-

UNESCO Collection Week 61: Ritual Music in Nepal and Around the World

PhD candidate in ethnomusicology and Fulbright scholar Victoria Dalzell explores the nature and beauty of ritual music with this week’s UNESCO releases, Ritual Chant and Music and Nepal: Ritual and Entertainment.

GUEST BLOG

by Victoria Dalzell

When someone utters the term “ritual,” what are the first descriptive words that come to your mind? Maybe “formality” and “solemnity”? Or “complexity”? Perhaps “organized chaos”? This week’s paired albums demonstrate the variety of sounds that exist in the category of ritual.

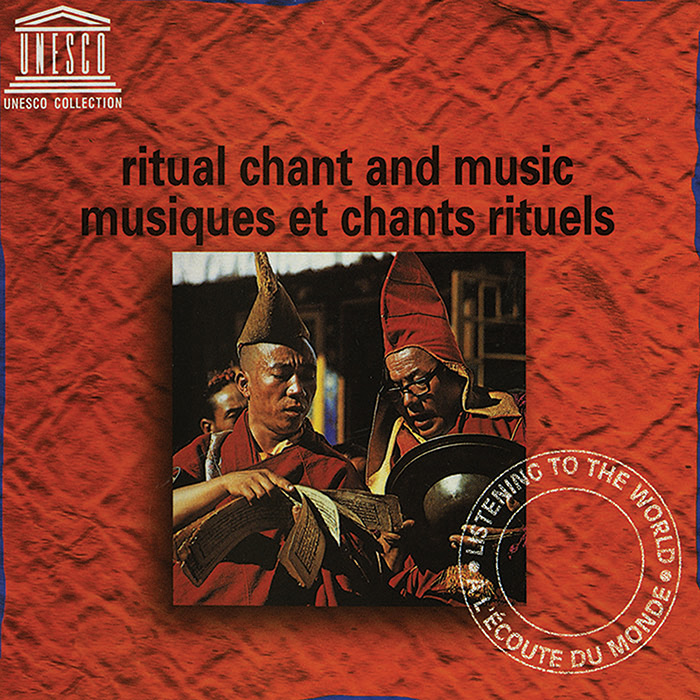

Ritual Chant and Music

The first album, Ritual Chant and Music, includes excerpts from other UNESCO albums, featuring music performed during various ritual events from around the world. These events range from what one might typically think of as ritual—trance and exorcism, liturgy and temple ceremonies, births, weddings, and funerals—to games, healing, and songs of remembrance. Ritual music, as a genre, cannot be defined in terms of certain set musical features, forms, or styles; rather, ritual music is defined by the performer’s intentions. People thus remain central to these musical actions.I found the range of the human voice the most compelling component of this collection. Solomon Islanders and Australian Aborigines tell stories through the very delivery of the narrative, including onomatopoeic words and sounds to animate their scenes. Even in voices which are not “singing,” such as those of the Tibetan Buddhist chanters, a fall and rise and general animation of their voices is present. The Syrian singer’s use of diphthongs, changing the shape of her sound and sliding between the different shapes, adds color to her lines. While many of the Aghanistani na’t singer’s melismatic lines center around different vowels, he bites down on the “m” consonant, providing a contrasting timbre. While I was impressed with the timbral variety of solo vocal performances, I found interactions between multiple voices just as captivating. Consonant harmony between voices features in many of these performances, but so does heterophony (as in the Ukrainian women’s song “Why do you weep, why do you lament?”), and a drone (as in the Armenian men’s song “Ourah ler sourp yeghehetzi,” or “The joy of the Church”).

Many of the recordings featured on this album were made during ritual events, which means that musical sounds are not always the most prominent sounds on the tracks. While a brass band is heard in the background of the recording of the Sicilian Holy Week procession, the call and response of people shouting and playing cymbals and bells, seemingly for the mere pleasure of noise, are foregrounded. Rather than interrupting or intruding on the music, the presence of these other sounds shows that a ritual experience is part of a social fabric and larger sonic environment. While she is specifically speaking about Nepal, anthropologist Chiara Letizia’s observation that “…the presence and visibility of religious communities is not only measured in space (religious sites, processions, etc.) and time (festivals in the calendar) but [is] also a matter of sound” (2012:75) is applicable to many of the ritual situations featured on Ritual Chant and Music.

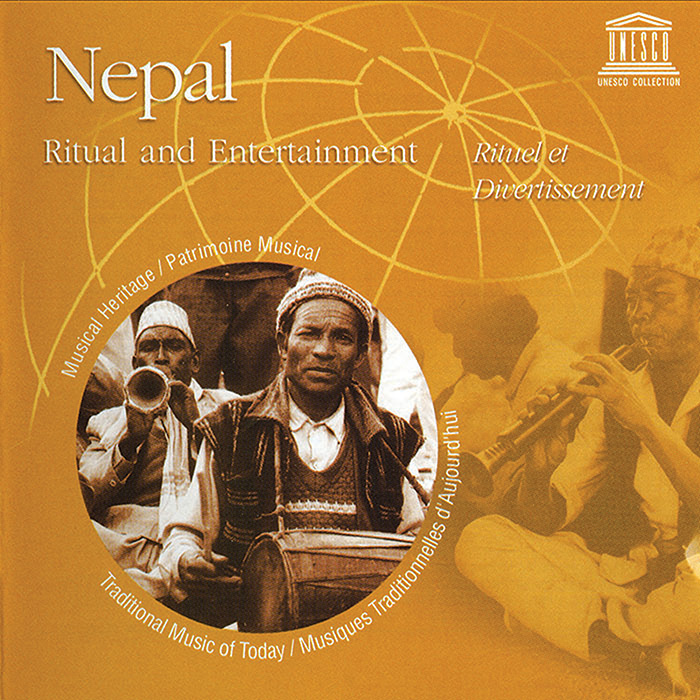

Nepal

On many of the recordings on the second album in this pair, Nepal: Ritual and Entertainment, space and time are brought into being by ritual, musical sound. Through sound, people chart time, name spaces, and create a landscape.In addition to caste groups, including musicians like the Damai and Gaine featured in Tracks 1 through 8 on the album, Nepal is home to 125 known ethnic minorities, of which this anthology features three. These groups hail from places as various as southern Nepal near the Indian border (Tharu), northern Nepal near the Chinese border (Sherpa), and the capital city of Kathmandu (Newar), displaying the sonic diversity which exists within such a small country. Many Newar festivals involve music bands circumambulating through urban spaces, where different melodies are played to invoke deities attached to specific locations on the route. While doing fieldwork in Kathmandu in the fall of 2010, I was regularly awoken at 6AM during the month preceding Dashai (Nepal’s most prominent holiday) by a dhimay band, much like the one featured on the album, passing on the road in front of my guesthouse.

AudioVisiting any temple complex in Kathmandu is an overwhelmingly sonic experience. Devotees ring bells as part of their offerings, music is performed at specific times of day, and these musical sounds mix and mingle with the people’s voices and shuffling feet to create a textured soundscape much like the one at the Manakamana temple heard here:

AudioIn each of these cases, music is not merely a soundtrack to activities; it often structures and constitutes the activities themselves.

When I received the recordings, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that the Tharu were included in this collection. I recently completed my dissertation on Tharu folk music practices. Traditionally, all Tharu performance practices occur in accordance with an agricultural and ritual calendar. In the second year of my fieldwork, one of my interlocutors, Bejlal Chaudhary, literally sang through the Tharu year for me. He performed excerpts of various songs for specific festivals, rituals, life cycle events, work and pleasure, all of which depended on the season of the year. After a group interview in December that focused on the seasonality of Tharu folk songs, one of my interlocutors laughed: “If you sang the sojana [a song for the rainy season, which occurs in August] now, you’ll just look ignorant. Everyone knows that this is the season for damar songs.” One of the songs featured in this album is the festival genre for Maghi. Maghi is the Tharu’s new year celebration, held in mid-January. During the celebration, neighborhood friends form performance troupes according to their generation and go house to house, singing and dancing the maghauta in return for money, alcohol, or festival foods. The call-and-response between the two singing groups is characteristic of not only maghauta songs, but many other Tharu song genres as well, including the magar wedding songs. Listen carefully and you’ll hear a second group of singers repeat the lines sung by the first group of singers.

AudioThe collection of the Nepal recordings is aptly subtitled “Ritual and Entertainment.” While the majority of recordings on this collection are for religious rituals, whose primary audiences are deities, living people make up another important audience. A certain melodic motif or rhythmic pattern may invoke a deity, but musicians provide musical variation and changes in tempo to keep the attention of their human audiences. By participating in ritual events, people enact relationships not only with the sacred, but also with each other, deriving pleasure from creating musical experiences together.

Reference:

Letizia, Chiara. 2012. “Shaping Secularism in Nepal.” European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 39: 66-104.Victoria (Tori) Dalzell is a PhD candidate in ethnomusicology at the University of California Riverside, with research interests in Nepal and the Himalayan region, and ritual, religious and minority music. Her dissertation research focuses on how the Dangaura Tharu--an ethnic and indigenous minority group originally from southwestern Nepal--assert and reify their ethnic identity via music making in light of current ethnic politics in Nepal as well as global support for indigeneity and human rights. She is a Fulbright IIE recipient (2012-2013), and has previously published in the journal Studies in Nepali History and Society (SINHAS). She can be reached at vdalzell@gmail.com

UNESCO Collection Week 61: Ritual Music in Nepal and Around the World | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings