Dewey Balfa

An impassioned ambassador for Cajun music and culture, fiddler and singer Dewey Balfa (1927-1992) was a driving force in the revival of traditional Cajun music. Together with his brothers Will, Rodney, Harry, and Burkeman, and later his nephew Tony and daughter Christine, Balfa introduced the vibrant sound of Cajun music to countless people around the world and used his role as a musical ambassador to reawaken a deep and abiding sense of pride in Cajun music amongst his fellow Cajuns.

Dewey was one of nine children born into a musical family in Grand Louis, Louisiana, a small farm town in rural Louisiana not far from the slightly larger town of Mamou, 125 miles northwest of the great port city of New Orleans. In terms of culture, Louisiana is one of America's wealthiest states, and the Balfa family had inherited the rich legacy of songs, tunes, tales, and traditions of Louisiana's French-speaking Cajun community.

The history of how the Cajuns came to Louisiana is long and complex. It begins with immigrants from western France who settle the Acadia or "Cadie" region of New France in the 16th and early 17th centuries. After Acadia came under British rule in 1755, its new owners renamed the colony Nova Scotia and forced many of the French-speaking Acadians to leave. Like many others, the Balfa family eventually made their way down America's eastern seaboard to the Spanish colony of Louisiana, where they were welcomed and able to join an already established French community. As the Acadians adapted their culture to Louisiana's prairies and bayous, and as they interacted with new neighbors of Spanish, Celtic, Native American, and African origins, a distinctive "Cadien" or "Cajun" culture evolved.

Dewey Balfa's father Charles, a share-cropper, was a major influence in his life, sharing his love for the old Cajun songs and tunes with his children at a time when the Cajun language and traditions were looked down upon by their English-speaking neighbors. Inspired by his father, Dewey grew up during the 1930s and '40s making music in his home, for community events, and at local dance halls. In the mid-1940s, as part of the Musical Brothers with his siblings Will, Harry, Rodney, and Burkeman, he frequently played for eight or more community dances a week, while at the same time holding down a succession of full-time day jobs. (In the course of his career, Dewey worked as a farmer, drove a bread truck and a school bus, and sold cars, insurance, and furniture.) Dewey's strong sense of tradition was based on a deep musical heritage going back generations in his family. "My father, grandfather, great-grandfather, they all played the fiddle," he told an interviewer, "and you see, through my music, I feel they are still alive."

Cajun music was first recorded in the late 1920s—Joseph Falcon and Cleoma Breaux's 1928 "Allons a Lafayette" is believed to be the first genuine Cajun music recorded. Throughout the 1930s and '40s recordings by such Cajun artists as Amede Ardoin, Dennis McGee, Lawrence Walker and Nathan Abshire, and Mayuse LaFleur sold well regionally, although the style was largely unknown outside Louisiana.

Despite its long history and its attractiveness as a genre, by the 1950s Cajun music, as well as Cajun culture in general, were in serious decline. In the post-WWII era, Americans were urged to discard regional cultures for a more modern, albeit homogenized, national one. In an era that saw the rise of rock and roll, many Cajuns were embarrassed by the regional French they spoke and the old-fashioned "chanky-chank" music still being played in their communities.

It's a rare thing to be able to point to one event as changing the course of a culture's history, but in the case of Cajun culture, Dewey Balfa's participation in the 1964 Newport Folk Festival was pivotal. That year, in the midst of a revival of American public interest in folk and regional culture, folklorist and traditional music promoter Ralph Rinzler (who later went on to found the Smithsonian Folklife Festival) invited a Cajun group to perform at the prestigious Newport Folk Festival. Dewey actually went to the Rhode Island festival as a guitarist—a last minute replacement in an ensemble that included the great Cajun accordionists Gladius Thibodeaux and Louis "Venesse" Lejeune. To their amazement, rather than laughing at them, the largely urban audience of 17, 000 went wild. As Dewey recalled many years later:

"I had played in house dances, family gatherings, maybe a dance hall where you might have seen as many as 200 people at once. In fact, I doubt I had ever seen 200 people at once. And in Newport, there were 17,000. Seventeen thousand people who wouldn't let us get off stage."

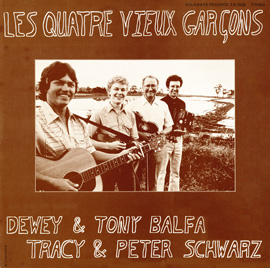

With renewed pride in Cajun culture, as well as a sense of its commercial potential outside Louisiana, Dewey returned to Louisiana and in 1965, with his brothers Will, Rodney, and Harry on fiddles, guitars, and triangle and Hadley Fonetnot on accordion, established the Balfa Brothers Band. The group played the 1967 Newport Folk Festival, and again their Cajun music received a tremendous response from a sophisticated, non-Cajun audience.

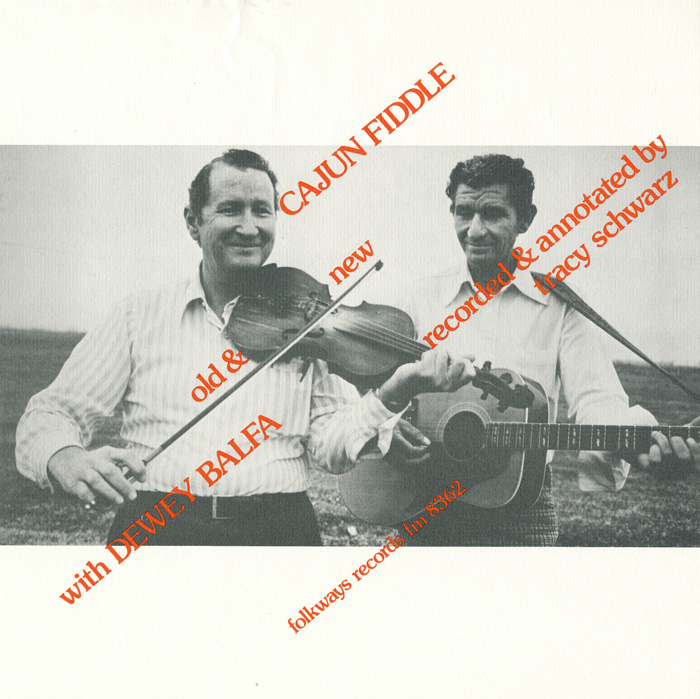

In the decades that followed, Dewey's experiences in Newport motivated him to become an advocate for Cajun culture: "My culture is not better than anyone else's culture. My people were no better than anyone else. And yet, I will not accept it was a second-class culture." As a member of the Balfa Brothers and as a soloist, he participated in numerous Smithsonian Folklife Festivals in Washington, D. C., and at scores of other festivals and public events across the United States and around the world, bringing Cajun music and his love for Cajun music to millions of people. He worked closely with the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) to increase studies of the French language in the state's schools; he helped to launch the Tribute to Cajun Festival in Louisiana in 1974. He recorded on a variety of labels, including albums for Smithsonian Folkways, two of which are instructional albums on playing the Cajun fiddle.

Dewey's career suffered a major setback in 1979 when his brothers Will and Rodney were killed in an automobile accident and then with the death of his wife in 1980. Gradually, he returned to the concert circuit, and in the years that followed he became increasingly influential as a spokesperson, a teacher, and an inspiration to a new generation of Cajun musicians, including artists such as Michael Doucet, and Marc Savoy, who themselves went on become icons to the next generation of Cajun musicians.

Although Dewey believed that "a culture is preserved one generation at a time," he was open minded and supportive of the innovations taking place during the 1970s and '80s as Cajun music went from a little-known regional style to an internationally recognized and imitated musical phenomenon. "A culture is like a whole tree." He believed "You have to water the roots to keep the tree alive, but at the same time, you can't go cutting off the branches every time it tries to grow."

Dewey's importance as a cultural leader was officially recognized by the United States in 1982 when he received a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts—America's highest award for excellence and achievement in the traditional arts.

For more information on Cajun music:

Cajun and Creole Music Makers: Musiciens Cadiens Et Creoles by Barry Jean Ancelet, Elemore Morgan, Ralph Rinzler, University Press of Mississippi (September 1, 1999)

Cajun Music and Zydeco by Philip Gould, Louisiana State University Press (September 1, 1992)

Cajun Music a Reflection of the People (Cajun Music, 1) by Ann A. Savoy, Bluebird Pr (June 1, 1984)