-

Blog\SFW40241_Cover_3000.jpg

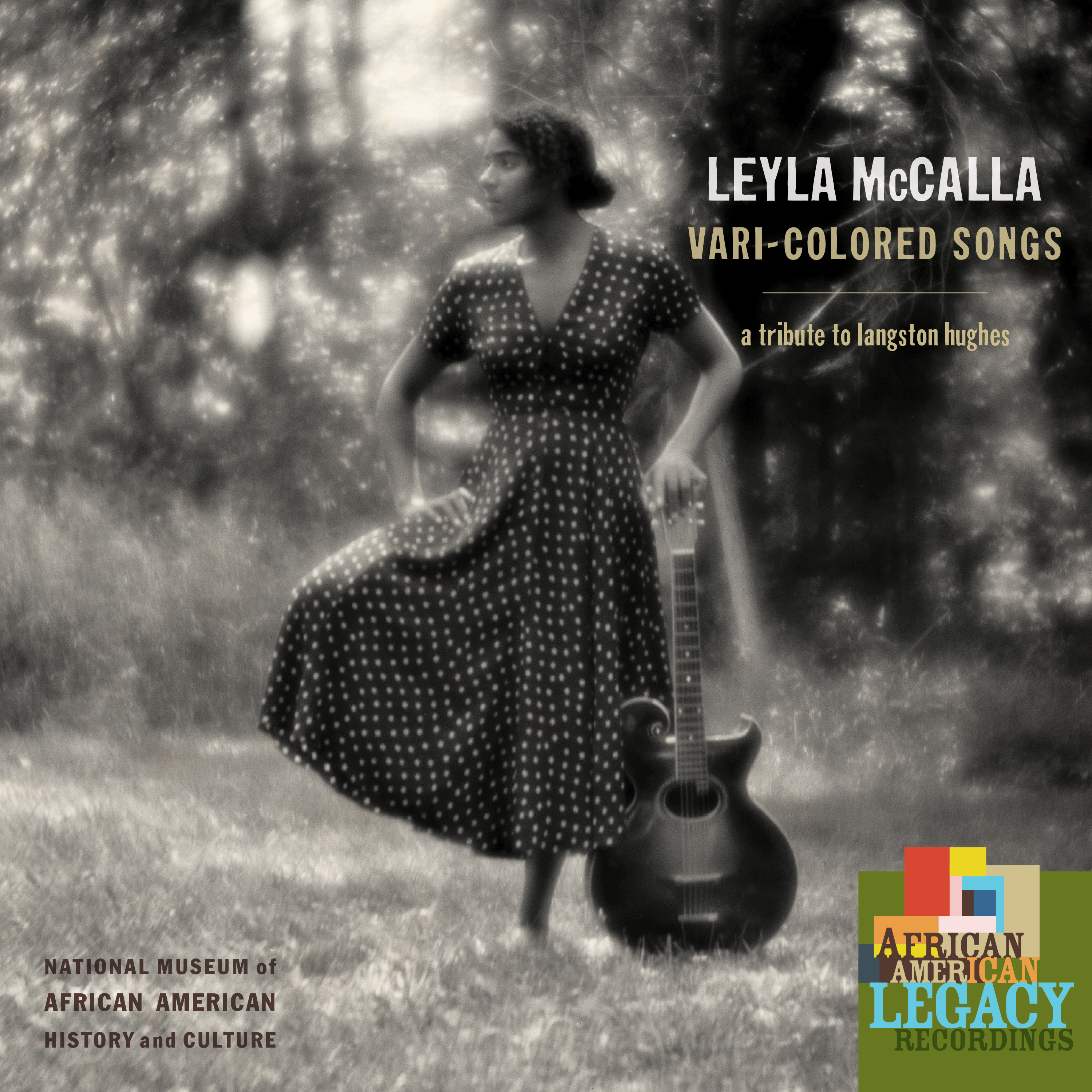

Leyla McCalla Reissues Her Poignant Debut 'Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes'

Celebrated bilingual multi-instrumentalist, cellist and singer Leyla McCalla has announced the reissue of her debut album, 2014’s Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes, out October 16 on CD, LP, and digital formats. Of this collection of her musical settings of poems by Langston Hughes alongside original compositions and traditional Haitian folk songs, McCalla says, “All of these songs are manifestos of my life as a Black, Haitian-American woman and the daughter of Haitian immigrants, and an homage to the humanity and creative spirit of Langston Hughes.”

McCalla first read Hughes as a teenager, when her father gave her a copy of the poet’s Selected Works. But it wasn’t until years later, following her conservatory training and her time playing with the Carolina Chocolate Drops, that she connected with his poems on a musical level. While reading Hughes’ “The Vari-Colored Song,” she was struck by the power of his words — their natural rhythm, the strong imagery, their sense of melody — and found herself setting the poem to music, giving it the title “Heart of Gold.”

Of course, Langston Hughes’ musicality is no accident. As a young poet in New York, he would regularly write while he was in clubs, soaking in the sounds of blues and jazz, and allowing their rhythms and lingo to permeate his writing — leading to the foundation of jazz poetry. He would also be influential in the Harlem Renaissance, and years later, would collaborate with Charles Mingus. For Hughes, Black music wasn’t merely amusement; it was a poetic, a set of coherent artistic choices made for very specific reasons. As McCalla writes in Vari-Colored Songs’ liner notes, he “aimed to legitimize Black vernacular by celebrating its nuances and expressions.” As Vari-Colored Songs shows, the pull of his words accomplishes the same task, “legitimizing” Black rhythm, too.

Composing in her New Orleans home nearly 100 years after Hughes published his first poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1921), McCalla sensed that his words were more urgent than ever. She was also drawn to the folk music of Haiti, where her parents were both born, and to the reaction many had to the 1804 establishment of the “first Black Republic.” After the island gained its independence in the world’s first successful revolt of enslaved people, the population of the Louisiana Territory doubled with emigrants from the erstwhile Saint-Domingue. Hughes, she writes, would certainly have been aware of the incredible power of Blackness this represented: the power to strike fear in the heart of colonizers. Indeed, Hughes translated Haitian author Jacques Roumain, co-wrote a children’s book about the island, authored the play The Emperor of Haiti, and worked on the libretto for William Grant Still’s opera Troubled Island.

McCalla has shared the powerful “Song for a Dark Girl,” based around words written by Hughes in 1927. The poem describes the heartbreak of a lynching. Of the piece, McCalla says, “Fast forward nearly a century after Hughes wrote these words, to the week of George Floyd’s murder; Black men were found hanging from trees in the United States. Their deaths were quickly ruled suicides. Numerous Black bodies have been killed by the police since the protests that brought the Black Lives Matter movement into our mainstream consciousness. What becomes evident here is that history is not the past. History is a living, ever present part of life. In light of the COVID-19 crisis, at such an uneasy time in our history, we need to be reminded that our past will haunt us if we are not willing to look at it. Our failure to care for each other is literally killing us.

“I can see clearly now how acutely Hughes’ work reflects the harm imposed by the white supremacist American paradigm. His work — which spans all genres of writing — celebrates Black culture and Black contributions to American life, countering the chronic dismissal of Black lives, Black feelings and Black thought. To be re-releasing this collection of songs to a wider audience, through the graces of Smithsonian Folkways, at such a critical time in both world and American history, my intention is that these songs will help us to see ourselves again — our tragedies, our humor, our potential and our humanity.”

For McCalla and her collaborators — who include Rhiannon Giddens, Luke Winslow King, Hubby Jenkins, Yah Supreme and more — the combination of Hughes’ early-20th-century poetry and the traditional music of Haiti proves a natural match. She masterfully plucks out determined rhythms with the heavy grace of Thelonious Monk on “Heart of Gold” and makes her cello growl in “As I Grow Older.” The chorus of “Manman Mwen,” which she sings in Haitian Kreyòl, shimmers when she and Giddens join voices in harmony. She accents the humor of Hughes’ blues “Too Blue” and strums thunder in the Haitian “Latibonit.” Much of the music here finds its most familiar antecedent in the traditional sounds of New Orleans — a testament both to that city’s impact on the jazz Hughes was listening to in New York and the profound influence of Haitian culture on the Crescent City. In this way, Vari-Colored Songs suggests, American culture is impossible to conceive of without Haiti.

Vari-Colored Songs had its original, limited release in 2014, and is being presented here anew along with a previously unheard song, “As I Grew Older / Dreamer.” Upon its initial release, Vari-Colored Songs was named the Album of the Year by the London Sunday Times and Songlines, and it received high praise from the Washington Post and the New York Times, who lauded its “weighty thoughts handled with the lightest touch imaginable.” “Re-releasing these songs at such an uncertain time in our global history brings to mind all that has come before us,” she says. “The wisdom and truth that Langston Hughes continues to provide us through his prolific output inspires us to celebrate the assumedly mundane and stigmatized parts of our society.”

Leyla McCalla Reissues Her Poignant Debut 'Vari-Colored Songs: A Tribute to Langston Hughes' | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings