Our Native Daughters

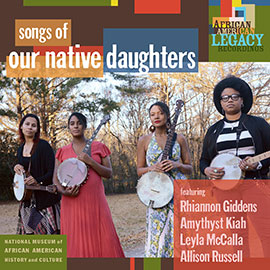

Our Native Daughters is comprised of banjo players and collaborators Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, and Allison Russell, who together use their music to highlight the experiences of black women in America. Giddens first conceived of the idea for Songs of Our Native Daughters while reading historical accounts of slavery in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. The idea was further encouraged by her observations of a more contemporary slave narrative, specifically a rape scene in the 2016 film Birth of a Nation. Following the encounter between an enslaved woman and a plantation owner’s friend, the camera shows, not the woman’s reaction, but rather the face of the “wronged” husband, who is motivated by the rape of his wife to join a slave rebellion. “As I sat in the little theater in New York City, I found myself furious,” Gidden’s explains in the album’s liner notes, “Furious at this moment in a long history of moments of the pain and suffering of black women being used to justify a man’s actions; at her own emotion and reaction being literally written out of the frame.”

Giddens is a Grammy-nominated solo artist as well as the co-founder of the Grammy Award-winning string band Carolina Chocolate Drops, and is additionally a recipient of The 2017 Macarthur Genius Award and the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Bluegrass and Banjo. For this project, Giddens brought together three other predominant black female roots artists. “Gathering a group of fellow black female artists who had and have a lot to say, made it both highly collaborative and deeply personal to me,” she explains. “It felt like there were things we had been waiting to say our whole lives in our art; and to be able to say them in the presence of our sisters-in-song was sweet, indeed. I see this album as a part of a larger movement to reclaim the black female history of this country.”

The album’s opening track showcases acclaimed blues singer Amythyst Kiah’s powerful vocals and delta sensibilities. Kiah’s musical voice came to fruition through the study of old-time music at East Tennessee State University, and she gained the attention of Giddens while performing at The Cambridge Folk Festival in the UK.

The song “Black Myself” was inspired by the lyrics of Sid Hemphill, an acclaimed Mississippi musician and the son of a slave. Kiah interprets his verse (“I don’t like no red-black woman/Black myself, black myself) as a sentiment linked to the history of intra-racial discrimination, or “the idea that being a lighter shade of black is more desirable because it means that you look closer to being white.” Kiah brings the sentiment of black pride into the contemporary American landscape, singing “I’m surrounded by many loving arms/Cause I’m black myself/I’ll stand my ground and smile in your face/Cause I’m black myself.” Backing vocals from Giddens, Russell and McCalla lift Kiah’s already soaring voice to new heights, making the song feel like an anthem for a new era.

In addition to historical documents, the four musicians draw on their own familial history with slavery, stories that were passed down from generation to generation. The insightful songwriting and heart-wrenching singing of Allison Russell is featured on “Quasheba, Quasheba”. Russell, who was a founding member of Canadian roots band Po’ Girl, and in the past five years has garnered attention as half of rock and roll duo Birds of Chicago, wrote “Quasheba” about her paternal ancestor who was sold into slavery off of the coast of Ghana. The song recounts Quasheba’s harrowing experience, “Raped and beaten/Every baby taken/Starved and sold and sold again/But ain’t you a woman/Of love deservin’ /Ain’t it somethin’ you survived.”

In her lyrics, Russell gains strength from the knowledge of her ancestors’ experience. “As we got deeper into the project, into the source material, slave narratives, and minstrel history, I kept feeling the parallels to my own life and experience,” she says. “I survived 10 years of sexual, physical, psychological abuse and dehumanizing treatment as a child at the hands of my white American adopted father. I came close to suicide, but something kept me here. A whisper of hope. A hidden light. I felt the presence of my grandmothers, great-grandmothers, and back—and I began to understand that the other side of the coin to the horror, inhumanity, abuse, pain, and fear of slavery is resilience, endurance, survival, hope, and strength.”

On the hopeful “I Knew I Could Fly,” co-written by Leyla McCalla and Allison Russell, McCalla muses about the way racism and sexism has shaped the lives of black women in America. Leyla McCalla is a multi-instrumentalist and singer of Haitian descent who grew up in New York, who toured with the Carolina Chocolate Drops for several years before launching her solo career with an album of Langston Hughes poems set to music. Her third album, 'The Capitalist Blues,' is out January 25 on PIAS.

“I Knew I Could Fly” was inspired by both the story and the guitar sound of Piedmont blues guitarist Etta Baker, a now renowned musician who didn’t release any music until she was in her 60s. “Etta didn’t became involved in the music industry earlier in her life because her husband didn’t want her to, and that fact continues to confound me. I simply can’t imagine living in that type of reality,” says McCalla.

Heartbreaking, groundbreaking, simultaneously gutting and hopeful, Songs of Our Native Daughters gives a much-needed perspective on the dark American institution of slavery. In bringing to light the specific experience of black women through the beautiful music and writing of contemporary black female musicians, collectively Our Native Daughters, the album finds new touchstones in the story of American racism. The emotion called up by Giddens, Kiah, McCalla, and Russell, in both their vulnerability and resilience, is nothing short of humbling. Songs of Our Native Daughters is a gift to the hearts and ears of Americans for years to come.