-

UNESCO Collection Week 25: Musical Treasures from Oman and Yemen

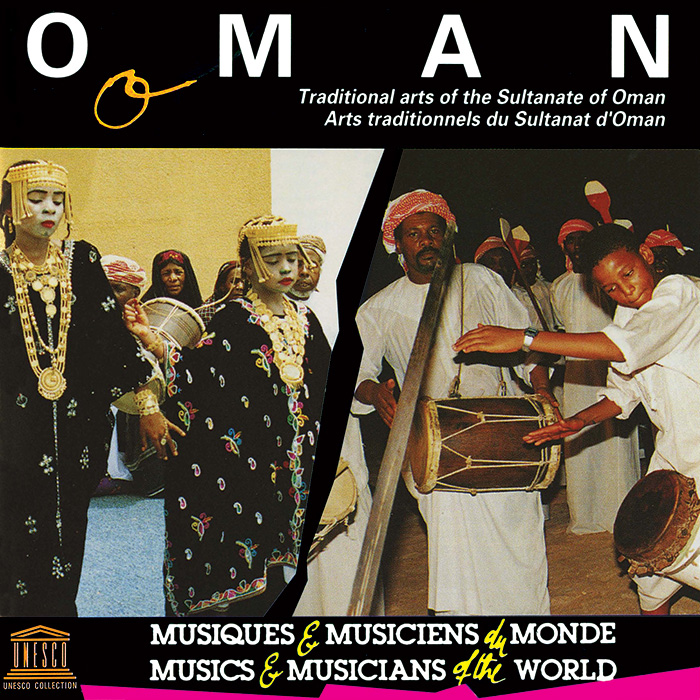

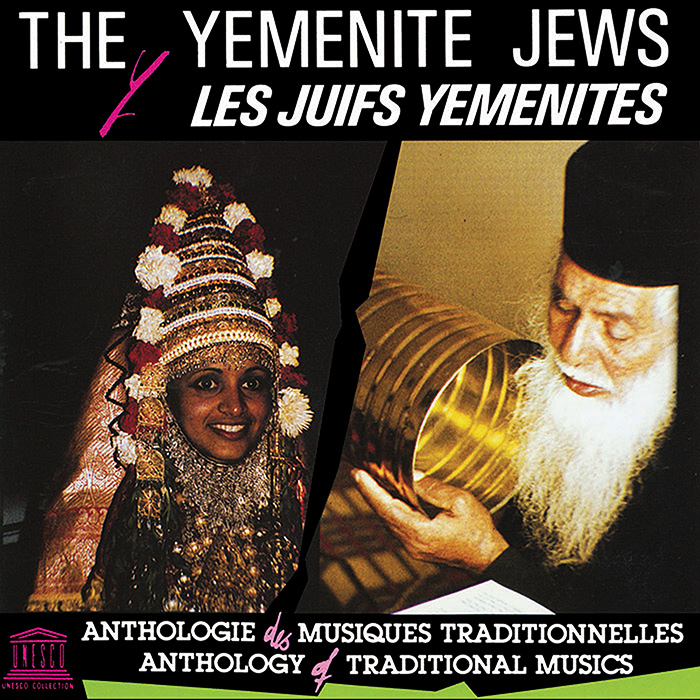

In celebration of Yemen’s Liberation Day on October 14, The Yemenite Jews is one of this week’s UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music releases.The other release is Oman: Traditional Arts of the Sultanate of Oman, which reflects the bordering nation’s Arabic, African, and Asian influences.

GUEST BLOG

by Alan Núñez

Everyone who loves music can think of a special time when a song seems to capture the imagination at first listen. The rest of the album can be great or not, but either way, you find yourself going back to that one track. For those who have experience with LPs, 8-tracks, and cassettes, this is the time when catastrophe might strike; the medium weakens from constant use. For better or worse, CDs and digital files don’t seem to have that characteristic.

I had this experience when listening to these two albums, as they both contain at least one track that my finger kept clicking back to repeatedly. The track “Malid,” heard about halfway through Oman: Traditional Arts of the Sultanate of Oman, was the first to hit me in this way. In the middle of the song, I heard a complete fasi, a section or chapter of the elaborate celebration of the Prophet Muhammad, and the rhythmic chanting of these men became a transcendent aural journey. With a percussive element used so sparingly as to make you think you might have dropped your iPod, these voices form a concert which seems to alternate between polyphony and canon.As with so many of the UNESCO releases, this album contains a vivid cross-section of both liturgical and secular forms, as well as a variety of instrumentation. This variety is particularly welcome in the case of Oman, which I think can claim a much greater spectrum of cultural diversity than other Arab Gulf States. Historically, its influence expanded from the Indian Ocean to East Africa toward Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania. This geographical network is aurally communicated in the African drums that form the backbone of “Tamburah,” a meditation on the lyre, and “Shubani,” a sailors’ work song.

Members of the Jewish faith are referred to as “people of the Book,” and the “Book” is often masterfully sung in addition to being spoken. The Yemenite Jews does a wonderful job of showing why the contribution of Yemenite Jewish culture to this practice cannot be overstated. Several of these tracks are part of the dazzling tradition of the diwan, a collection of poetic musings on secular and religious themes that are often sung or chanted. A Persian word for “list” or “register,” diwan captures the air that exists between the threads of religious and secular life.The selection that captured me from the first long vocal phrase was the masterpiece “Yashqef Elohim Mi-Me’On Qodsho.” The story, which tells of God’s revenge on the enemies of His people, is represented by the pulsating and seemingly never-ending vibrato found within the nashid, or introductory section. This segues into a song whose propulsion seems to come from what can only be described as sounding like a metal trash can. I say this with great love and admiration, as the best musicians I know use just such musical tools. In the case of this recording, it highlights the fact that after the destruction of the Temple, musical instruments were forbidden, and these percussive elements were—thankfully in my view—not banned for being “musical” objects.

The overall beauty of music is that it is a social conceit, a necessity for many of us. The performance, composition, and listening binds us together. It should not be surprising that a number of these treasures were recorded during weddings and other communal ceremonies. We have much for which to be grateful to Smithsonian Folkways, and we should add these newly re-released albums of UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music recordings to that list. The beauty of these two countries and traditions, which are so close physically but so diverse culturally, has rarely been so evident.

Alan Núñez is an educator, musician, digital media guy, and certified barbecue judge and competitor. He has worked as a teaching artist in New York City schools for more than fifteen years. He is now the music teacher for Academy of the City Charter School, a progressive charter school in Woodside, Queens.

UNESCO Collection Week 25: Musical Treasures from Oman and Yemen | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings