-

UNESCO Collection Week 19: Perspectives on Vietnam and Bali

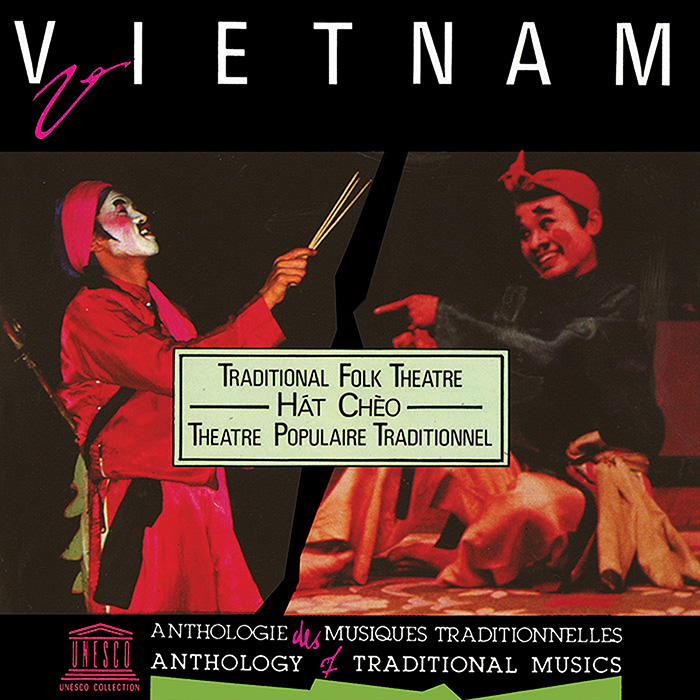

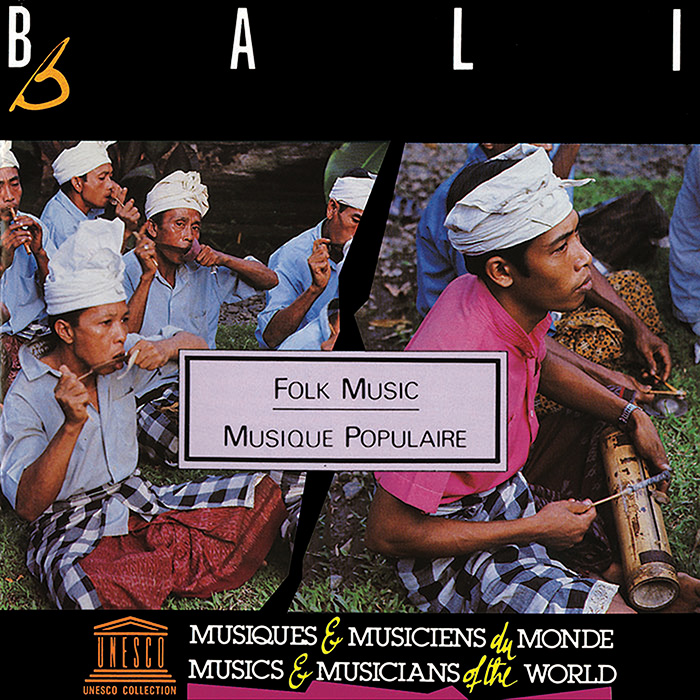

Week 19 celebrates Vietnam’s National Day on September 2 with an album of Vietnamese traditional satirical theatre music, Vietnam: Hát Chèo – Traditional Folk Theatre. Later this month, Bali will celebrate Tumpek Wayang, a ceremony in which the Balinese bless their wayang kulit (shadow puppets). The other recording reissued this week, Bali: Folk Music, includes music from the shadow puppet theatre.

GUEST BLOG

by René Van Peer

How much can perspective shift in 40 years? That question goes around in my mind when writing about Vietnam: Hát Chèo – Traditional Folk Theatre (recordings made in the northern part of Vietnam) and Bali: Folk Music. Both of the recordings were made in the 1970s and first released in the 1980s. Produced with the stamp of UNESCO, albums such as these carry a certain degree of authority.

There is a marked difference in presentation between the two albums, possibly dictated by the political sensitivities of those times. The liner notes to the hát chèo recording tell how this ”popular satirical” folk theater genre, which “stands for the more humble against the injustice and oppression of the more powerful” (including a clown making fun of ”important people”), went through a revival after the August Revolution.The August Revolution led to the declaration of an independent Vietnam by Ho Chi Minh in 1945 to end centuries of French imperial rule. This conflict preceded the Vietnam War, in which the North Vietnamese underdogs fought against the “powerful”—first France, then the United States. That seems to resonate with the hát chèo genre, especially because it originated in the rural north of the country, the heartland of the Vietcong. Small wonder then that it became so popular in the decades of struggle.

This album was made in collaboration with the state-sponsored Institute of Musicology and the Composer’s Union of Socialist Republic of Vietnam.1 With that in mind, one becomes curious about the context and contents of each single track, whether they have any bearing on the situation in the country at the time or reflect it in any way. The liner notes provide only a general description for the styles of declamation of the songs in relation to the role of the characters, whereas there is no translation of the lyrics or overall idea of the plays from which these fragments were taken. It is not clear whether the texts—declaimed and sung to an ensemble of flutes, bowed and plucked strings, and percussion—have been handed down the generations virtually unaltered (comparable to Japanese Noh pieces) or whether they include topical storylines and themes built around the traditional framework and characters. What exists is a carefully executed set of twelve pieces in gloriously claustrophobic mono, stars scintillating in splendid isolation.

Bali: Folk Music provides a rather different picture. According to the liner notes, all six tracks share a similar division of labor in the music: melodic and rhythmic patterns are woven together by the individual members of ensembles, regardless of whether they are vocalists (as in the lengthy theatrical Tjak performance that opens the album) or instrumentalists (as in an exquisite Gandrangan court music piece).These patterns underpin captivating melodies, solo or in alternating duet. This basic structure generates a staggering diversity of pieces played by village musicians. In comparison with the rather more constrained and studied Vietnamese hát chèo fragments, the Balinese music is exhilarating and joyous, full of flashing color.

AudioSuch exuberance breathes a spirit of freedom that is mirrored in the accompanying texts. The dates and origins of these pieces are clearly explained in the liner notes. Musically, there is a fleeting quality that seems to contradict the steadfastness of the pulse and the confidence of the collective virtuosity.

AudioBoth albums are snapshots that reflect realities and perspectives of the period in which they were taken. Both carry that proud UNESCO seal of approval. Whereas one shines with irrepressible clarity, the other seems secretive and subdued. Seemingly, they contrast like open air and closed space. One can only wonder: how much has the musical scenery changed in 40 years? And how do specialists now view and amend the information surrounding the music? If change is stifled, the spirit is choked—and life evaporates.

René van Peer is a Dutch music journalist who writes about non-mainstream music for newspapers and magazines, and has produced broadcasts for national radio in the Netherlands.

1 Tran Van Khe, Liner Notes, Hát Chèo: Traditional Folk Theatre, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1989, compact disc, p. 4.

UNESCO Collection Week 19: Perspectives on Vietnam and Bali | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings