Bernice Johnson Reagon

Bernice Johnson Reagon (born 1942) is a world-renowned vocalist, song leader, composer, and historian who knows that singing is not for the faint of heart. A fervent advocate of righteous harmony, both literal and figurative, she has spent a lifetime using the power of vocal music to fight for social justice, from the student sit-ins of the ‘60s to more contemporary struggles against white supremacy. Among her myriad accolades are a MacArthur “genius” grant, the Presidential Medal and Charles E. Frankel Prize, and two Grammy nominations for her work with Sweet Honey in the Rock, which she founded in 1973. Her dedication to preserving and promulgating the vital musical traditions of Black America inspires people of all identities to raise their voices and demand freedom.

A child of the Jim Crow South, Johnson Reagon was born and raised in Dougherty County, Ga., near its seat of Albany, a city with a strong vocal music tradition. Since the Baptist church where her father served as preacher did not have a piano, she grew up attending Sunday services full of a cappella singing, the source of many songs she would later adapt into protest music. She first became active in the civil rights movement as a teenager; in 1959, she joined the local NAACP Youth Council at Albany State College, where she was enrolled in the voice program. The following year, Morehouse College activist Julian Bond contacted the group and encouraged them to join the nationwide sit-in movement, and the students agreed. Although she admits she was initially apprehensive about civil disobedience, Johnson Reagon later said that you have to push past your fear “or you will never meet yourself.”

In 1961, Johnson Reagon helped to organize a local demonstration protesting the arrest of two Black activists who attempted to buy interstate bus tickets from a white-only counter. When she was asked to lead a song during the protest, she drew on her extensive repertoire of sacred music to spontaneously change “Trouble in the Air” to “Freedom in the Air,” and scores of voices joined in. The leaders of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee were impressed by her passion, her talent, and her intuitive sense of movement-building through song. Executive Director James Forman said she sang “with an urgency and a pain that brought out a sense of intense renewal and commitment of liberation.” Her college, on the other hand, suspended her after she was arrested for her activism.

Albany State College’s loss was SNCC’s gain. When Pete Seeger suggested that a traveling vocal group could build support for the civil rights movement and raise funds for the Committee’s voter registration work, Johnson Reagon was an obvious choice for a founding member. Against her parents’ wishes, she walked away from a full scholarship at Spelman College after just one semester to join the SNCC Freedom Singers with Charles Neblett, her Albany classmate Rutha Harris, and her future husband Cordell Reagon. The group traveled the country with their protest songs, braving treacherous journeys through hostile towns to bridge cultural divides and sustain spirits. They even performed at the March on Washington in 1963.

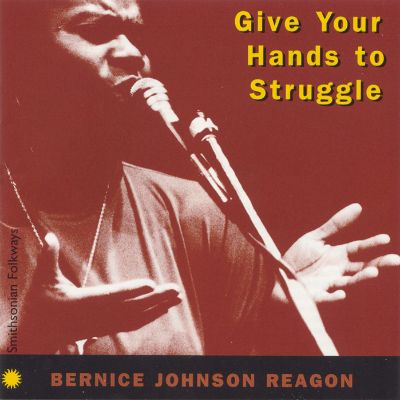

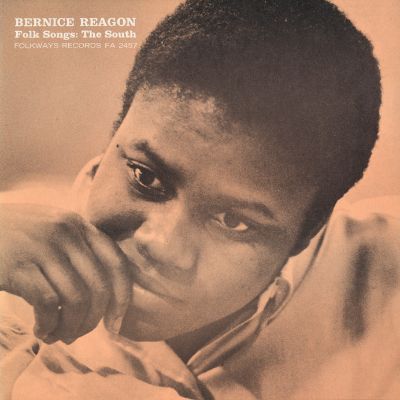

Johnson Reagon left the Freedom Singers when her daughter and future collaborator Toshi was born in 1964, but her musical career was just getting started. During the ‘60s and ‘70s, she recorded several solo albums, including Folk Songs: The South (released by Folkways in 1965) and Give Your Hands to Struggle (released by Paredon Records in 1975 and re-released by Folkways in 1997). She toured internationally, performed alongside activist and politician Fannie Lou Hamer at the Newport Folk Festival, and became a festival organizer in her own right. In 1968, two women approached Johnson Reagon after a concert and told her they wanted to sing with her. A song leader first and foremost, she responded by founding the Harambee Singers, a women’s a cappella group rooted in the Black Arts and Black Power Movements.

In 1973, after the Harambee Singers parted ways, Johnson Reagon founded another Black women’s a cappella ensemble: the legendary Sweet Honey in the Rock, formed to share the social and political power of Black American vocal music with a new generation. The group of four to six singers draws from field hollers, jazz tunes, spirituals, rap music, and more for their still-growing discography, which now spans six decades. Alongside music of the civil rights movement, they perform songs speaking to other pressing political issues, such as climate change and immigration. Johnson Reagon produced the majority of Sweet Honey in the Rock’s albums before retiring from the group in 2004.

The group’s musical explorations were informed by her pioneering research into the performance practice of Black American traditions. After returning to Spelman in the late ‘60s to complete her undergraduate degree, Johnson Reagon earned a Ph.D. in American History from Howard University in 1975. For the next few decades, she worked as a cultural historian in various branches of the Smithsonian. Her accomplishments with the Smithsonian include founding the Institution’s Program in Black American Culture, producing the Voices of the Civil Rights Movement set with Smithsonian Folkways, and hosting the award-winning radio series Wade in the Water: African American Sacred Music Traditions, a collaboration with National Public Radio. A prolific academic author, Johnson Reagon has also served as Professor of Fine Arts at Spelman, her alma mater, and as a music consultant and composer for numerous radio and film projects. Today, she is a Curator Emeritus at the National Museum of American History and Professor Emeritus of History at American University, where she taught from 1993 to 2003.

Bernice Johnson Reagon stands alone in her multidimensional commitment to fusing the musical history of Black America with ongoing struggles for civil rights. She has been recognized as an outstanding performer-scholar with countless awards, more than a dozen honorary degrees, and a televised visit to the White House under President Barack Obama. She continues to compose across genres, traditions, and media, relying at every turn on a lesson she learned from the congregational music of her father’s church: The power of a collective is strongest when each individual voice asserts its rightful presence. “It’s like claiming your space,” Johnson Reagon once said. “We had been too long out of the light. It was our time. It still is.”