Elizabeth Cotten

-

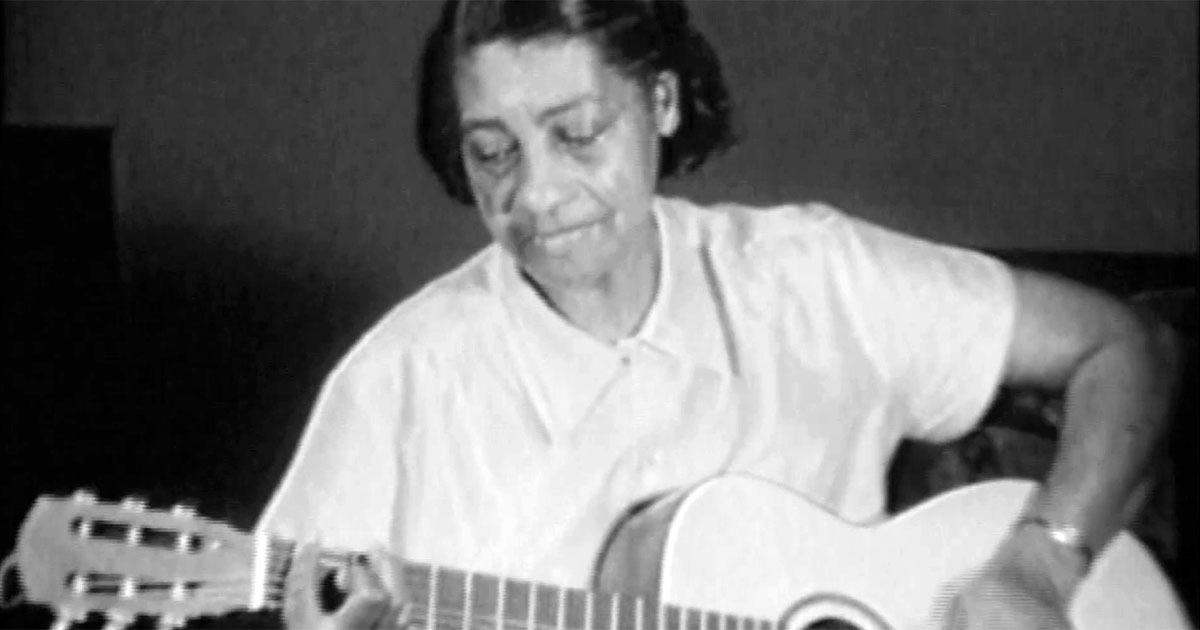

Elizabeth Cotten, Washington, D.C. in 1960Photograph by John Cohen

-

Elizabeth Cotten performs at the 1968 Newport Folk FestivalPhotograph by Diana Davies. Courtesy of the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, Smithsonian Institution

Elizabeth "Libba" Cotten (1895-1987), best known for her timeless song "Freight Train," built her musical legacy on a firm foundation of late 19th- and early 20th-century African-American instrumental traditions. Through her songwriting, her quietly commanding personality, and her unique left-handed guitar and banjo styles, she inspired and influenced generations of younger artists. In 1984 Cotten was declared a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment for the Arts and was later recognized by the Smithsonian Institution as a "living treasure." She received a Grammy Award in 1985 when she was ninety, almost eighty years after she first began composing her own works.

Born in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Libba Cotten taught herself how to play the banjo and guitar at an early age. Although forbidden to do so, she often borrowed her brother's instruments when he was away, reversing the banjo and guitar to make them easier to play left-handed. Eventually she saved up the $3.75 required to purchase a Stella guitar from a local dry-goods store. Cotten immediately began to develop a unique guitar style characterized by simple figures played on the bass strings in counterpoint to a melody played on the treble strings, a method that later became widely known as "Cotten style." She fretted the strings with her right hand and picked with her left, the reverse of the usual method. Moreover, she picked the bass strings with her fingers and the treble (melody strings) with her thumb, creating an almost inimitable sound.

Libba married Frank Cotten when she was 15 (not a particularly early age in that era) and had one child, Lily. As Libba became immersed in family life, she spent more time at church, where she was counseled to give up her "worldly" guitar music. It wasn't until many years later that Cotten, due largely to a fortunate chance encounter, was able to build her immense talent into a professional music career. While working at a department store in Washington, D.C., Libba found and returned a very young and lost Peggy Seeger to her mother, Ruth Crawford Seeger. A month later, Cotten began work in the household of the famous folk-singing Seeger family.

The Seeger home was an amazing place for Libba to have landed entirely by accident. Ruth Crawford Seeger was a noted composer and music teacher while her husband, Charles, pioneered the field of ethnomusicology. A few years passed before Peggy discovered Cotten playing the family's gut-stringed guitar. Libba apologized for playing the instrument without asking, but Peggy was astonished by what she heard. Eventually the Seegers came to know Libba's instrumental virtuosity and the wealth of her repertoire.

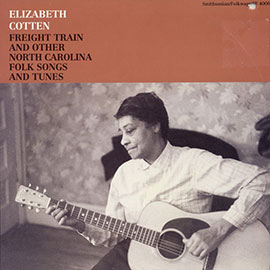

Thanks largely to Mike Seeger's early recordings of her work, Elizabeth Cotten soon found herself giving small concerts in the homes of congressmen and senators, including that of John F. Kennedy. By 1958, at the age of sixty-two, Libba had recorded her first album, Elizabeth Cotten: Negro Folk Songs and Tunes (Folkways 1957, now reissued as Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs, Smithsonian Folkways 1989). Meticulously recorded by Mike Seeger, this was one of the few authentic folk-music albums available by the early 1960s, and certainly one of the most influential. In addition to the now well-recorded tune "Freight Train," penned by Cotten when she was only eleven or twelve, the album provided accessible examples of some of the "open" tunings used in American folk guitar. She played two distinct styles on the banjo and four on the guitar, including her single-string melody picking "Freight Train" style, an adaptation of Southeastern country ragtime picking.

As her music became a staple of the folk revival of the 1960s, Elizabeth Cotten began to tour throughout North America. Among her performances were the Newport Folk Festival, the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the University of Chicago Folk Festival, and the Smithsonian Festival. Her career generated much media attention and many awards, including the National Folk 1972 Burl Ives Award for her contribution to American folk music. The city of Syracuse, New York, where she spent the last years of her life, honored her in 1983 by naming a small park in her honor: the Elizabeth Cotten Grove. An equally important honor was her inclusion in the book I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America, by Brian Lanker, which put her in the company of Rosa Parks, Marian Anderson, and Oprah Winfrey.

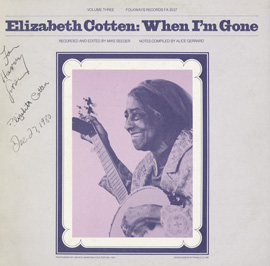

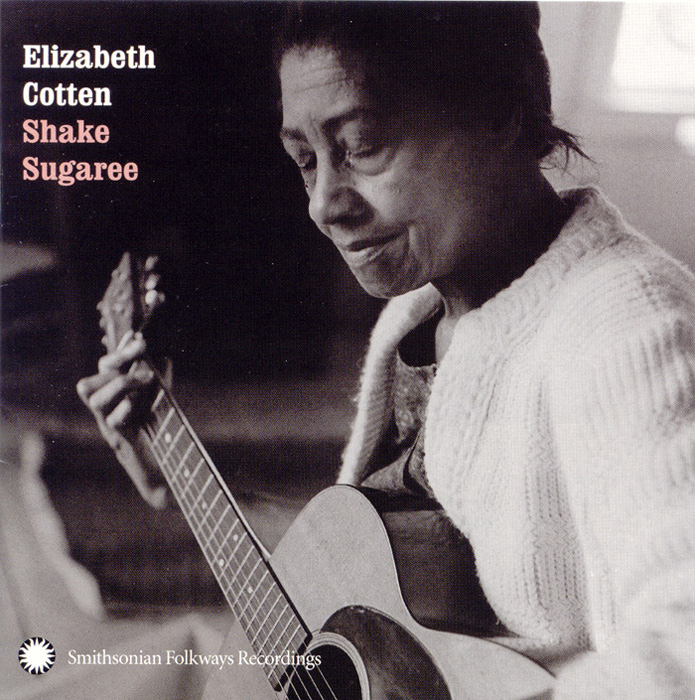

Cotten's later CDs, Shake Sugaree (Folkways, 1967), When I'm Gone (Folkways, 1979), and Elizabeth Cotten Live (Arhoolie 1089), continued to win critical acclaim. Elizabeth Cotten Live was awarded a Grammy for the Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording in 1985.

Elizabeth Cotten continued to tour and perform right up to the end of her life. Her last concert was one that folk legend Odetta put together for her in New York City in the spring of 1987, shortly before her death. Cotten's legacy lives on not only in her own recordings but also in the many artists who continue to play her work. The Grateful Dead produced several renditions of "Oh, Babe, It Ain't No Lie," Bob Dylan covered the ever-popular "Shake Sugaree," and "Freight Train" continues as a well-loved and recorded tune played by Mike Seeger, Taj Mahal, and Peter, Paul, and Mary, to name a few. Libba's recordings, concert tours, media acclaim, and major awards are a testament to her genius, but the true measure of her legacy lies with the tens of thousands of guitarists who cherish her songs as a favorite part of their repertoires, preserving and keeping alive her unique musical style.