-

UNESCO Collection Week 32: Deep Chant Among the Ruins

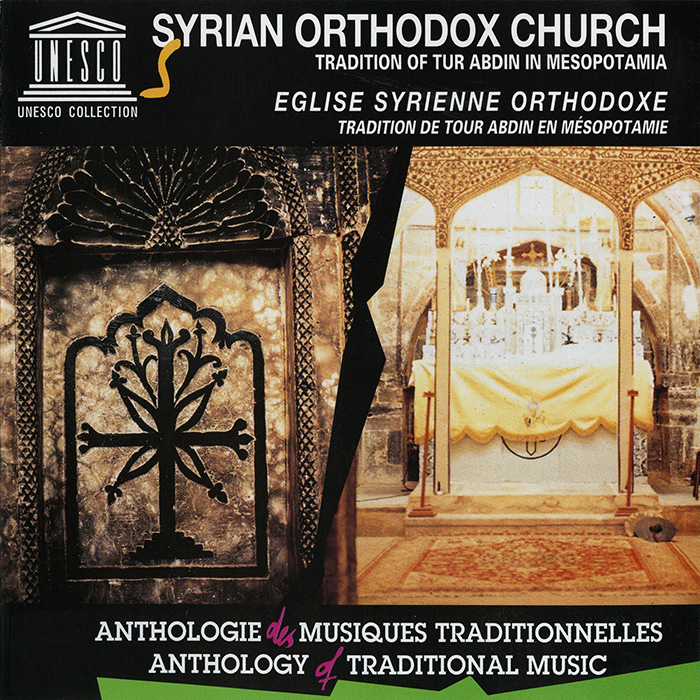

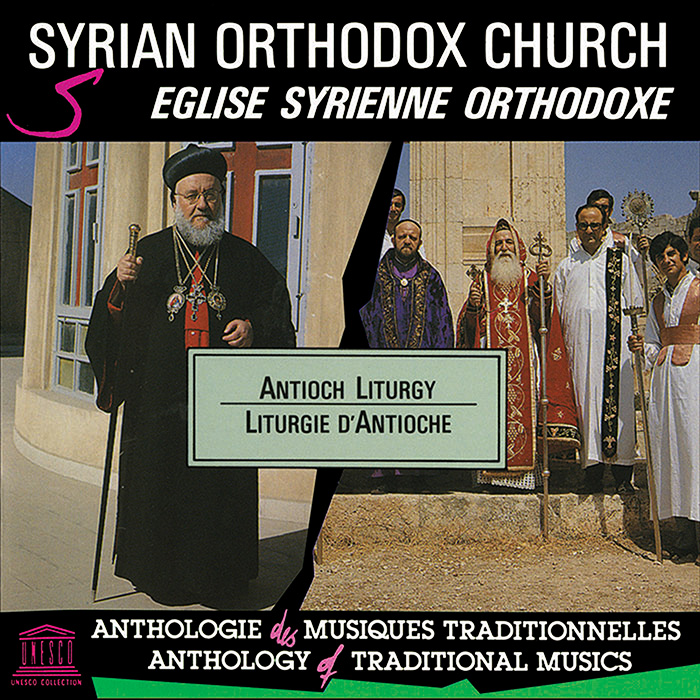

Week 32 of the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music features recordings from the Syrian Orthodox Church, Syrian Orthodox Church: Tradition of Tur Abdin in Mesopotamia (1973) and Syrian Orthodox Church: Antioch Liturgy (1983). The Syrian Orthodox Church traces its origins back to the earliest days of Christianity. According to the New Testament, Antioch is where Christ’s followers were first referred to as Christians (Acts 11:26). Those faithful to this denomination have endured much persecution, resulting in widespread immigration. In addition to the Middle East, members of the Syrian Orthodox Church can be found today in the Americas, Europe, and Australia.

GUEST BLOG

by David Roche

In the key Syriac Orthodox liturgial text Beth Gazo D-ne’motho (“The Treasury of Chants”), patron saint and poet Ephrem the Syrian (306—373 CE) encoded the message that redemption is the ultimate reward for the faithful on the everlasting early battleground of good and evil. His texts contain a universaility and timelessness as spiritually vital today as it was 1,800 years ago. Similarly, the UNESCO albums released this week, Syrian Orthodox Church: Tradition of Tur Abdin in Mesopotamia (1973) and Syrian Orthodox Church: Antioch Liturgy (1983), serve as contemporary documentation of the endangered traditional liturgical sounds rising from the din of war-torn Syria.

Outside the combat zone, we are confronted with daily headlines (“Syrian forces hit rebel positions on the coast,” “Syrian nuns kidnapped,” etc.) that reinforce the news of an unabated, horrific situation in Syria, with conservative estimates of 150,000 or more dead in the past three years of civil unrest.1 It is important to consider the long history of conflict in the region when reviewing these albums, which feature a cappella chant soundtracks. These chants become temporarily lodged in the listener’s consciousness. The unheard sounds of an imagined accompaniment—mortar shelling, exploding body armor, keening razor wire, strafing warplanes, and truck-mounted machine guns blasting the ancient walls of Saadullah al-Jabri Square in Aleppo—cast an unvoiced rumble.

First recorded in eastern Turkey (Mesopotamia/Assyria) and Aleppo, Syria, these sonic documents may have come to represent recordings of the last of a tradition handed down from one congregation to the next, hymn by sacred hymn, surviving among the ruins of the war zone. Only time will tell, for this is a sacred tradition that has managed to survive devastating ethnic and sectarian battles since the earliest centuries of the Christian era.

The Eastern and Western rites of the Syriac Orthodox Church represented on these recordings encompass a sonic diptych (two images on flat plates connected by a hinge), revealing some key elements of ancient Syriac poetics and ecclesiastical ritual that have existed since fifth century CE during the Patriarchate of Antiochia.

The Beth Gazo book of hymns remains the canonic text, divided into eight parts according to the traditional eight modes (oktoechos) of Syriac chant, of which four remain extant in performance.2 A Syriac Orthodox deacon can theoretically still recite an authentic text written by St. Ephrem in the fourth century, recognize its hymn setting (qolo), and chant it with the orally transmitted melody—a feat of liturgical musicianship that is remarkable in its longevity and reminiscent of the precious survival of Vedic and Buddhist chant traditions with even older lineages.The melodies and their variants (shuhlophe) have antecedents in the traditional Greek modes: Dorian, Phyrigian, Aeolian, Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian. The assignment of a specific mode to the entire day’s offices is rotated according to a formula that emphasizes a numerological shifting of the tone row from one day to the next. That is, if Sunday’s melody is sung in the first mode, then Monday’s is sung in the fourth mode, and so on through the eight modes. The result is a circle of numeric, if not sonic, fourths, with exceptions for feasts and High Holy Days, which have a specific mode assigned. In this manner, all the modes become linked through chant geometrics in song lines, establishing a symmetrical pattern of mystic logic. In addition, the texts themselves are constructed according to Syriac poetics that feature acrostic patterning, a technique requiring precise control.

Documentation of the tradition of Tur Abdin, recorded by the late Palestinian ethnomusicologist and composer Habib Hassan Touma (1934—1998), maintains a feeling of in situ ambiance with its lengthier tracks, including the 45-minute mass in the first mode (qadmoyo) on track one. Featuring the choir and monks of the Deyrulzafaran Monastery and priests from the city of Mardin and Diyarbaker, Turkey, the mass is chanted monophonically and syllabically in emphasis of the text. With the occasional lone sound of the swinging censer (container for burning incense during religious ceremonies), the contrast of the soprano and baritone voices, as well as non-melismatic recitations and alternations of solo and chorus performance, provide a moving aural experience.

Track 2, “B’utho,” in the eighth mode (thminoyo), performed by priests of three lineages and recorded at St. Barsum in Midyat, Turkey, opens with an almost Islamic “call-to-prayer” soloist. This is followed by dynamic baritone choral intoning, the most dynamic chanting on the entire recording. The melodic contour and tone row suggest the Phyrigian mode and the more melismatic singing style reinforces those influences, characteristic of the Eastern rite.

Syrian Orthodox Church: Antioch Liturgy provides a link to all the branches of Eastern Christianity from Turkey, Syria, and Iraq to the flourishing community in Kerala, India, and to other Syriac Orthodox congregations in the world diaspora. This is the tradition that represents the oldest surviving liturgy in Christianity, situated in a region where a village like Ma’loula still exists and Aramaic, spoken by Jesus Christ, can still be heard. While the Eastern tradition is best known for melismatic and improvised chanting that ranges over an octave, the more conservative Western tradition is characterized by metrically-paced, syllabic singing, which emphasizes the sacred text.The second track, “Qolo” (“At the Outer Door”), a hymn for mixed male and female a cappella choir of the Church of St. Ephrem in Aleppo, serves as an ideal example of Western rite performance practice. Call-and-response between a soloist and the chorus, inflected melismatic glides within a tetrachord, a modulation to an upper tetrachord, and strophic construction all characterize the tradition and are beautifully recorded here. Other tracks feature moving solo chanting that reverberates within domed sanctuaries, a traditional choir of deaconesses of the Church of the Virgin, and a movingly rendered communion chant (track 6) featuring a fluid choral chromaticism that builds to a swirling and soaring pinnacle of acoustical majesty.

AudioThe ringing of higher female soprano voices, in a chant tradition that is anchored in text by male baritone voices holding down the bottom end, opens up a spaciousness that is not often heard in most other liturgical chant forms (which tend to be exclusively male). St. Ephrem, it is said, instituted the deaconess choir in the fourth century CE, a remarkably humane institutional model for its time. While some Tibetan Buddhist or Bon chanting by males also opens up a spacious and audible overtone range, the higher harmonics of the female voices of Syriac Orthodox chant are powered and energized by the strike tones of the choral intoning.

For the aficionado of chant traditions, these UNESCO recordings are essential. More current recordings by the Edessian Preservation Initiative based at St. George’s Syriac Orthodox Church in Aleppo, supported by Smithsonian Folkways, for example, are also noteworthy and to be commended.3 However, current ethnomusicological efforts have been thwarted. Two “men of peace”—the Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Boulos Yazigi and Syriac Orthodox Metropolitan Youhanna Ibrahim, both of Aleppo—were abducted in April 2013, and the city’s Christian neighborhood has been thoroughly shelled.

Contrasting the sounds of war in the present with the resonating and atmospheric melismatic intonings of the Orthodox deacons and mixed choirs heard on these recordings can create a peculiar sensation of floating in an impossibly endless liminal embrace, between extreme, if not disparate, worlds. It is the endless story of war and peace. In the prophetic words of St. Ephrem:4

If what makes you wander is the voice of Moses,

The voice of the Lord will gather you.

But if the two voices trouble you,

Nature, with which they are bound together, will testify…Dr. David Roche writes on Asian and Native American ritual and performing arts. He is the former executive director of Old Town School of Folk Music, Chicago, and artistic director for World Arts West, San Francisco.

Disclaimer: The views expressed by guest writers in Smithsonian Folkways News & Notes are those of each individual contributor and do not necessarily reflect the views of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, the Smithsonian Institution, its staff or affiliates.

1United Nations says at least 150,00 in July 2013; they stopped keeping track of death toll in January 2014.

2 Syriac Orthodox Resources, http://sor.cua.edu/bethgazo/

3 For more information, see: www.washingtoncitypaper.com/blogs/artsdesk/visual-arts/2014/05/29/punk-drummer-with-a-camera-jason-hamacher-is-now-a-syrian-art-preservationist/

4 Excerpted from “Praise to the Omniscient,” with translation by Kathleen E. McVey.

UNESCO Collection Week 32: Deep Chant Among the Ruins | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings