John Jackson

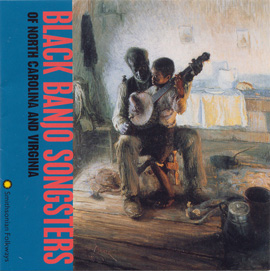

Bluesman and songster John Jackson was born in the rural Blue Ridge Mountain foothill town of Woodville, Virginia, in 1924. Playing both banjo and guitar, he entertained at gatherings and house parties in his native Rappahannock County as a youth. Jackson had the most delightful, molasses-sweet rural Virginia accent and was able to add a couple of syllables to every word he spoke. He was one of the great practitioners of the Piedmont blues (formerly East Coast blues) guitar style, which relies on finger picking and melody as opposed to the more percussive nature of Delta blues. He heard a great deal of music on 78 rpm discs by artists such as Jimmie Rodgers, Blind Blake, and Mississippi John Hurt, and he learned to play many of the tunes. Jackson could and would play everything from straight blues to covers of Tom T. Hall songs.

A particularly violent episode Jackson witnessed at a country picnic as a young man convinced him to give up entertaining. He moved to Fairfax Station, Virginia, and worked as a gravedigger for most of the rest of his life. But a chance meeting in the 1960s changed things for Jackson. He was picking a guitar in the back room of a Fairfax gas station, teaching one of the employees to play, when folklorist Chuck Perdue stopped in to pay for his gas. He was astounded at his discovery and convinced Jackson to come with him to see Mississippi John Hurt at an upcoming Washington engagement. Jackson was skeptical—of course Hurt must be dead, he thought. However, he went, and needless to say was surprised to see Hurt in the flesh. Jackson then resumed playing for the public.

Hearing him at a show, Arhoolie Records founder Chris Strachwitz was rumored to have shouted out, "I must record that man!" Jackson made three records for Arhoolie and then two more for Rounder in the late 1970s to early 1980s. One final recording was released by Alligator in 1999. Of all of the great 20th-century bluesmen, John Jackson made far too few recordings than befitted his talent.

He toured the world, playing festival after festival. He performed at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival more than anyone else in its history, appearing fourteen times. Living near Washington, D.C., he was the Festival's pinch hitter, filling in when others could not make it. He received the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1996. In his later years, due to the tireless work of his friend and manager, Trish Byerly, Jackson continued to perform frequently right up to the end. I remember seeing him at a party three months before he died. Jackson did not know he was sick and was his usual happy, agreeable self, kidding around with the children. He died of cancer in early 2002. He is sorely missed.

—Jeff Place, 2008

References

I knew John for twenty years, and the anecdotes here come from having heard the man himself tell them.