-

UNESCO Collection Week 31: Exploring Regional Identity - The Music of the Kurds and West Futuna

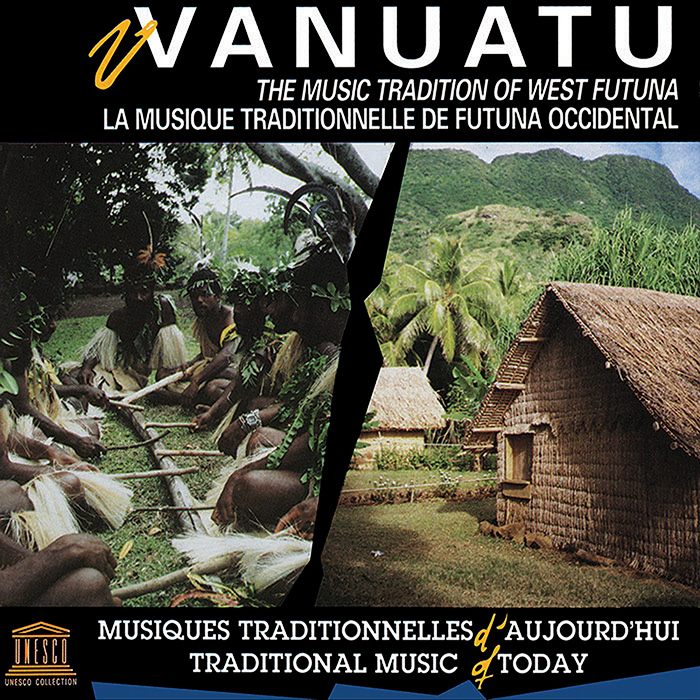

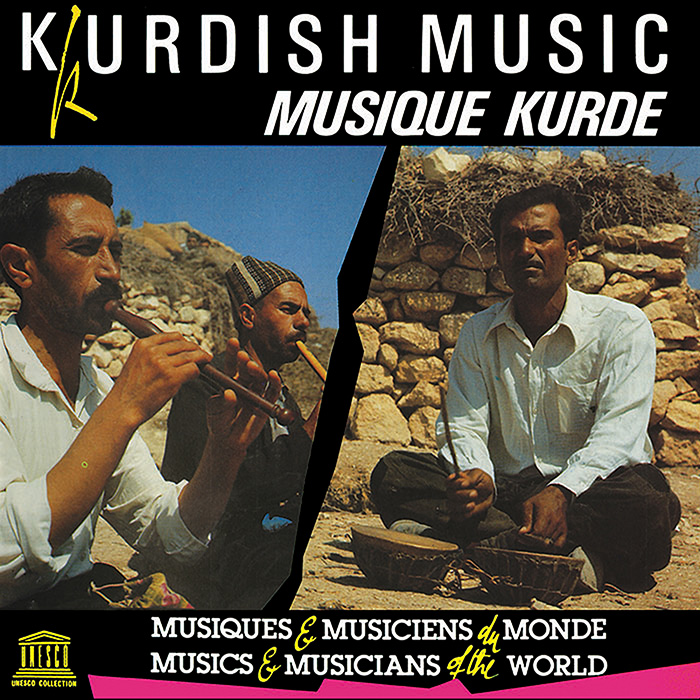

This week’s UNESCO releases, Kurdish Music and Vanuatu: The Music Tradition of West Futuna, give interesting insight into regional identities and their development over time.

GUEST BLOG

By Grego Applegate Edwards

Kurdish Music and Vanuatu: The Music Tradition of West Futuna represent important examples of how regional identities can develop over long periods of time. While these identities remain distinct, they have definite affinities to their neighboring musical cultures. In the case of the Kurds, the classical music of Iran stands out. In West Futuna, the country’s relationship to Melanesian and Polynesian musico-cultural complexes helps situate their position on the musical map. The culture of neither group has unfolded in total isolation, something we find true of any regional-cultural complex across the globe today. The more we learn, the more we discover interpenetration and cultural diffusion across borders during the long history of our planet.

Oceania's island culture experienced more intensified cultural exchanges between different groups, while the Kurds remained relatively isolated in the mountainous climes of Turkey, Armenia, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. However, their geographic location allowed the Kurds to have influences over longer periods of time, perhaps more so than the island nations. We know there are elements in the musical culture of both regions that are very old and relatively new. The search for the ultimate "Ur" music (the pristine style) has fascinated many for centuries, but in the end we cannot reconstruct such music with accuracy.

The West Futuna island peoples are said to have migrated from Polynesia to their current locale in Melanesia generations ago. As a result, the song and dance forms found on Vanuatu: The Music Tradition of West Futuna echo those of that region combined with the more recent adoption of Melanesian aspects.The use of guitar and ukulele is characteristic in the string band songs that start off the album, recorded in the 1990s. Atypical of regional string bands, however, is the presence of two percussion instruments, the bottle piano—a set of glass bottles tuned by filling with varying amounts of water—and a bamboo tube set of varying lengths; both instruments produce distinctive, pitched rhythmic patterns when struck. This addition gives the string band an almost gamelan sound or, alternatively, the equivalent of the syncopated oil-drum ensembles in the Caribbean. The songs celebrate kava drinking, love of homeland, AIDS and malaria health awareness, and other topics. They are the popular music of the day, but of course maintain a distinctive acoustic style that has regional folk roots. The characteristic island harmonies of the singers add to the appeal of these songs.

The church songs featured on the album are typical of the adapted choral style that came about as missionaries brought the traditional harmonized hymns to the various islands. These hymns then were subject to local modifications that set them apart and gave them great appeal and local singularity.

The dance songs were once forbidden by the missionaries, but somehow survived underground; they have formed an important part of the cultural heritage since independence in 1980. Some have definite resonance with rural and/or historical Polynesian traditions. However, a few others sound almost like stylized vocals imitating bugle calls.

The group of four memorial songs round off the recording with more chant-like monophony, again recalling what must have been earlier musical forms.

West Futuna gets a comprehensive overview here with some beautiful folk-art music that points both to a rich past and, one believes, an even richer future. In my opinion, it is an important addition to the body of recordings from Oceania and a pleasure to hear and enjoy.

Kurdish Music is a well-paced album of excellent performances recorded in the 1970s. As West Futuna’s music reflected Polynesian and Melanesian traditions adapted uniquely to that island people’s own sensibilities, so also the Kurds have taken Persian/Iranian forms and made something of their own. This of course presupposes that music can change and evolve as language does, with the prototypical Indo-European language giving rise to families of languages, and musical prototypes doing the same.The album opens with a long improvisation based on “Naghma Jabali Wa Binafshe,” a love story and melodic form which can be performed with sung text or, as here, without. The Kurdish five-note mode is at the forefront in most all music from the region, here included. Two tanboura lutes alternate in intricate and involved improvisations, one larger, called the meydan saz, and the other a smaller, higher pitched instrument of the tanboura family. The concluding section is a moving, rhythmically lively strummed duet that is the expected finale.

Next is the droning intricacy of two double-reed instruments know as zorna, with the double-headed tabl drum providing straightforward rhythmic accompaniment.

A lively number follows for two pik flutes, paired tumbalak drums and a pair of copper zil cymbals. This is typical music for Kurdish wedding celebrations and has a correspondingly joyous feel.

Next is a full-fledged bardic song sung and played by the lead musician on the tanboura to the accompaniment of a drone on the meyden saz. According to the liner notes, this is in a song style typical of Iraqi-based Kurds. The singing has great artistic appeal and reminds us that Kurdish musicians in the local tradition are thought of primarily as "storytellers," somewhat like the itinerate troubadours of medieval Europe. As such this encapsulates the center of Kurd musical tradition.

The final number is for tanboura solo, bringing us full circle.

Grego Applegate Edwards is a musician/composer and music writer of long standing. He studied ethnomusicology as an undergraduate and graduate student and continues to learn by listening and studying examples of our world heritage every day. He writes three columns on music every weekday. The principal blog address for these is www.gapplegatemusicreview.blogspot.com He can be reached at Google+.

UNESCO Collection Week 31: Exploring Regional Identity - The Music of the Kurds and West Futuna | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings