Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard

Before Hazel Dickens & Alice Gerrard, it was incredibly rare to see women fronting a bluegrass band. A myriad of artists in bluegrass, country, and beyond, such as Emmylou Harris, the Judds, Alison Krauss, Laurie Lewis, and even Bratmobile’s Allison Wolfe, have credited the pair as an inspiration. Admired by Bob Dylan and other musical giants, they played alongside the likes of David Grisman, Ralph Rinzler, Elizabeth Cotten, Chubby Wise and Lamar Grier.

The pair embodied the quintessential “high lonesome sound,” a term coined in 1962 by photographer and New Lost City Ramblers co-founder John Cohen to describe the edgy, wailing vocals characteristic of bluegrass music. This sound, attributed to Bill Monroe and Roscoe Holcomb, is often marked by a haunting depth that is both modern and ancient, and has long since captivated listeners as the singer pours out hard truths about the world. Historically, bluegrass singing requires men to lean into their highest vocal register. Cohen himself suggests the “intriguing possibility that the high lonesome sound...aspires to a female vocal range.” When Hazel and Alice sang together, the chemistry of their voices was breathtaking, Gerrard’s round and hollering birdsong anchored by Dickens’ inimitable and piercing tenor.

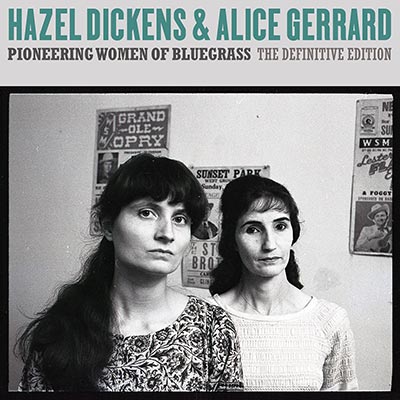

On the surface, the two formed an unlikely partnership: Dickens, a hardworking country girl whose formal education ended after seventh grade, and Gerrard, a younger, free-spirited college dropout from an urban, West Coast family. What they shared, above all, was their zeal for the music and their boldness as women to go out and play it. “The music was our passion,” writes Gerrard in the liner notes of Pioneering Women in 1996. “It was all we wanted to do. We hardly went to movies, and had no TV. We were learning all the time, sometimes traveling for hundreds of miles to see our favorite bluegrass entertainers. And if we weren’t doing that, we were making music ourselves.”

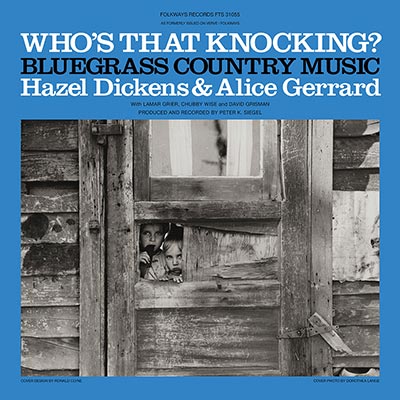

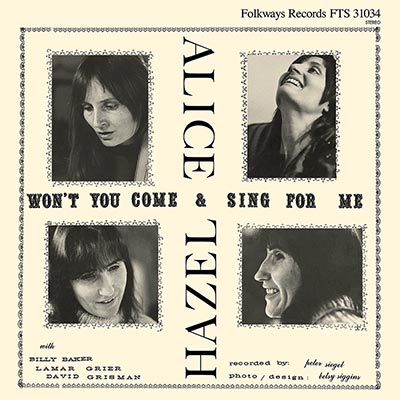

Hazel & Alice began playing together in the bluegrass and old-time music scene in and around the bars and house parties of Baltimore and Washington, DC, in the mid-to-late 1950s. It was not until 1964 that they were approached by David Grisman and Peter Siegel, who arranged for them to audition for Moses Asch. Over the next decade, they recorded four albums, two of them with Folkways Records and two with Rounder Records, before continuing to release music separately. Their debut in 1965, Who’s That Knocking? (And Other Bluegrass Music), was recorded in the First Unitarian Church in Washington, DC, with accompaniment from Grisman, Chubby Wise, and Lamar Grier. Not long after, they recorded their second album, Won’t You Come and Sing For Me?, with Billy Baker on the fiddle and Fred Weisz and Mike Seeger on one track, but it was not released until eight years later in 1973.

Though much of their repertoire celebrated older, traditional-style songs, their music became more politicized throughout their careers as they wrote about social injustices. Dickens once explained that she “didn’t have to work in a factory to see how badly women were treated. Playing in bluegrass, a male-dominated form of music, was enough.” She channeled her feelings into songs like “Don’t Put Her Down You Helped Put Her There” as well as “Black Lung,” inspired by the death of her brother from pneumoconiosis—a song that was later used in the Academy Award–winning documentary, Harlan County USA, about a Kentucky coal strike. Likewise, Gerrard wrote “Beaufort County Jail” about Jo Ann Little, a Black woman charged with murder for defending herself against a white male who tried to sexually assault her. In the late 60s, Dickens and Gerrard participated in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project run by civil rights activists Bernice Johnson Reagon and Anne Romaine. The tour was a racially integrated effort to speak to the struggles of the working class and unify over a shared reverence for tradition. Consequently, Dickens’ and Gerrard’s music spoke to a remarkably diverse audience, from labor unions to southern old-timers to New York feminists.

Born in West Virginia coal country, Dickens grew up with ten siblings in a poor mining community. Her exposure to music began early, partly from singing in the Primitive Baptist church, but mostly from her father’s fondness for the banjo. A drop-thumb player in his youth, he had the radio on constantly. They listened to traditional country and folk music like the Carter Family and weekly broadcasts from the Grand Ole Opry, and Dickens took to memorizing songs that would later influence her own writing.

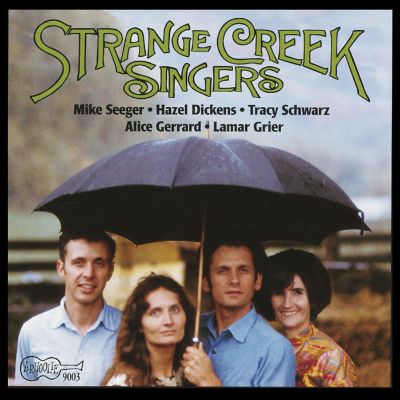

As the coal industry became increasingly mechanized, Dickens and many of her siblings moved to Baltimore looking for opportunity. The city was a hotbed for cultural and political exchange as working-class transplants from the Virginias and Carolinas merged with middle-class, college-educated people. It was in this convergence that the burgeoning old-time and bluegrass movement flourished. Dickens and her brothers played constantly. Eventually she was introduced to Mike Seeger, who worked with her brother Robert Dickens. Seeger then introduced her to Gerrard.

At the time, Gerrard was still an undergrad at Antioch College in Ohio, and had been working at the school’s co-op in Washington, DC. While Dickens grew up around the music, Gerrard’s parents were classical musicians, and she wasn’t exposed to the folk revival or country music until she got to college. There she began playing with peers (one of whom was Jeremy Foster, her first husband) who exposed her to old-time tunes like the ones on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music.

Though she wasn’t raised around the music, Gerrard’s deep connection to it is motivated by a unique combination of her spirit as a musician and documentarian. She once said, “When you listen to real traditional music you have such a sense of this connectedness to a person’s life. It’s like it comes out of the earth.” Because she played music and organized events with the folks she met, she was seen less as a fieldworker and more as part of the community. She was always taking photographs at festivals, and she worked with Les Blank on a documentary about the fiddler Tommy Jarrell. When she moved to Galax, Virginia, in the 80s, she and her friend Andy Cahan received a grant from the Virginia Arts Commission for a recording and photography project with the old-time musicians in the area. The conversations and collaborations that came out of that experience inspired her to start the magazine The Old-Time Herald, which is still active today.

In 1996, Folkways released Pioneering Women of Bluegrass, a 26-song compilation of the two previously released Hazel & Alice albums. In 2022, Folkways reissued those first two albums along with a new version of Pioneering Women of Bluegrass: The Definitive Edition, which includes an additional track. These new releases came just over ten years since Dickens passed away in 2011 in Washington, DC, from complications of pneumonia. Her presence in local music is sorely missed; from 1969 onward, she appeared at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival more than fifteen times, including a performance with Gerrard in 2010 during a Hazel & Alice reunion. Gerrard currently lives in Durham, North Carolina, and still tours regularly. She performed at the 2022 Folklife Festival on the National Mall.