Mary Lou Williams

The music poured from the piano. On a large platform inside the oval mahogany bar at New York’s Hickory House, the last surviving establishment offering jazz on West 52nd Street, “Swing Street,” an authoritative African-American woman in early middle age sat at the piano, eyes mostly closed, her face registering every nuance in the music she was creating, back straight, her hands lying flat as they moved on the keys. She was wearing a royal blue chiffon gown of cocktail length, softly gathered at the shoulders. Her arms were bare. She had a beautiful throat and neck, good collarbones, and a dark brown face rising up from a strong chin to high cheekbones. Her mouth was well shaped and soft, and at times broke into a brief radiant smile when she achieved a particular musical passage. The smile never interfered with the concentration. There was nothing theatrical about her. You simply knew that you were in the presence of someone of the highest magnitude. Her name was Mary Lou Williams.

The emotional experience of the music and the woman herself was so strong that my life at once took on a permanent new direction. There was no confusion or doubt in me, and although I could not possibly have known the full consequences of that night’s depth of feeling, I had found my purpose. I was finally at home.

At the end of her set, she descended from the platform and exited as the bartender raised the flap to let her through. Her two accompanists repaired to a booth along the back wall of the room, and she sat at a small square table set at an angle slightly back from the traffic around the bar.

I slid off the bar stool and walked nervously toward her and told her my name. She asked me, “Are you a priest?” I told her, “No, I’m a Jesuit seminarian and I will be a priest.” She was subdued—almost mute. I had been especially moved by one piece she played and asked her what her third-to-last number was. She replied, “Oh, that was just a blues.”

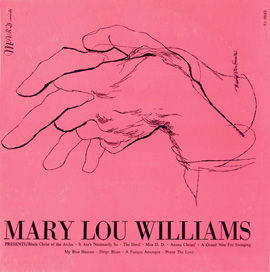

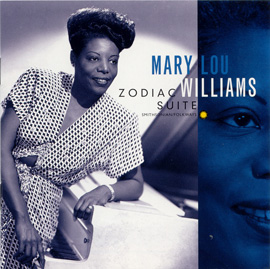

When I asked about her record, she gave me a large square manila envelope. I removed the contents. It contained her LP, which had a pen and ink drawing of praying hands on a pink background and large black letters proclaiming MARY LOU WILLIAMS presents. A second, much smaller recording, showing a chiaroscuro black-and-white photograph of Mary Lou Williams was called Music for the Soul and contained selections from the LP.

I was too shy to ask her to sign the records, but I did ask her how I might reach her. She gave me a tiny card. On one side was her name, address, and telephone number; on the other, the address of the Bel Canto Thrift Shop. Though Loyola Seminary was north of New York City, we had a tie-line, making all calls to Harlem local. From then on, I was on the phone to her every day.

Mary Lou Williams lived and played through all the eras in the history of jazz: the spirituals, ragtime, the blues, Kansas City swing, boogie-woogie, bop or modern, and musics beyond—playing the new music of each era, a claim that is difficult to dispute. She had perfect pitch, was entirely self-taught (her mother had never allowed a teacher to interfere with her), and often as a child spent twelve hours at a stretch at the piano.

She was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on May 8, 1910. Her mother was Virginia Riser; her father was Joseph Scruggs. As part of the great black migration, Virginia traveled north, somewhere between 1914 and 1916, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Family lore has it that Mary Lou made the journey in the horn of an RCA Victor Victrola. Virginia played on an old-fashioned pump organ, often holding Mary Lou on her lap to keep her out of mischief. One day while her mother was pumping up the organ, little Mary Lou’s fingers beat hers to the keyboard and picked out a melody. Mary Lou was three. Later on, in her lectures and demonstrations, she would point out the value of learning through observation: “I watch,” she would tell her students.

By the age of six, Mary Lou was professional enough to be known throughout Pittsburgh as “The Little Piano Girl,” and was playing parties for white-society people, such as the Olivers and the Mellons. As a youngster, she sat in with the Pittsburgh Union Musicians’ Band, and she played with Earl Hines’s musicians and McKinney’s Cotton Pickers when those bands were in town.

Early in 1924, a black vaudeville show, Buzz n’ Harris’s Hits and Bits, came to town. Its piano player went missing. In the search for a replacement, Harris was led out to East Liberty, the black suburb of Pittsburgh, where he found her playing hopscotch. She played the show that night, and traveled with the show that summer, mostly in the Midwest and South, on the. Theater Owners’ Booking Association (TOBA) circuit, which consisted of rundown vaudeville houses owned by whites but catering to blacks. The performers were black. In semi-proper circumstances, the TOBA was referred to as Tough on Black Acts. When things got down and dirty, it was called Tough on Black Asses.

The pit band was led by John Williams, who played alto and baritone sax. Mary Lou (then surnamed Burley, after a step-father) remained with Hits and Bits for a good while. She married Williams in Memphis in 1926, traveled on the B. F. Keith Circuit with Seymour and Jeanette in big-time vaudeville where the theaters were large and glamorous and the acts were white. The only other black act Mary Lou recalled on the circuit was Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. She recorded with John Williams’s Syncopators in 1926 and 1927 in Chicago She stayed behind in Memphis to continue leading the band while Williams went to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to play with Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy. After a short period, she rejoined him. Replacing a missing pianist, she recorded with the Clouds of Joy in 1929 and 1930, though she was not yet an official member of the band. She composed her first arrangements (“Messa Stomp” and “Mary’s Idea”) for these recording sessions, and was heard to full advantage as a strong two-fisted swinging stride pianist with the band. She made the first recording under her own name in 1930: “Nite Life,” a brilliant exposition of stride piano on side A and “Drag ‘Em,” a blues, on side B. Thus, from the first recording under her own name, she established the fact that she would approach music in diverse ways.

Mary Lou Williams remained with Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy from 1929 to 1942—the bulk of the swing era in jazz. Not only did she play piano, appearing on more than 180 recordings with Kirk’s orchestra, she also composed and arranged the music for many of those sides. Her compositions of the period include “Walkin’ and Swingin’,” “Froggy Bottom,” “Little Joe from Chicago,” “What’s Your Story, Morning Glory,” “Steppin’ Pretty,” and the beautiful “Big Jim Blues.” In 1937, she wrote the boogie-woogie-based “Roll ‘Em” for Benny Goodman’s big band which became something of a hit. Decca also recorded Williams separately as a pianist with rhythm accompaniment in 1936 and 1938. The title of one of them, “Swinging for Joy,” is just right.

In 1942, Mary Lou Williams left Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy and returned to Pittsburgh to stay at her sister’s house. She then formed a septet that included the trumpeter Harold Baker and a youthful Pittsburgh native, the drummer Art Blakey. By 1943, she was in New York, where she earned a following as a highly skilled solo pianist who composed for various small combinations of musicians, and occasionally for big bands. In 1944, Duke Ellington played her arrangement of Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies” in concert at Carnegie Hall. It later became known as “Trumpets No End.”

In 1944, Mary Lou Williams found a champion in Moses Asch, owner and producer of Asch Records. Between 1944 and 1947, she recorded more than fifty sides for his various labels, including Disc and Folkways. In 1944 alone, she recorded six separate times. All the arrangements were her own, as were most of the compositions. The groups included, as sidemen, Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas, Vic Dickenson, Bill Coleman, Edmond Hall, Frank Newton, and Josh White. In 1946, she recorded a translucent solo piano album, and in 1947, Folkways issued her first bop recordings with Kenny Dorham. In 1945, meanwhile, she had composed The Zodiac Suite, writing harmonically advanced music not formerly associated with jazz. She recorded the suite for Asch Records with piano, bass, and drums.

She soon scored the suite for small chamber orchestra and jazz instruments, and premiered the work at Town Hall in December 31, 1945. The following June, she scored three sections of the suite for seventy pieces and played these with the New York Pops Orchestra at Carnegie Hall.

Mary Lou Williams was one of the major stride and swing performers who successfully made the transition to bop. For Benny Goodman in 1947, she composed two bop-influenced pieces: “Lonely Moments” and “Whistle Blues.” For Dizzy Gillespie’s big band in 1949, she composed the bop fairy tale “In the Land of Oo Bla Dee.”

In 1952, she left for Europe for the first time. A nine-day engagement stretched out to two years. She played in England and at length in France, (at the Boeuf sur le Toit and a club named for her, Chez Mary Lou). She recorded for six different companies and toured the continent.

Williams’s own musical development is illustrated in a poster drawn to her specifications and ideas by the artist David Stone Martin. It is in the form of a tree and she called the work The History of Jazz. It boldly shows her deeply held conviction about the origin of the music.

Down into the earth of human experience (African-American human experience), which Williams called SUFFERING, the strong roots descend. From these roots, the tree grows,—thick and straight. Up the middle of the trunk, in ascending order, the eras in the development of jazz are named: spirituals, through ragtime to Kansas City Swing, then bop. The blues are not just another stage, or step, in the evolution of the music, but run up both sides of the tree, originating in the roots. They ascend on the right into the leafy branches, but are severely stopped on the left, where chopped-off branches are seen. On these dead sticks appear such words as “cults and black magic,” “mere exercises,” and “classical books.” On the leaves of the tree are the names of the vital musicians in whose music the blues flourish.

The importance of the blues cannot be overemphasized in Williams’s music. She would often say: “What I’m trying to do is bring back good jazz to you with the healing in it and spiritual feeling” and “The blues was really important—this is your healing and love in the music.” In her teaching and talking about jazz, she never tired of pointing toward “this feeling.” She’d say, “It’s all spiritual music and healing to the soul.” Part of this was in defiance of those who would call jazz “the devil’s music,” and part was in defiance of those who would play music filled with technique but very little feeling.

Langston Hughes called the blues “hymns” to the secular region of man’s soul. Williams went a step further, and called the blues “the spiritual feeling” in jazz. In one deft phrase, she dispensed with any false division in thinking about human life—or about black American music.

In 1962 and 1963, when Mary Lou Williams Presents Saint Martin de Porres was made, and in 1964 when it was released, Williams made an effort to explore the nature of the music she was creating by writing about it. She distributed a single mimeographed page under the title of “Jazz for the Soul” everywhere she played.

Between 1971 and 1978, Williams recorded eight complete albums, including Zoning, another masterpiece for Mary Records (reissued as Smithsonian Folkways 40811), and contributed to three others. In 1977 and 1978, she appeared at Carnegie Hall, first in duets with the avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor, and second with the swing-era musician Benny Goodman, again giving some idea of her scope and versatility. Both concerts were recorded.

In the fall of that year, Williams entered the final period of her life and career, when she accepted the position of artist-in residence at Duke University, in Durham, North Carolina. It was a deeply fulfilling period for her. She loved the students, and they loved her. She received the Trinity Award, given directly by the vote of the students. Williams battled bladder cancer for the last two years of her life. She never complained, and continued her intense schedule through the fall of 1980. In the final three months of her life, she was bedridden, but continued to compose. Her last work remains incomplete—a composition of 55 winds, piano trio and chamber orchestra called The History of Jazz, a history she largely lived and helped create.

Mary Lou Williams died on May 28, 1981, in Durham. At her funeral, in New York, at the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola (where she had been baptized), the musical world gathered. Dizzy Gillespie played, and Benny Goodman and Andy Kirk attended. Excerpts from Mary Lou’s Mass were sung. Her body was taken to Pittsburgh, where another mass was celebrated, with family and friends attending, in the Jesuit church of Saint Peter and Paul. She is buried in Calvary Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

-Father Peter F. O’Brien, S.J.