyman, you come into Weiser in the best years we ever had. They were fantastic. We don't have that fun over there, in fact there was nobody in the practice room this year.

LR: Chuck, not only from the fact that they were playing good stuff, but the people that were coming there at that time were all interesting. They were actively involved in it and they were

VW: They were interested in each other's stuff and they didn't all play the same thing. (general agreement from several voices)

CG: There was an interest there, a mutual feeling all the way around, that's not there now.

LR: There was a great movement, it really was.

CG: In fact, I think the thing will die if it don't change.

LR: I gotta mention one other thing. In 1970, as I said, in 1969 - 1970 I joined the old time fiddlers there at Enumclaw, and I met Joe. Come to find out he'd been over at Weiser when I saw him the year before. So we got to comparing notes there, and I mentioned the fact that I had been playing for a fellow out of Lynden there occasionally on a Saturday night at the Delta Grange Hall. He'd be short a player and I'd go fill in for him, and he said "Well I did too." He says "I used to work for a guy over there." He says "His name was Alvin Weidkamp." I said "Well, you played the opposite Saturday nights that I did." And this was back in 1923, 1924, and I hadn't met him till 1970. I knew he was playing there but I had never met him. And here was Joe-

JP: Bill Sherman let me off to play that, help Alvin out, -

LR: And that was the Saturday nights I couldn't get over to help him. And Joe went over and played and I didn't meet Joe until 1970.

JL: Well, I'd like to ask Gil Kiesecker to speak his piece, he's been quiet so far.

GK: Well, it goes back quite a ways too. I was born in 1916, and about the time I hit the second grade, why, I was picked for a drummer, from the school. And we went in and played in a band, and had a little orchestra and I played on the WSC station when I was about eight years old. And I kept that up for a little while, also, my dad played the fiddle a little bit and he taught me to play the old pump organ. We always went to dances Saturday night and I'd play this old organ until I'd be played out about midnight and people's come along and pump this thing for me so I'd keep chording. Well, that went on until I was about 10, then I always could start a tune, you know, on the fiddle, and about at ten years old I was able to play enough of it to get by.

And of course back in those days everybody wanted to hear you play so they'd encourage you to play.

We were in the country east of Asotin County, in a little town called Anatone, that's where I was born. It was a farming area, and a lot of homesteaders in there, stock country and all, and we used to ride horseback ten or fifteen miles, you know, and play for the dances, sometimes up into Oregon. And in bootlegging days, you know, they'd have great turnouts there. People came in for hundreds of miles there around there, even from down from Enterprise. We'd ride horseback in there and we'd start playing at dark and keep going till daylight. And that was during the Depression times, pretty hard times in there. I used to go along and the only two people that I knew that played fiddle there, one of them was Dad and the other a farmer there. And they kept me along down in these old stock country to play, and we'd strap our instruments on our back and get on the horse and ride away. I played the steel guitar. And that got by for a while, and then about fourteen years old, why, I started playing. Cause they'd have me come back; they got tired of goin', you know, the old fellers. So I carried on until about the time I graduated; I even played in dances in high school and all that, and I graduated in '35 of course, and kinda moved away from there, gettin' work and one thing and another.

In 1940 or so I went into the service. I was there about five years in the army, and when I come out, why we moved back to Seattle. Then I kind of got away from playin' for dances and things like that, and I joined the fiddlers in 1975 I guess, and started back in playing again. After spending about 25 years in the grocery business, why it kind of took all those tunes out of me, working day and night, you know, and things like that. So I kind of had to start all over again. Tunes that I had learned to play were quite old fashioned, and so I kind of brushed up on them, learned them a little bit over.

The old dances we used to have, where I learned to play one step, two step, three step, schottisches, polkas, you name it, you know, a lot of the people that were homesteading in there, you know, were kind of foreigners. Even my grandparents came from Germany. And they had dances of their own. You picked up pretty much what the people had, you know, that's the kind of step that you gave 'em. It was all in that style, so that's the kind of style that - there was a lot of construction work, lumber yards and mills in there, you know, and these people were Scandinavians, you know, and those were the kind of people I kind of liked to play for.

They've got a swing in their dance that really sets me off, you know, and I get to goin'.

CG: A swing like that should be on the back porch!

GK: One thing I like is good timing, you know, and good dance tunes.

VW: One thing, all of you have mentioned that after - except Jim, you're the only one that never really quit, but everybody else went through a period where they didn't play much fiddle-

JC: Yeah, let it go for a while.

VW: And then, you've been crediting the Weiser contest and the Washington Old Time Fiddlers jam sessions and contests with being a sort of a way of getting back into fiddling. So obviously it's been a very constructive influence in getting old time fiddling going again. But don't you think that the contest scene has also changed the fiddling?

LR?: It changes very radically.

CG: It's changed, liked we said before, the music now all sound alike. You know, you don't get anything bright and fresh and different. It's all basically -

VW: You think they're all copying each other.

JC: Yeah.

GK: It's just changed the whole situation pretty much.

CG: Mark said something last year at Weiser, he said "I hear lots of Herman Johnsons, I hear lots of Dick Barrettts, I hear lots of Mark O'Connors," he said, "but I don't hear any individuals." And this is what has happened.

JP: Well, I claim that, the first time I went to Weiser, and heard them fiddling, I said to Marshall Jackson, my accompanist, I said "Well don't they have any fiddlers down here? I hear lots of syncopation and improvisation. But you couldn't dance to that music if you was to be cut. I was used to fiddlers if you couldn't play dance music you weren't any good. Have you tried to dance to Sally Goodin or Dusty Miller or -

JC: It's not danceable any more.

CG: If you think it was bad then, Joe, you haven't been to Weiser for probably 8 years.

JP: But those people that are so great now - and I like to play some of that music, too - if they go to Canada and play up in Shelbourne, Ontario, they don't get the first cut. They're all cut out.

CG: They're all done.

JP: Cause they don't play tunes.

CG: Well, if you thought it was bad then, you ought to see it now.

JP: Is that a fact!

CG: Yeah, I guess '74 was your last year, wasn't it.

LR: When I played dances up in Whatcom County they even requested certain dances. They came there expecting to dance a certain type of a dance and they had you play that type of a dance. If you didn't get to it before they requested it they would see to it that you did play it, and it had to be something that they could relate to. They were leaving their hard work at home and they were going out for relaxation and they wanted to relax their way. And it had to be something that they could relate to. They couldn't dance to Sally Johnson or Sally Goodin or one of those pieces, or some of these fast rags that they've got like Wilds Fiddler's Rag. They'd have just sat.

JP: It's exhibition fiddling.

CG: They would sit down.

LR: But they wanted square dances, they wanted mixers, they wanted mixers the worst way there; it had to be certain two steps that were popular.

JP: So they could dance to it.

LR: Right. Or partner change dances and so on. And you played the type of music that would go. And all of a sudden they would want a specialized dance, because they wanted to -

JP: The Rye Waltz.

LR: Right. Or three step or -

JP: One step.

JC: I bet you half the fiddlers right here today can't play a three step.

JP: I'll bet they can't either.

?: And the Varsouvienne, and the Rye Waltz.

LR: Those pieces were requested, and you had to play those dances. Later they become pattern dances, they called them pattern dances. But those people pioneered the pattern dances in their search for relaxation from the day's efforts that they were puttin' forth on the farm and they had to have recreation. And that's where they got it.

JP: Rags - Jim Calvert will tell you - rags were played so they could dance to them. They didn't play them a hundred miles an hour. Why, how could you dance to them? Rags are supposed to be played slowly. Scott Joplin says that right out of his book.

LR?: When you're playing a contest, you're playing to three people. They've got five judges and they throw two of them out, so you're playing to three people. When you're playing to a dance floor you're playing to a hundred people.

JP: Or five hundred.

VW: It's kind of something that's built in to the contest situation. Even though they talk about danceability in the rules, they way the score sheet is set up, danceability is only a small fraction of what you're judging for.

LR: But there's a differentiation between the type of music that contesting brings out, and the type that the old dance bands used to experience. I played in that same group that Joe mentioned; this Bill Sherman had a dance band out of Bellingham there, and occasionally he would have you come and sit in with him, and on a special job he'd do there at the Pioneer Hall in Ferndale, or out at Birch Bay. And those dances, we were playing the tunes that the people could relate to. Now these contest tunes people can't relate to them.

VW: The fiddlers are playing for each other.

LR: They - the listeners can name the tune that they're playing but they're not relating to that tune.

GK?: It says old time ability, and by God, the judges pay no attention to it.

LR: Well, it doesn't - the type of tunes that win doesn't lend itself to that particular factor. It just doesn't do it.

CG: You can only use that column for anymore for a bonus column. Just say this guy did some nice little things here, I'm going to give him some extra points here, and put it down in the ability column. That's all you can do.

PG?: Not enough to let him win, though.

CG: Well, sometimes it only takes one point to win.

JP: I tell you, I've won a lot of contests, in a very easy way. I shouldn't tell you guys this, but I and Dick Barrett - he does the same thing. Instead of tuning your - first thing I asked down there at Weiser when I went down there, I says "Everbody tunes to standard pitch, don't they?" "Well, what do you mean?" The committee didn't even know what we were talking about. Well, that's a finest trick in the world, to tune your A to about a B, or a little higher than a B, all the way up. And boy, you fiddle will just sparkle, you know, and them judges sit back there and say "Boy, ain't that somp'n." You gotta have your own accompanist to tune up-

JC: Better when you're playing on the high side of standard.

JP: Sure. Otherwise, you can take your fiddle and go to the piano, why it's bong, bing.

PG: They don't want that.

JC: I laughed at Dick one time, he said "I don't play for the judges", I said "Just who the hell to you play for?"

JP: That's who you play for.

JC: He's talking about not playing for the judges - that's the first thing you do, I said, you not interested in anyone else.

JP: They don't pay the money.

CG: Dick used to come to Pauline when I was judging and ask "Do you think Chuck will like this?" And he wasn't playing for the judges!

JL: Well, we all sort of seem agreed that contesting and playing for the judges and so on has really struck quite a blow to fiddling around here. That seems to be what we've been talking about.

VW: Well, I don't know if it's struck a blow to it, because dance fiddling, if there's not a demand for dance fiddling, that's where the blow is. You can fiddle in the fiddle association jam session, you can fiddle in your or someone else's living room, or you can fiddle in the contest. It's an outlet.

LR: -- will always make the contest popular, because he wants to win something. But it doesn't make for the type of music that everybody else can relate to, and do in the way that will keep it alive. But your contest fiddling is something that people will search for, a chance to express themselves in a way that you don't when you're playing for dances and so on. But it's an outlet that's helping in the movement, and it'll never kill our old time fiddling. But it's something that won't make our old time fiddling either because it has to be something out of here that makes old time fiddling.

JC: To give you -- now, Mark O'Connor is a very unusual fiddler.

CG: A very talented young man.

JC: Very, very few of them ever come along like Mark O'Connor. But here's what I saw down at the fair. Now I played the fair about eight years, and I could tell you a story about that too. But I played the fair right behind the shop, with a darned good organization out of Texas.

CG: Oh you bet! A fantastic bunch.

JC: We enjoy hearing them every time we hear them. But anyway,

I would come on right behind them, use their equipment, and hold the same size crowd or bigger. And who would come on behind me? Mark O'Connor. He would have 20 people. He wouldn't have people sittin’ out there listenin' to him.

CG: I have found that on shows or anything like this a bad Turkey in the Straw will draw more attention than all the good Cotton Patch Rags .... You play them something that they identify with. Cotton Patch Rag and Sally Johnson don't do it.... Contest tunes do not make good entertainment music. That's what you go to hear.

JP: Vivian and I and Phil were playing down at the - in Portland Oregon, remember that time when the - I can't remember what the name of it - there must have been 3 or 4 thousand people. And I played Irish Washerwoman to them. Everybody just roared and clapped. It was wonderful. And I do a lousy job of playing that tune in the first place.

CG?: I'm sure you do, Joe.

JL: A lot of people know that tune, too.

CG: Well this is it. You go out today and play the fiddle to entertain the crowd, you can get up there and play all that old contest music you want, but you get up there and blow that Orange Blossom whistle one time, and them people are way up there. They don't come down till you're through. Hell Among the Yearlings, Listen to the Mocking Bird, Turkey in the Straw, they love that stuff!

JP: Here's something I can't understand, I told it at Weiser. Well they don't like me cause I called them a bunch of crooks but anyway, they had five judges, so they throw out the high and low. I said "Well, why do that?" Well, one might be too low and one might be too high. I said "well, you've got three left, maybe there's another too high and too low." Throw them two out then, one's bound to be higher than the other one, or lower. He says then you'll just have one left. There's as much sense to it, isn't there?

JC: If you can't trust them in the first place, better not hire them.

CG: Mostly the younger generation of fiddlers, they don't like to play waltzes. They're not fast enough and not -

JC: They want something that has some zip and go to them, see.

CG: At a contest they'll get up and play their hoedown, and then they'll play about that much waltz, and slide into Cotton Patch Rag. And I think it's basically because most of them don't like to play a waltz. It tells too much of a story.

JP: I think we're being a little hard on the young people, though. They don't have a chance to know what they're trying to interpret.

CG: We're not being hard on them, Joe, I'm not putting them down.

JP: No, I'm not either.

CG: We're not being hard on them, they're just shall we say undereducated. They haven't lived long enough to really see what's going on.

JC: You know what I mean, when you go to a contest and have a - we'll say an eighteen-year-old kid judging a sixty-year-old man, I don't think you can ----- and do it right.

LR: Well there's another factor in this too. The older of us fiddlers came up at a time when we didn't have access to the music that these young kids have got nowadays. They've got the radio and the TV and the various places they go, they get exposed to the type of music that we didn't know existed in those days. And I don't mean to disparage or anything of the kind. But we came up when we had to learn to play the music that pleased right then and there and that didn't have to be something that we could throw away and turn around and learn a new tune and still be in the contest. Because if we had to throw it away we weren't in business.

JP: That's right.

LR: We had to be playing something that was -

CG: And on top of that, Mom and Daddy's got a lot more money to buy good instruments with, too. I learned to play on a gourd and I imagine each one of you guys did, more or less. Today the kids get 2500 - 3000 dollar fiddles to play on.

JL: The young kids don't have an audience among their own age, either.

JP: No, they don't.

JL: They don't play for their dances, they don't even have people that listen to them other than the other ones that -

CG: Yeah, this is the thing, you see. If they had an audience their own age out there dancing to their music, they would soon be playing danceable good music.

JP: And they'd be good players at that.

CG: Oh, don't tell me that these kids aren't fantastic musicians.

GK?: I think we've done a fantastic job finding these youngsters and getting them taught how to play, I think we've done a great job.

LR: We'll have to get them into a vein of other types of music or -

CG: Well, I think that eventually, Lyman, -

LR: It'll burn out.

CG: It'll burn out to a point, but there'll always be those that started out. Now you take the kids in Spokane, every one of them learned to play when they were taking lessons and listening to guys across the border up north. They were playing Canadian fiddle before they got the Texas long bow. And they well get back to that one fine day. In fact, Tony Ludiker plays one hell of a Money Musk. Boy, when he wants to turn that on, he can lay out a good one. There's a fiddler over in Yakima, John Melnichuck, most of you know John, John plays one of the best First Century Reels you ever heard in your life if you can get him to play it, it'll just bring tears to your eyes. He played Canadian music long before he ever started off on this. And old Myllie Barron, if he keep laying what he was born and raised to play, he'd still be number one in the Seniors at Weiser! But no, he has to play Sally Johnson, Clarinet Polka and Ookpik!

FF: Do you think that Canadian influence is pretty strong, mixed with the Western swing, I mean do you think that -

CG: It this part of the world, it was. Today, we have too much - When Benny Thomasson - and I loved old Benny Thomasson dearly, don't get me wrong. But when Benny moved into this part of the world, he brought with him what Barret and them guys was bringing up from Texas spottily to Weiser. There wasn't many of them then. But Benny came in here, and it wasn't a year later, they were all playing I Don't Love Nobody. They were all playing Sally Johnson.

LR: Cotton Patch Rag.

CG: Cotton Patch Rag. See, they all went for this, every one of them. And the kids that was winning the money at Weiser, it still is, and the youngsters, all the contest money, is going to this style of music. And you can't teach a kid to play Angus Campbell, and Here's to the Ladies, and Poor Girl Waltz, play them in a contest, and expect him to keep on playing that stuff when Sally Johnson and Martin's Waltz and Clarinet Polka's winning the money. He's going to switch over. And even Myllie must be in his second childhood because that's what he did. Spoiled his music, really. Love that old man, but that's a shame.

JC: You take of proof of playing, it's just like adding two figures, if you add two and two is four's perfect, see, and if you get up there and play the simplest tune, and play it good, they can't give you anything but a good score.

CG: Right on;

JC: But if you get a guy of course that plays a little more difficult tune, and does the same thing, he's going to win. But that doggone Bill Yohey's got a room bigger than this place here chock full of trophies, and what does he win it on?

JP: Snow Deer.

JC: Amazing Grace. And Snow Deer, yeah.

CG: But when old Bill plays, and you get through listening to him, you know you've heard something.

JP: You betcha.

CG: You've got to give that man credit. Last year when I was judging that contest, he was playing in the Seniors, there was only one out in front.

JC: Why sure, and he was there. And he was playin' Amazing Grace, I'll bet.

CG: No, he didn't play Amazing Grace, but he played Sweet Georgia Brown, but it sounded good, and his version of Durang's Hornpipe ain't shabby either.

JC: He still has his room full of trophies.

CG: You bet he has.

JC: He done it all with simple tunes.

CG: But he's not pickin' up the number one trophies like he used to. Now I was back in New England last summer and I played in two fiddle contests. And I heard more Sally Johnsons and Sally Goodins back there than you would hear here. In New England they've gone this way.

JP: Is that a fact!

PG: Yes.

CG: That's a fact. In fact I tied for first place in a fiddle contest in Maine last summer, and I used Soppin the Gravy for my hoedown.

JP: Sure.

CG: And I don't play it that good. But you know Donna Hines, plays a hell of a Texas fiddle. And what was the boy that come out of Maine then he went to California here, was a judge at Weiser several years ago -

GK?: Fred Carpenter.

CG: Fred Carpenter's the name I'm lookin' for. Hell, you can't tell him from Dick Barret when he gets to going.

JC: Is that right!

CG: Yeah, and he's a native son of the state of Maine.

FF: Maybe then the contests aren't the best barometer of what's-

CG: Right. Now it is the best indicator of what's popular amongst the contest circuit. But it's not proven anything. And I hate to see - now this just chills me, when Sally Goodin played in a middle-of-the-road phase, against the First Century Reel, and the poor guy playing the reel's gotta go down the tube, because two of the three judges don't know what the hell they're listening to. And this is what's happening all over the place.

FF: Well let me pose a hypothetical question. If you were having a fiddle contest, say, in 1938, here in the state, what would be the tunes?

GK?: Back in 1938?

FF: Yeah. What would be the - what would they consider the -

VW: The hot tunes.

CG: Well, they would have probably played Ragtime Annie, and Over the Waves Waltz, and probably would have used a schottische.

JP: Soldiers Joy.

LR: And Soldiers Joy for a hoedown.

JP: Liberty.

CG: Liberty, they might have played -

?(woman's voice): Old Joe Clark.

CG: Well, I don't know if they'd have played Old Joe Clark or not.

JP: No, I don't think so.

VW: Did they have any contests in the area?

CG: I don't know -

VW: There was a regional contest in Weiser.

LR: There were contests around but they were very localized.

CG: You could have heard the Irish Washerwoman played, I suppose.

FF: Lyman, do you recall any contests?

LR: Just a local contest or two among a group is all. It wasn't something that was open to the public.

FF: I know that last year for our poster here we had a picture of a fellow named Ed Farquer who was from Brinnon, and he won the Olympic Peninsula fiddling championship, it was 1927, and they had a contest, and they had his silver cup down at the museum here. And he played on KOMO radio, it was the only radio in town I guess.

CG: I suppose there's no record of what he used for tunes.

FF: It didn't say what he played, but his daughter was the one who brought the stuff in and I talked to her and she said that he played a lot of schottisches. Now this is what she told me. He played a lot of schottishces because there were a lot of Scandinavians working in the woods, and she said he played a lot of waltzes. And those schottisches and waltzes, and she said then they'd do the Virginia Reel.

CG: Yeah, do the Virginia Reel, but that's usually done to a jig.

FF: So what that tells us I don't know. But it was interesting that - what it brought me to think about was the kind of music that you might have had to play at a dance, because of a certain ethnic group of people that were living in the area. Maybe there were Germans over in the farm country, or there were Dutch or Scandinavian or Yugoslavs or whatever.

CG: I betcha old Alvin Sanderson would know the answer to that question.

JC: What is he, 90 something years old?

CG: He's awful close. He's in his late eighties, I'm sure. Alvin's way up there. But Alvin would know, because of course he played one hell of a sweet Scandinavian fiddle. You know there was nothing that Alvin didn't play that didn't have that smooth Scandinavian roll to it I tried and tried to find but never could. But you'd hear - what's the name of that old tune he used to play -

LR: Blueberry Schottische

CG: But there was one old hoedown, oh, it's on the tip of my tongue, it's got three or four different names.

JC: On the waltz, they got a big spread. But on these others the timings got to be right. Polkas -

CG: When you get older you can't remember nothing.

JC: If you get a polka too fast or too slow, it just kills the dancing. But on a waltz you go a wide spread because you got the different Swedish and German, American waltzes. You can play all that range, see,

CG: Southwest waltzes are played quite slow. You take your Canadian waltzes, you got to step out after them.

JC: Most Canadian tunes you have to move around don't you.

CG: You have to get right after 'em.

JP: When you talking about - like Scandinavian and different nationalities that way - they're entirely different than the true old time fiddling was.

CG: Oh yeah.

JP: I was raised in a Scandinavian locale.

CG: Well, it was old time fiddling to them, just like this stuff's coming out of the Southwest is old time fiddling to Texas. I judged the Certified Contest over at Weiser here about four years ago, and setting next to me was one of the judges, and Wild Bill Lyle's wife. And who was it that got up to play - and - oh boy I can't remember now, but he was a fine fine old time fiddler. And she said "Boy, he's a nice looking old man, but an old time fiddler he ain't". And then someone got up and played Sally Johnson and she said "Now that's old time fiddling." She's a certified Texas judge.

LR: Well, it's old time for them.

CG: Well, yeah. This is it. It's old time to them.

VW: If you listen to Eck Robertson's 1923 Sally Goodin with all those variations.

LR: A lot of people condemn the Texas style fiddling. But to them the old style was what they learned in the old times. And that's what they do.

CG: You've got to take into consideration the region.

LR: Just because we heard it later, doesn't make it new.

JP: No.

CG: Now, to answer Frank's question, I do believe we could call ourselves a melting pot as far as music in the Northwest. For today, we have a blend of just about everything. Especially after the Benny Thomasson years brought in the Southwest style that's almost predominant. Maybe it is predominant now, without a doubt. And even before that we were a melting pot of the Ozark and Canadian type shuffle, and Scandinavian.

JC: He definitely made a big mark on this country around here.

CG: Oh yeah. He made his mark on any part of the world he was in. And so basically our ethnic style of music now - we're just a melting pot because we've got a little bit of everything in here. And everybody plays it.

VW: Would you say that's been true for years?

CG: It's been true for the last 10 or 15 years, that I know of, because it's changed.

VW: What about before that? I mean, would you still say that it was a mixture?

CG: Well, the thing was, the old time fiddling was still Ragtime Annie and Arkansas Traveller, blended in with the Western Swing, back then.

LR: You had two factors that changed the music scene, you had your hard Depression in the thirties and your war years '42 to '52, and that influenced what was going on in the music world as far as local things go.

FF: I wonder if I can ask each of the fiddlers a question that we started out, that you could answer one at a time, maybe starting with you. Say, your earlier recollections of playing regularly for a dance where you were. What would a dance evening consist of? What would be the lineup that you can remember of dances and maybe tunes for the dances, or what styles? In other words, was it all square dances, whatever?

GK: Well, quite a bit of it, for my part, was tunes that was just comin' out at that time, like The Old Spinning Wheel might be a good twostep, or something, you know, like that. Or if you could learn something from somebody. I didn't have too many people to learn from, and I'd have to pick up the tune the best I could.

FF: Now if a person came to a dance that you were playing at, what could they expect for the evening in terms of the kinds of dances that would be done? Would you start out with a slow tune, start with a what?

GK: Usually, like say we'd go up into Joseph Creek Oregon in there, why this old rancher there, he had about eight bunkhouses and he had them full of people, we'd come in by horseback, you know, he gets down there, and he goes out on the floor and he hollers out "Now we'll have a two-step" or "we'll have a foxtrot", "we'll have a waltz", and he announced every tune, everything. So you play what he says. And I could do it.

JC: We used to have a board, and we had what we called a floor manager. His job was to manage the crowd, and then change the tunes, you see. And he would - every so far he'd go about four or five tunes then he'd have a waltz. And what we called a duty dance, you know, maybe somebody'd come with you and have a wife that would walk all over you if you was dancing with her, see. So you didn't play any of your tunes too long, you know what I mean? You'd have a group of two tunes, but you wouldn't play 'em too long. Because that gal might be climbin' your shins all the time. (laughter) You wouldn't step on them, but they'd step on you, boy, and you was glad to get rid of 'em. You know what I mean. But you had to dance with 'em, see.

FF: You'd play like a group of tunes, do two waltzes right in a row, or -

JC: I'd play two waltzes, but different tunes. Same tempo.

VW: And would you do two schottisches in a row, or two polkas?

JC: If I played two schottisches I'd play a run of schottisch and I'd stop and I'd start again.

FF: And a duty dance would come in between the square sets or whatever?

JC: I would play - like any group I would play - now Bob Wills played the same tune twice. I would play a different tune, you know what I mean? I'd play one tune, then I'd play another tune just the same tempo, but a different tune, see.

LR: In the early days, when I was playing up there, we had no amplification.

FF: This was near Lynden?

LR: That was between Lynden and Blaine and Ferndale, the triangle area there.

FF: In what, in Grange halls?

LR: Grange Hall circuit. The caller was a factor. He had to operate without assistance at all sound-wise, and it was a strain on him. So he would generally open the evening, and he was the floor manager, he'd open the evening with a square dance. Then he had three dances to rest. We'd play a waltz, a two-step, and a mixer. Then he'd come back with a square. And that would be the second tip. Then we'd come back with a waltz, and a mixer, and a schottische, and a mazurka, or a three-step, and he got is wind before he started the second set. And that's the way we worked the whole evening long. We were working in with him but he was a factor because his voice was the only thing he had to work with, and we had to favor him if we could. We could play against a outcropping of the stage, and that was the projection that we had for the music. And we had a piano, and the banjo, and stuff that would project itself pretty well. But the human voice, with the people, a lot of feet on that rough floor, it was hard for him to make the people in the far reaches of the hall hear. So consequently he favored himself by having that break in there and that's what governed us in what we played. But the people got used to it, and they liked that pattern of dancing because they got a chance to - some of 'em liked to square dance, some of 'em liked to sit and watch the square dancing, and so you had something for everybody. And that pattern seemed to work real well and until we got sound equipment, that was the format that we followed.

JC: I found out another thing in playing for dancing, you dance fiddlers will agree, you don't let people sit down and get cooled off.

JP: Nosirree!

JC: Now you do your restin' after the dance, you don't do it while you're playing for a dance. If you sit around, smoke a bunch of cigarettes, and getting comfortable, and you won't get up an dance again.

CG: They'll go out and get drunk on you.

JC: The thing to do is to keep 'em sweatin'.

CG: That's why you never got drunk.

JC: Damn right. It poured out of me.

FF: Joe, you played for a lot of different kinds of dancing; you did a lot of foxtrots, and -

JP: That's in later years. In the20's.

FF: But up around the Bellingham area where you played, was that a similar format?

JP: Well it was all the way down. We played in a real permanent band. We played all the way down into California and back up in Union, the well-known Trianon ballroom in Seattle.

FF: More couple dancing than squares?

JP: Oh, it was all foxtrots and slow stand-on-the-floor-and-do-your-necking waltzes. It was the foxtrot era, and rags, of course, good rags. And it had good instrumentation, you know, that's what I loved about it.

FF: What would the instrumentation be that you loved?

JP: Well, I liked it because it was two clarinets and they could played countermelody to my fiddle. We had no amplification. You had to get out there and play.

JC: You had to have a fiddle that'd reach out.

JP: You bet you did. And then we had two sousaphones, and then the slides and trumpets and all that sort of thing. And they'd give you a nice talking background, the trumpets, they'd just chatter behind you. And a nice slide once in a while - you could do a lot of things. I was going to tell you about playing for yourself and not for the crowd. I got up there and played a hot lick chorus one time, all the way through. Oh the people up along on the head of the stage, you know, they just loved to hear that, see. But they couldn't sing the words, and they couldn't dance to it, you see. And when I got - the intermission came, just a couple, two or three dances later, Bill Sherman come down with his clarinet, you know him real well, and he was a taskmaster, boy. He said "Say, you're really hot tonight, ain't ya? But let me tell you, let's do this as we rehearsed it." (laughter) I got blowed off big when he said "you're hot" and then when he said "But let me tell you," he said, "let's do it as we rehearsed it." I was right down where I belonged again.

CG: Your sail come right down around the pole.

JP: Joe Venuti was a great hot lick man, but when he played with Paul Whiteman, and many of those other bands, he's play two hot licks, great runs, but he was always in there with the melody, so you could tell where the melody was. You betcha, he was a crackerjack.

GK: The Charleston come out in about 1930, I think it was.

JP: I was railroading then.

GK: And they were going wild over that for a while, and then the stomp, and there were certain tunes that people were dancing to, you know, that kind of took over in the relatively younger groups.

JC: Another thing I have found that just because a piece of music is written in B flat that don't mean you have to play it there.

JP: No sir.

JC: I tell these guys, play it where you can handle it.

JP: And some tunes you can get a lot more effect for expression and shading.

CG: That's the word you were lookin' for, expression.

JC: Yeah, you can get more expression out of it.

JP: Some waltzes you can make expression and shading and technique in it that you can't if you don't pick another key.

JC: I had a very fine old fiddler tell me - I won't mention names because he's gone now - but he said that when you learn a tune it had to be played in a certain key. And I said," Why do you have to play 'er there, Steve?" And he said "That's where it's written." I said "I don't give a damn. That don't mean nothing."

JP: Not a thing, no.

JC: Play it where you can handle it.

JP: Make it sound the best.

JC: That's right. If you have to get into Asia Minor, put 'er there. [laughter]

FF: One of the other interesting things to me is not just the fiddlers' point of view but we've got a bunch of ladies here that married fiddlers, but I don't know how many of you met at dances or what - it would be interesting to hear what some points of view are about this music, and maybe the view from the other side of the hall, maybe, I don't know, might have any bearing on what we're talking about.

VW: Pauline was on the same side of the hall.

CG: Not at first.

PG: Oh yeah, I sang.

CG: Yeah, we did a little vocal work together. I was playing the fiddle the first time I ever saw her, bless her little heart.

PG: I played music before I met Chuck, though, with my family.

JC: I was fortunate to be like Chuck, married to a good musician and piano player, and we played together for about 45 years, maybe a little more than that. It helps a lot.

CG: Makes it easy. You don't have to get a guitar picker every time go somewhere. All them pianos are hard to haul around.

JC: And half of them are out of tune.

CG: They are when you get there, believe me.

AJ: I'm curious to ask about one of you made an allusion to dances with records. Did this have a real impact on live musicians or had the use of live musicians been interrupted anyway by the war.

JC: Well, here's the deal, a guy a can go out and pay a hundred dollars for cheap outfit that's got a record player, and then they can send down here to someone in Denver and get these records, and I don't know if you get one a month, or two a month, or how you do it, because - He can be a manager of the Safeway store down here, and he can go out on Saturday night and in three hours make himself a hundred dollars. And he can do this four nights a week.

JP: Playing records.

JC: They won't hire a band to play.

CG: The chances if they didn't have them records they wouldn't be out there doing anything to hire live music.

JC: No, they wouldn't hire live music.

CG: I don't think it's putting anybody out of work.

JC: The guy said "you can't play what we dance to", and I said "just who the hell do you think makes your records."

JP: Well, it costs a lot more to hire live musicians than it does to play a record. Way more.

CG: I don't think it ever put any square dance fiddlers out of work, because these people wouldn't be doing it if they didn't have records.

JC: I know that these guys some of 'em were hiring out for these weddings and one thing or another, and they've got all these records and they can play anything you want. And they go for 350 a night. Three hundred and fifty bucks, that's what they're paying. I've got a friend collecting every week.

JP: Isn't that something!

JC: Yeah, he just goes out there and he's got these records and if you want swing he's got that and if you want - whatever you want, he's got it.

FF: Have any of you gotten involved in the revival of interest in dancing, square dancing -

JC: Well, there of course is a racket I'd say that these guys are running in the square dance deal because they come out every week with this new dance, and if you don't go every week, why, you're just that dance behind.

JP: Well, I can tell you an occasion. Phil and Vivian and I and the rest of band, we played for a dance down at Sumner. And we played good old square dance time. And one square dance, and a waltz, and two-step and another square dance, and these - they physically wasn't able to do it. They're used to square dancing to -

JC: Walk around

FF: Square walking.

JP: Square walking, not dancing. They're physically too old to dance that tempo. Oh, they really went to it when we played, oh boy, they thought that was great. But their tongues was hanging out. [laughter]

CG: Yeah, I've played a few where these callers play a patter call, you know, you'd look at him, get her down there a little bit, you know.

JP: I'm Looking Over a Four Leaf Clover is one of them great square dance tunes, now. [sings] And they go walking around like that. If you started playing the Arkansas Traveller or some -

JC: Do you know that what I've decided over these seventy years I've been monkeying around music, that about 80 percent of the people haven't got any music in them.

JP: True. Watch it when they're dancing.

JC: They're not dancing to the music at all.

JP: You play to those good dancers out there. If they like it, the rest of them -

JC: You see them old waltzers come around, they could have had a cup of coffee on their heads.

JP: Beautiful, wasn't it, really beautiful.

JC: Man! Just as smooth as velvet.

CG: Too bad you don't see many any more.

JC: You don't see that; they've got to be jumping up and down, throwing each other across the room or something like that.

CG: Most of them as old as we are if not older.

VW: Frank was talking about I think this other revival of old time dancing to live bands. Like in Seattle there's the Ballard Eagles hall, old time dancing to live music and it's square dancing -

CG: They have a ballroom set up in Olympia too. I haven't got involved in it yet, I've never been asked. I would probably turn them down.

VW: I think it would be really nice if the old time fiddlers got mixed up with that scene.

CG: It would be nice, but I don't think I could last that long.

JC: Looking we'd set up there and beat our legs off.

FF: They sit down now and play.

CG: Yeah, but then again you've lost half of your -

JC: Yeah, you've gotta stand up there. And another thing, you can't play on a level with people. You've got to be above them.

JP: That is certainly true.

JC: To play. But not to give the impression that you are above them, you know what I mean. They're doing you a turn to come and hear you. You're not doing them anything by playing for 'em, see. But you want to leave them with the effect, "Boy, he's coming out here to entertain us guys, and he's a good guy." He'll sign this paper if you want him to, and give them their name, you know. These people are above you, as far as an entertainer is concerned, you know what I mean, just to be there. Four hundred people come and pay $3 to hear you play,

JC: Well, we had some great times over the years. I wouldn't -

CG: I wouldn't trade them for a million bucks.

JP: No.

CG: I don't know if I'd want to go it for 45 cents again.

JC?: I'm telling you.

JP: I rode all over the Western part of North Dakota horseback, played the fiddle, and they'd pass the hat. When I was thirteen - fourteen years old.

JC: That's all you got.

JP: And boy, sometimes, I once played for seven dollars, I'll never forget, I played from 9 in the evening till 6 in the morning. And then I went out and milked the cows. This fellow had some cows to milk, and some cattle to feed, And then we had a big breakfast, we had venison, I remember to eat, and a big meal. And then they wanted to hear some more playin', but I was all in by that time.