-

UNESCO Collection Week 50: Recording the Music of the Central African Republic

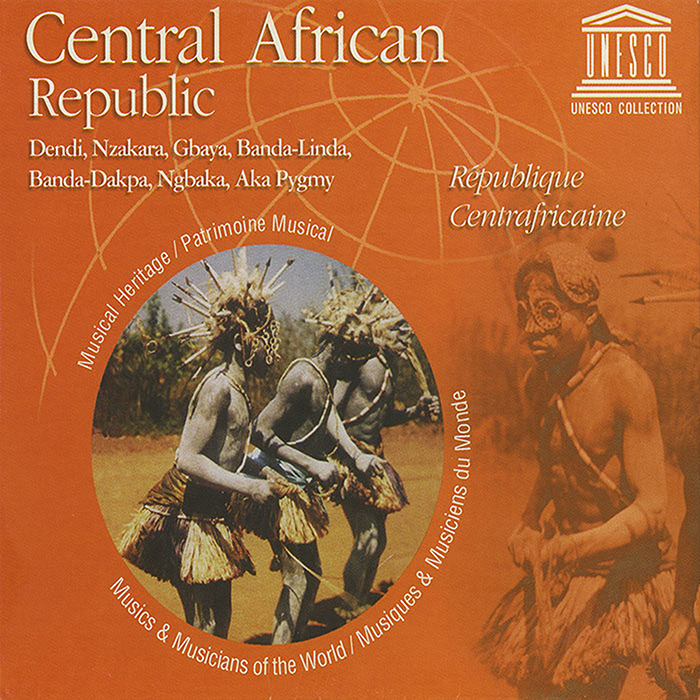

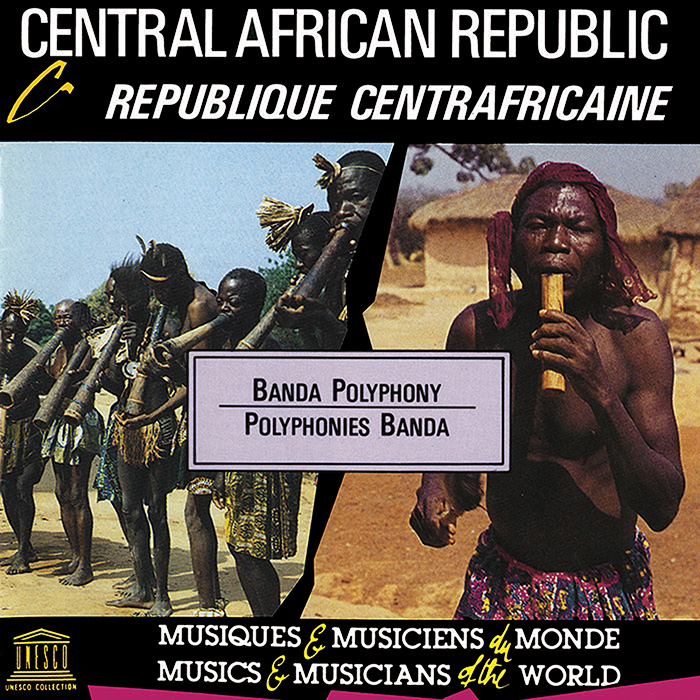

In 1963, Simha Arom traveled to the Central African Republic, not knowing his project would ultimately lead to the most substantial and expansive collection of the country’s vast range of traditional music. Rob Sevier interviewed Arom about his experiences recording this week’s UNESCO releases: Banda Polyphony and Central African Republic.

GUEST BLOG

by Rob Sevier

Simha Arom arrived in the Central African Republic with a fairly specific set of instructions from Israel’s department of International Cooperation, part of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs: assemble and educate a national brass band in the capital city of Bangui. There’s no doubt that Arom was eminently qualified, as first horn in the Israel Broadcasting Authority Symphony Orchestra. However, his project would have indoctrinated a small number of Central Africans in Western musical modes and proficiency in staid marches, with finite and likely uninspiring long-term results. It was only through a happenstance of his disembarkation date that his course was permanently diverted. Arom arrived in Bangui on November 30, 1963, one day before the nation’s Independence Day.“It was a very important date for my future,” Arom notes. He was 33 at the time. The office of President David Dacko had organized an expansive celebration which comprised the transport of a hundred musicians from the bush into the city center to perform their respective tribal repertoire. Among them was a horn orchestra of the Banda Linda tribe and an Aka Pygmy group. Their music, in particular, moved Arom profoundly.

Arom quickly discovered that there were already two brass bands in Bangui. Neither was very impressive, but attempting to add a third to the marching band landscape seemed superfluous. Without a task at hand, he set up a meeting with the president and conveyed to him the mutual benefit in having Arom document the abundance of regional varieties of music. Dacko offered a government-owned car and wrote a letter to national radio of the Central African Republic, instructing them to supply Arom with a recorder. With a mono Nagra in hand, he taught himself recording techniques. “In Bangui I made recordings to test myself and my sound recorder.” Soon he was heading into the bush, either alone or with collaborators who would help with translations or transcribing song titles.“I am a total autodidact in ethnomusicology,” Arom says. Despite a lack of training and knowledge of what commercially available recordings existed at the start of his work, he had a completely natural inclination for this discipline. “Recording is like making photographs; you can make good photographs and bad photographs on the same subject. You have to find a way to make a balance so you can hear details.”

Arom spent the next years of his life in the Central African Republic, recording as much and as often as possible. “I only went to small tribal villages. Sometimes they thought I’m a crazy man. Who comes to record music in a village?” He was fortunate to be able to capture music that would soon become very difficult to document at all.

AudioA hallmark of Arom’s work as a recordist is his engagement with the action. “The secret is that I’m not in a stable position. I move. I never use a microphone stand.” The recordings contained on Banda Polyphony, originally issued in the Netherlands by Philips as part of their UNESCO Musical Sources series, are immediately notable for their intimacy. This recording was made between 1972 and 1974, after Arom traded his mono Nagra for a stereo model. The sound is multidimensional by comparison. “Ndraje balendo (initiation song)” pummels the listener with sounds, seemingly from all sides. There is no academic distance here. One gets the sense that the recordist has a wide-eyed excitement for the experience and wants to get deeper and deeper inside, perhaps like a fan at an arena concert, pushing to the front of the stage.

The Banda cultural group, and subgroups such as the Linda and the Dakpa (the focus of the album Banda Polyphony), had a particularly complex musical tradition. “The ensembles consist of anywhere from ten to eighteen instruments,” Arom writes in the annotations to this recording. What’s heard are not always the individual instruments, but the polyphonic interweaving of the sounds they produce. This recording is a fine example of the hocket-like methods of Banda musicians, which Arom defines as “the interweaving of several rhythmic figures located on different pitch levels in a specific scalar system” in a paper from 2010.

Audio“Song for ‘Thinking’,” which was recorded in 1964 or 1965 and was first presented on the Central African Republic LP issued by Bärenreiter-Music aphon, is another standout example of what makes Simha Arom’s recordings so memorable to the ethnomusicologist and casual listener alike. Arom here is still using his mono Nagra. The title, “Song for ‘Thinking,’” refers to a whole category of songs performed by the Gbaya tribal group with two male vocalists accompanied by a sanza. The sanza is a rhythmic instrument similar to an mbira, and the Gbaya style uses what Arom identified later as the property of “rhythmic oddity,” ostensibly asymmetric rhythms that in fact conceal elegant mathematical properties. Arom observes of these songs for “thinking” in his annotations: “[They are] is sung for the performer’s own pleasure rather than for any listener’s.”

Arom remained in the Central African Republic for four years during this initial visit, leaving two years after the president, Dacko, who had become his patron, was deposed on New Year's night in 1966. Before Arom left the country, he had formed the nation’s first museum, the Musée Boganda, and been its first director. He also supplied copies of his recordings to the national radio, which then broadcast music that the nation had never heard before from peoples previously unrecorded - or only poorly recorded and sometimes incorrectly identified.

Arom arrived in the Central African Republic with no recording experience whatsoever and, having created the most thorough archives of music from the Central African Republic that exists, unsurpassed to this day. Arom was drawn to music that was so intricate that there was nothing comparable in Western music at the time. For a discussion of how Arom’s recordings influenced a generation of composers and music theorists, see Fred Gales’ enjoyable and insightful blog entry from Week 40: Music of the Aka & Baka Pygmies.

Special thanks to Fernando Nathalie, Michelle Kisliuk, and Simha Arom, for his illuminating interview.

Rob Sevier is a co-founder of The Numero Group (www.numerogroup.com), a record label that specializes in discovering the most obscured archival recordings. He has produced projects for numerous other labels, including Drag City, Locust Music, and Now Again, and written for publications like The Wire and Sound Collector. To tie it all together he DJs nationally and internationally, touring Europe, the UK, and Canada. While doing all of the above, and largely unrelated to his other activities, he has amassed a considerable collection of ethnographic recordings on LP, CD, and cassette.

UNESCO Collection Week 50: Recording the Music of the Central African Republic | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings