-

UNESCO Collection Week 13: Australian Participatory Music, Two Ways

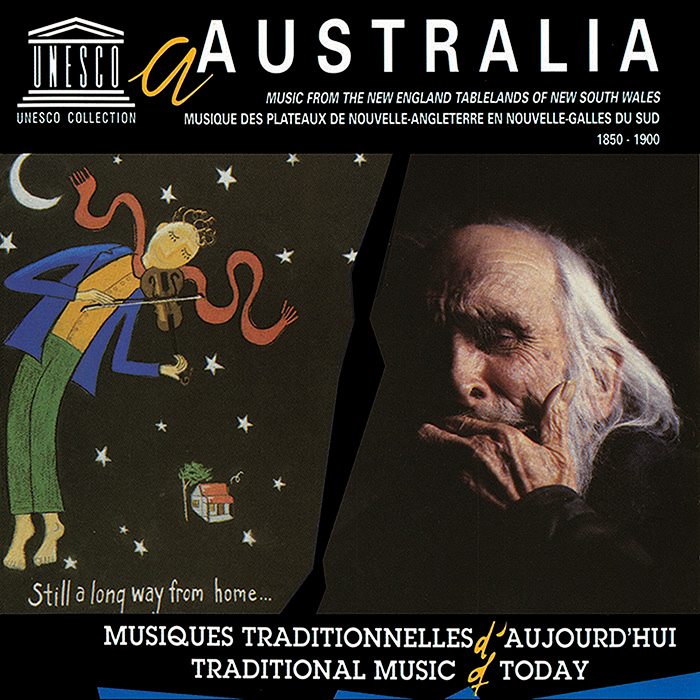

We are now in full swing with the release of the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music via digital download, streaming services, and on-demand physical CDs. Two albums will be released each week, complemented by a guest blog post, until all 127 albums—including 12 that were previously unreleased—become available. This week features two Australian albums, Australia: Aboriginal Music and Australia: Music from the New England Tablelands of New South Wales, 1850–1900.

GUEST BLOG

by Emily Hilliard

My primary framework for understanding Australia: Music from the New England Tablelands of New South Wales, 1850–1900, a collection of modern interpretations of “bush music” dating back to the latter half of the 19th century, largely comes from my own experience playing American old-time music.

Both traditions have origins in English, Scottish, Irish, and other European musical forms, and the two even share some of the same repertoire. “Barbara Allen” (track 13), arranged on this album with vocals, guitar, violin, cello, kendang (a type of skin-head drum), and clapsticks, is also one of the most popular Appalachian ballads in the old-time tradition. “William Grimes the Drover” (track 15) is another classic American folk song and is included in Cecil Sharp’s Appalachian collection.

AudioAnother similarity between American old-time and Australian bush music is that both are participatory forms, played not necessarily for an audience in performative settings, but for dances, house parties, and other social gatherings. In the liner notes of the album, Barry McDonald refers to “the social integration of musical events,” noting that this music “was generally not conceived of outside personal relationship.” Because of the emphasis on participation rather than performance, the bush music collected here is unadorned, without additional value placed on virtuosity.

The instrumentation used in southern American old-time music and Australian bush music differs in some ways. Though fiddle is prominent in both (something I appreciate as a fiddler), the music from New South Wales features accordion and concertina, two instruments rarely heard in old-time, where fiddle and banjo generally take the forefront.

American old-time and Australian bush music were both impacted by other cultures encountered in their respective new homes—but in different ways due to the cultural and geographic settings in which these traditions developed. As emphasized by David Holt in his article ‘Roots of Mountain Music,’ American old-time music was heavily influenced by the vocal styles and rhythms of enslaved peoples from Africa as well as Native Americans 1. As suggested in the liner notes, Australian bush music was greatly influenced by Aboriginal rhythms, instrumentation, and vocal techniques2.This impact often extends to the topical material of some songs. “Dingo Flat” (track 5) is a description of social kangaroo hunting that was an adaptation of local Aboriginal techniques. The liner notes for track 12, a selection of “step tunes,” speak of a musical collaboration on the last song between fiddler Alf Cosgrove and an Aboriginal dancer: “Alf would play this tune for an Aboriginal man, Arthur Widders, who stepped it out on a flattened sheet of bark, ‘rattlin the bones all the while.’ His dancing of the ‘longshoe’ displayed such lightness of step, that he was described by Jim Lowe as ‘a feather with the stem taken out’.”

AudioThough both traditions are carried on today, the cultural context in which the music is played has changed. In both Australia and the United States, social music, formerly a closely shared cultural practice, for the most part has now become much less so, except in a few small, somewhat isolated communities.

Barry McDonald explains, “New Englanders now have widely diverging contacts with music, but few of us experience it as a closely shared cultural process, expressing and reinforcing the most intimate nuances of social life. Still further are we from Aboriginal experience, where the fundamental spiritual expression of the community has always been musical, powerful enough to revivify the very origins of human existence.”

I listened to Australia: Aboriginal Music to better understand some of the Aboriginal influence of Australian bush music, to learn more about the Aboriginal musical tradition itself, and to consider the different sounds that make up the historical soundscape of Australia. The music compiled here is also a social and participatory form, as much of Aboriginal music is. Differing, though, from the collection of songs from New South Wales, this collection represents music from Aboriginal tribes across Australia and emphasizes regional differences and languages.

In general, Aboriginal music is divided into two genres: songs that reinforce social relationships between tribal groups and songs that proclaim the identity of particular groups and their territories. However, much like the songs from New South Wales, these are both community-based musical forms that proclaim a group’s identity and seek to tell its history, values, and belief systems.Most of the songs included on this album are ceremonial songs performed in an open, public forum, and others are performed only in closed ceremonies by and for initiated men. A small selection is played in minor ceremonies by women only. For the recordings on this album, however, all of the songs were performed in public contexts.

Because the major ceremonies predominantly involve men with women assuming a less visible role, men dominate Aboriginal music. Women have a part in larger ceremonies, evident in the “answer” in the call—and—response selection of “Rain Dreaming” (track 1) from the Northern Territory. Women in certain regions also perform love magic rites, wailing, and mourning songs, as in the droning “Women Wu-ungka songs” from North Queensland (track 8).

AudioThough Aboriginal music is largely a vocal form, the most common instruments are simply constructed and made of wood. Some instruments are associated with special rites and are only played during a specific ceremony. The same rhythm sticks from New South Wales bush music are frequently used in Aboriginal music; I would surmise that they are of Aboriginal origin. “Boomerang clapsticks” (paired curve blades) are another common percussive instrument, and lap-slapping and beating sticks on the ground are also typical percussive techniques. The didjeridu or kanbi, as it is known in the Northern Territory, is a long, hollowed branch that is blown with a loose “lip-reed” technique. It is used mainly to enrich the vocal tones, as heard in tracks 1, 4, and 5.

“Balgan songs” (track 4) are communal dance songs from western Australia, sung in the Worora and Wunambul languages and performed by male dancers with clapstick percussion and women beating their laps. “Djabi songs” (track 5) are similar to the ballads in the Australian bush music and American old-time traditions as they are not intended for dancing and are topically about real, non-mythological events. Track 8 also includes a song that feels reminiscent of ballads in the old-time tradition. Similar in subject to the traditional American ballad “Omie Wise” about the drowning of a young girl at the hands of her lover, that selection includes an old story song about two girls who were drowned in the mouth of a nearby river.

Like American old-time and Australian bush music, Aboriginal music has also been heavily influenced by other nearby musical traditions, though, according to author Alice M. Moyle: “From available evidence it would seem that Aboriginal singing styles are more likely to be influenced by other Aboriginal singing styles than by the non-Aboriginal music heard on radios and cassettes.” I do wonder if this has changed since the album appeared in 1992 and modern technologies have become more widespread and readily available.

Though mine was certainly not an exhaustive study, these two albums of distinct traditions of participatory Australian music provide a snapshot of the evolving soundscape of the country. Investigating these recordings as well as their influences and social contexts has informed my own understanding of the genre of participatory music—American old-time—that I’m intimately familiar with as a musician and listener.

Emily Hilliard, Washington, D.C.

Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, customer service representative

Folklorist, performs old-time fiddle and writes the pie blog Nothing in the House

Instagram @thehousepie.

1 David Holter “Roots of Mountain Music”

2 Alice M. Moyle Liner notes, Australia: Aboriginal Music. UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1977, compact disc.

UNESCO Collection Week 13: Australian Participatory Music, Two Ways | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings