-

UNESCO Collection Week 58: Lyric, Epic, and Everyday Life in Myanmar and Ethiopia

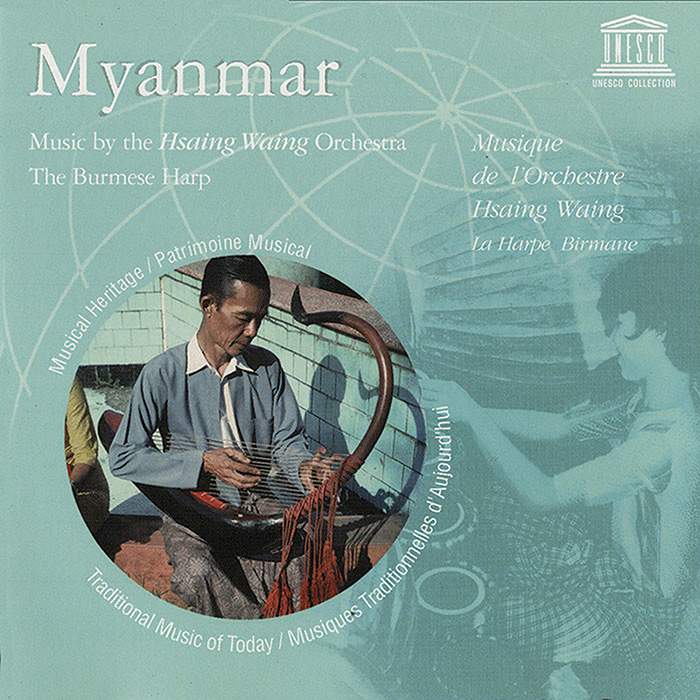

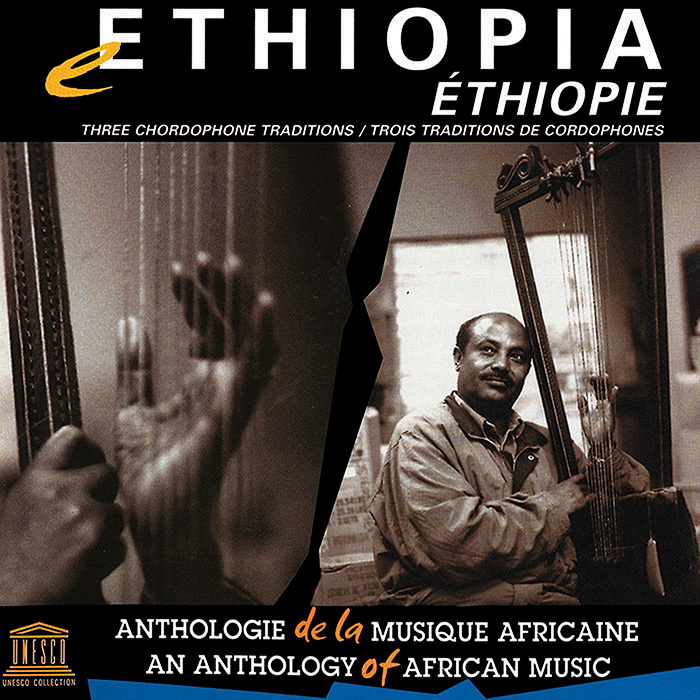

This week’s UNESCO releases are Myanmar: Music by the Hsaing Waing Orchestra; The Burmese Harp and Ethiopia: Three Chordophone Traditions. These albums offer several traditional music forms from each country. Here, we examine their differences and underlying similarities.

GUEST BLOG

by Nathan Katkin

Myanmar

Two distinct genres of music are featured on Myanmar: Music by the Hsaing Waing Orchestra; The Burmese Harp, identified by the performers as chamber and orchestral music. The former is a delicate, mannered performance for a solo harpist, sometimes accompanied by a percussionist; the latter consists of ensemble pieces for orchestras of percussion and woodwind instruments, centered on the pat waing, a set of 21 tonal drums played with the hands, which defines the melodic structure of the piece.As a Classics student, what fascinates me about these two genres is their relationship to the poetic traditions of Myanmar. Although many of the pieces in both categories are now performed without vocal accompaniment, their structure and composition originally derive from vocal performances of poems. This vast body of poetry is collected in two volumes, the Maha Gita and the Gita Wi, and knowledge of which is considered essential for musicians in the region. The poetic tradition of Myanmar contains both lyric poetry and epic sagas, transmitted to Myanmar from India through the pre-11th century migrations of the Mon and Pyu peoples. The chamber music of the solo harp grew from the vocal performance of lyric poems, while the orchestral pieces accompany dramatic, narrative dance performances of the epics. Accordingly, the chamber pieces exemplify the self-contained intricacy and beauty of the lyric, while the orchestral pieces capture the vast scope, narrative motion, and adventure of epic.

Both of these art forms flourished during the 15th century, when the Burmese monarchy had its capital at Mandalay. British colonization deprived the local kings of much of their political power, leading the monarchs to focus their energies on the cultivation of the arts, and, more specifically, on the grandeur of their own lifestyle. The musical traditions presented on this record formed amidst this period’s grandiose court rituals, and in their intricacy seem very much a product of the court, not unlike the Rococo style of 18th-century France. Like Rococo, their vitality is undiminished by their stately provenance.

This chamber harp performance by Maung That Win epitomizes both the musical complexity of the genre and the melancholy beauty of the pulé mode (as with Indian ragas, Burmese harp performers select their modal scales based on the season and time of day). With lilting rhythms and understated, repeated melodic motifs, the tune shifts and builds in intensity almost undetectably until a series of simple, elegant phrases at the conclusion ring calm and clear. The presence of the lyric poem from which this piece originates is palpable.

AudioThis orchestral piece serves as the overture to performances of the Ramayana, an epic of Indian origin which narrates the journey of Rama, an incarnation of Vishnu, to rescue his wife Sita from Ravana, a neighboring king who has abducted her. “The seven dances” cycles through an invocation of the gods, the musical themes which form the leitmotifs identified with the epic’s major characters, the entrance of the characters of themselves, and then a series of vocal chants describing and foreshadowing the characters’ sorrow. The force of the arc of the entire epic is encapsulated in the protean music of its overture. This would have been performed with dancers enacting the major roles.

Ethiopia

This album presents three different string-instrument performance traditions of Ethiopia: the bägänna (ten-string lyre), the krar (five- or six-string lyre), and the masinqo (single-string spike fiddle). Each carries different cultural associations. The bägänna, for example, is regarded as almost sacred; it is the instrument of monks, used for private meditation, and, according to legend, was played by David to cure the insomnia of King Saul in biblical times. The krar, on the other hand, is known as “the devil’s instrument,” used by wandering robbers to sustain their morale or by pimps and prostitutes to entice the unwary. The masinqo, somewhere between the two, is the instrument of traveling professional musicians.What they all have in common, in stark contrast with the courtly instrumentals of Myanmar, is their typical mode of performance: one musician, singing and accompanying himself for a small, intimate audience of family and friends. The songs presented here are almost all vocal, and the lyrics interweave folk proverbs, Bible stories, and the singer’s improvised lyrics to provide a patchwork of lessons and stories for everyday life. Despite their distance from the gilded palaces of Mandalay, listeners will hear in these tracks the same fundamental human concerns as in the Burmese orchestra.

In the slowest and most contemplative of the bägänna pieces, the lyrics are a beautiful series of riddles, puns, and allegories examining the value of mortal life and its relationship to the divine, taken from the Book of Qǝñe, an anthology of Ethiopian proverbs and love poems. The liner notes helpfully explain the wordplay alongside the translation.

This krar piece, performed by Mahay Sofa, was passed down through three generations of krar performers in his family. The lyrics are a mélange of folk tropes, mixing love poetry, pride songs of the Dorze ethnicity, and proverbs. His vocal style, urgently engaged with the emotional fluctuations of the text, must be heard to be believed.

AudioHere the masinqo’s harsh bowed tones blend with a ferocious vocal performance. The effect is well-suited to the brutal war cry of the lyrics. At the conclusion, a percussionist joins and the vocalist breaks into chant for twenty seconds of heart-racing intensity.

Nathan Katkin is a Smithsonian Folkways intern, Columbia University student, and WKCR disc jockey. He plans to major in Classics.

UNESCO Collection Week 58: Lyric, Epic, and Everyday Life in Myanmar and Ethiopia | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings