Talking Feet

The tourists and adventure-seekers who first arrived in the hills of southern Appalachia in the late nineteenth century clearly thought they were dreaming. In breathless accounts, they described the edenic land they had discovered, one that seemed to exist in a different century from their homes in the industrialized North. Instead of cities choked by smog and factory horns, there were wide open hills, populated by a peculiar, antiquated people. They farmed the land and spoke in near-Elizabethan tones. They entertained themselves at night with fiddles and banjos. Even their dancing was wild, unhinged: country frolics by the light of the moon.

Watch a full length stream of Mike Seeger's Talking Feet documentary from 1987.

These heavily romanticized reports laid the groundwork for a perception of Appalachia that the region has never truly escaped. Outsiders continue to view the mountains and their inhabitants as simple, even backwards. This attitude has colored everything from the area’s music to its politics. But as Phil Jamison notes in his book Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics, it was the locals’ dancing that truly “epitomized the ‘otherness’ of this…‘strange land’” to those early visitors. And to this day, there may be no single piece of Appalachian culture that remains more deeply misunderstood than its folk dances. Stereotypes linger despite—or perhaps because of—the public’s supposed familiarity with the tradition; I have seen “Appalachian-style” square dances as far away as Vancouver, BC. Yet these group dances, exhilarating as they may be, represent only a portion of a dizzyingly large tradition. Indeed, most Appalachian folk dances are solo dances. And for the last three hundred years, if not longer, the southern hills have been home to more styles than can easily be counted.

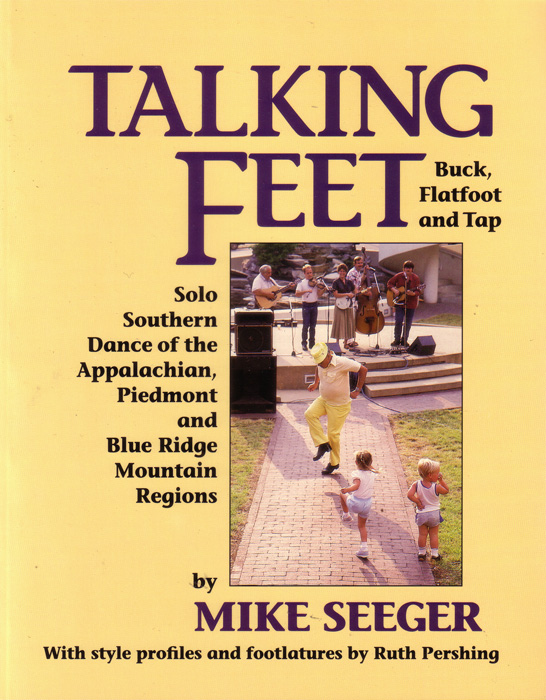

Cover of the Talking Feet DVD.

This was the misconception that the folklorist Mike Seeger set out to rectify with his excellent, woefully underseen documentary Talking Feet. The film, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, was the first serious attempt to survey and visually document the many different styles of Appalachian solo dancing. Amazingly, it remains the only one to date. While the film suffers from low production values and technology that was practically obsolete at the time of filming, it is still an essential work, propelled as much by the vibrancy of its dancers as Seeger’s rigorous and respectful approach behind the camera. It is the definitive primer on a uniquely American tradition.

Southern solo dancing was born of a combination of European, African, and Native American folk dances. The closest modern comparison, however, may be tap dancing. Generally speaking, a dancer holds her arms and torso still, while her feet flick, tap, and scrape in rapid patterns across the floor. Throughout Talking Feet, though, dancers emphasize that there are no “wrong” ways of dancing, no standardized rules or steps to follow. What a dance looks like depends largely on the dancer. Some employ their whole bodies in explosive imitations of eagles or bears; others keep so still it could be easy to miss that their feet are moving. Some lift their feet no more than six inches off the floor. The routines are often improvised, with dozens of memorized steps strung together into propulsive, highly complex rhythms. Ruth Pershing, a dancer and Seeger’s assistant on Talking Feet, told me stories of kneeling with her face to the floor while subjects danced, trying to puzzle out their steps.

-

Photograph of dancer Burton Edwards, as featured in Mike Seeger’s Talking Feet.Photo by Mike Seeger.

Photograph of dancer Burton Edwards, as featured in Mike Seeger’s Talking Feet.

These different interpretations have evolved into entirely singular forms of dancing. There are buck dances and animal dances. Hoedowns. Flatfooting and clogging. Yet labels, in their own way, are deceptive. The dance scholar Susan Eike Spalding has observed that what might be called “flatfooting” in one part of the South may be called “clogging” in another, and simply “dancing” elsewhere. Meanwhile, two dancers with wildly disparate styles might both consider themselves flatfooters. Academics have tied themselves in knots trying to establish a consistent terminology. Many, citing the dancing’s distinct percussive nature, have resorted to phrases like “rhythm-making with the feet.”

This daunting diversity helps explain why no one had attempted to document the tradition by the time Mike Seeger turned his attention to it in 1984. Seeger was no stranger to ambitious projects, and had long established himself as one of the foremost collectors of the 20th century. His recordings of Dock Boggs and Elizabeth Cotten secured the legacy of some of America’s most important folk musicians, and directly informed the music of the New Lost City Ramblers, of whom Seeger was a founding member. Still, even he was unprepared for the magnitude of this new project. “I was way over my head in this,” he would admit years later.

Cover of Mike Seeger’s book, Talking Feet.

There was a second reason that nobody had attempted the task, one that Seeger himself had no experience with: the difficulties of using a camera crew. The folk revival exploded in part because music was easily portable; the style of someone like Lead Belly could be captured (and imitated) through audio alone. Not so with dancing. Toting several hundred pounds of recording equipment into the rural South was difficult enough. The video technology necessary to document dancing was even more cumbersome, not to mention expensive, and plagued Talking Feet through its production. It required additional conditions that were not easy to attain in rural areas, like good lighting and space to film. Splicing the audio and visual together, too, took levels of precision that would have driven the most patient editor insane. Talking Feet, an 85 minute film, required 300 hours of editing over three years.

Meanwhile, a paradox had emerged. By the time video technology evolved to a manageable size, the tools that allowed for the documentation of folk traditions had become the very reason for their decline. Families were watching TV in the evenings instead of playing music or dancing. For the first time in history, older generations were dying without passing their culture on to the next. For Seeger and Ruth Pershing, who accompanied him on the various scouting and filming trips, this was evident almost immediately. Many of the dancers whom Seeger had met over the years had died, or grown too old to dance. Many had “gotten religion” and now refused to dance on moral grounds. Others simply couldn’t be found. One man had a bounty on his head. Another had run off with his mistress, only to leave her and run off with another woman entirely.

-

Ruth Pershing developed footlature—a dance equivalent to music tablature—for some of the dances that are featured in Talking Feet.

Ruth Pershing developed footlature—a dance equivalent to music tablature—for some of the dances that are featured in Talking Feet.

The pressure mounted. These were the days before cell phones and Google Maps, and the trips sent Seeger and Pershing scrambling across the mountains, town to town, pay phone to pay phone, road atlases spread crazily across the dashboard. “It was maps, maps, maps,” Pershing remembered. Rural towns of 500 people, remote farms at the ends of rutted-out driveways. Film shoots had to be improvised in convenience stores and schoolhouses, the desks shoved hastily aside. “There were disappointments,” Pershing said. Dancers who only knew a handful of steps, dancers who were clearly “a shadow of what they’d once been,” dancers who froze up in the harsh lights and expectant gaze of the camera. “We saw this as a first step,” she told me. “We both thought there was much more depth to be found, people dancing a greater variety of steps.”

And yet for all the disappointments, Seeger and Pershing were ultimately able to document a remarkable collection of dancers, men and women whose talent is evident to the most naive of viewers. Their performances are almost hypnotic: the driving rhythms, the casual intricacy of their steps, the odd juxtaposition between the energy of their feet and their soldier-still bodies. Again, one need not be a dancer to recognize the incredible diversity on display. There’s Algia Mae Hinton, who steps in a sly, teasing pattern around the room while playing a guitar behind her head. John Dee Holeman, whose “steam train” dance (his feet shuffling and scraping and stomping in a circle on the floor, faster and faster) does sound an awful lot like a train pulling out of the station. D. Ray White, whose entire family—including the four-year-old—joins in a rapid-fire group dance on the trailer of their porch. Many of the dancers are black, a not insignificant detail in a culture where the contributions of black musicians are too often glossed over.

Seeger, too, allows the dancers and their performances to speak for themselves, rather than smothering them with tedious voiceover or attempting to spice up the dancing with close-ups and quick cutaways. Pershing explained that such editorial manipulation was “disrespectful of the tradition. It wasn’t about the art of what they were doing. It was to try to make it seem like these people were wild.” Seeger insisted instead on long takes and full-body shots. It was an unconventional decision that didn’t make the filming process any easier—full-body shots required some 25 feet between the camera and the dancer, no easy feat when you’re filming in a small town convenience store. But it created a fluidity to the film, an intimacy that invites the viewer to enter the frame, lose themselves in the dancing.

Talking Feet never received the wide distribution that Seeger hoped it would, and the film has been relegated to something of a footnote. Yet, by gracefully revealing the complexities of a long-overlooked tradition, and successfully giving voice to its dancers, Talking Feet is one of the great accomplishments of Mike Seeger’s career. It is a benchmark of folklore that deserves to be seen and studied more widely, and the truth it suggests celebrated: that these are not the wild frolics of an uncivilized people. On the contrary, it is art of the highest order.

Will Preston is a writer, journalist, and critic. His prose has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in publications across North America, including Maisonneuve, The Masters Review, and PRISM International. He is working on a book about Mike Seeger and old-time music.