-

UNESCO Collection Week 29: Transcending Borders - The Music of Thailand and Laos

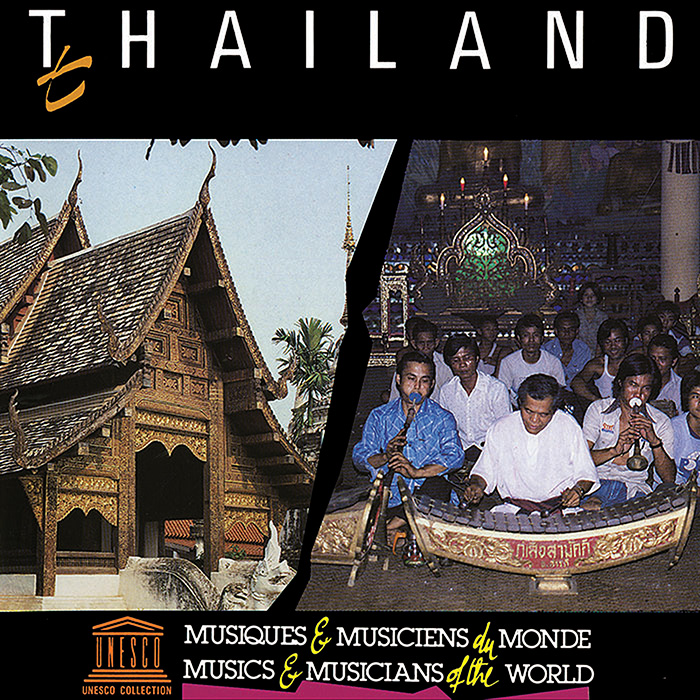

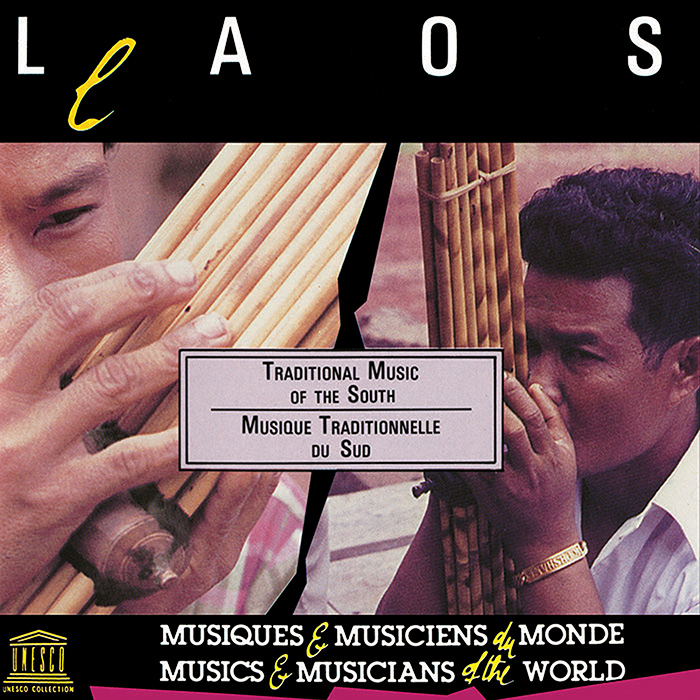

The two UNESCO releases for this week, Thailand: Music of Chieng Mai and Laos: Traditional Music of the South, challenge our understanding of how culture is spread across nation boundaries, and suggest that the culture of the “highlanders” of Southeast Asia may be more transnational than expected.

GUEST BLOG

by Sam Cartmell

The history of Southeast Asia (and its music) is often told through the rise and fall of its Kingdoms – usually lowland city-states with economies and military power based on sedentary paddy rice cultivation.1 Yet daily life for a great number of people living in the highlands of the region was based on small-scale shifting cultivation, and paying (or avoiding paying) tribute to whichever Kingdom happened to be nearby.2 The recordings on Thailand: Music of Chieng Mai and Laos: Traditional Music of the South represent the royal court traditions as well as those of more "humble" origins. Taken together they reveal some of the tension and intermingling between the different traditions of “lowlanders” and “highlanders.”3

In the fields of anthropology and political geography, James C. Scott and others have recently argued for the concept of “Zomia” in order to shift focus to the underrepresented “highlanders” as important political and cultural actors. They have conceptualized “Zomia” as a geographic region consisting of highland areas in India and China as well as parts of every mainland Southeast Asian country except Malaysia. In opposition to the common understanding that hill peoples were "left behind," Scott argues that the peoples of Zomia intentionally lived in parallel or even in a state of perpetual flight from the ills of the lowland Kingdoms – namely slavery, tribute extraction and military conscription. Zomia can be considered “not simply a space of political resistance but also a zone of cultural refusal.”4 The concept of Zomia also has implications for our understanding of this region’s cultural development, and provides a novel way to examine the development of its music.These two titles from the UNESCO collection both highlight different strands of “highlander” and “lowlander” musical traditions in the region, as well as point to potential areas of overlap between these arbitrary categories. Thailand: Music of Chieng Mai has a strong focus on musical traditions coming out of the royal court: Thai pinphat and Khmer pinpeat orchestras. On the other hand, Laos: Traditional Music of the South focuses more on musical styles and themes closer to the lives of ordinary people: the seemingly less-structured singing and driving rhythms of “Music for the ceremony of the buffalo sacrifice,” and the shamanic trance-inducing khene (a mouth organ of Lao origin made of seven pairs of bamboo tubes) drone of “Pheng Phi Fa.” That being said, songs and melodies are also commonly shared across political and geographic borders. It is possible that “Lot Fay Tay Lang”(“Train goes down the track”), found on Laos: Traditional Music of the South, originated in Thailand because Laos has never had much railway coverage; prior to the turn of the 21st century, only seven kilometers of railway track had ever been built in Laos. Instruments are also shared across musical boundaries: on “Pheng Soysonthat” we hear the Champassak orchestra playing pinphat-influenced music but with the khene firmly out-front.The khene is a good example of the persistence of musical forms originating outside of the region's royal court culture. The exact origin of the instrument is not known, but it dates at least several thousand years ago. A number of ethnic groups across Southeast Asia have traditional instruments which are variations of the khene – such as the Hmong Qeej, the Lisu Fulu, the Lahu Naw, and many others.

The aim of a khene player is to produce a continuously fluctuating drone by alternately blocking and unblocking holes drilled into the bamboo tubes. Jaron Lanier, a technologist philosopher, has called the khene the first digital instrument: the first, he argues, due to its being thirteen thousand years old and its use of parallel off/on settings to produce sound.6

The khene is a key element in the style of music widely known as Mo Lam. The lyrics of Mo Lam music are loosely composed in regular stanzas and are usually based on well-known stories or poems, but lyrical improvisation is encouraged. Much Mo Lam is done in male-female courting repartee which often uses humorous innuendo. This type of song can be heard on “Lam Sithandone,” performed by Thao and Nang Sikhone. The trend towards improvisation also allows the Mo Lam singer to speak on current events and engage in social commentary. Both biting political critique and government propaganda have appeared in Mo Lam performances.

While Mo Lam remains a popular music form in Laos and Thailand to this day, modern forms of Mo Lam called Mo Lam Sing – from the English word "racing" –typically replace the khene with a synthesizer or, if a real khene is used, it takes a supporting role to contemporary "rock" instruments. To my ears much of the soul of Mo Lam is lost with this replacement, and I prefer the older forms of popular Mo Lam where the khene is front and center.

Sam Cartmell co-founded and regularly contributes to The Archive of Southeast Asian Music.

1 Thongchai Winichakul. Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994. Print.

2 James C. Scott. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. Print.

3 Craig A. Lockard. Dance of Life: Popular Music and Politics in Southeast Asia. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1998. Print.

4 Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. Print.

5Rob Robinson. The Only Railway (Ever) in Laos. The International Steam Pages. Web. 6 October 2014.

6 Layar – Jaron Lanier at ARE 2011. Youtube.

UNESCO Collection Week 29: Transcending Borders - The Music of Thailand and Laos | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings