-

UNESCO Collection Week 38: Sounds of the Middle East—Past and Present

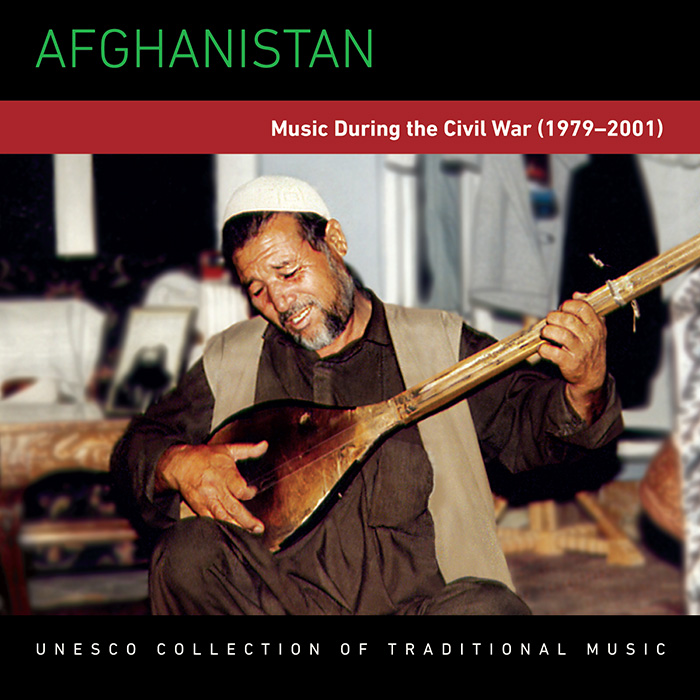

This week’s UNESCO releases, Turkish Classical Music: Tribute to Yunus Emre and Afghanistan: Music During the Civil War (1979-2001), offer two diverse soundscapes from the Middle East. The former features the National Choir of Turkish Classical Music, and honors the memory of 13th century poet and humanitarian Yunus Emre. The later, which presents the music of persecuted musicians, is one of twelve previously unreleased albums from the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music.

GUEST BLOG

by Holly Hobbs

Turkish Classical Music: Tribute to Yunus Emre honors the memory of Yunus Emre—13th century epic poet, Sufi mystic, and humanitarian—through song. A contemporary of the more widely known Rumi, Yunus Emre’s life remains mostly shrouded in mystery, in keeping with his now-mythic status in Anatolia. His epic songs, which dealt with themes of spirituality, social uplift, and philosophical introspection, continue to influence modern poets, composers, and musicologists today. Recorded in 1991 to mark the 750th anniversary of Emre’s birth, this albumfeatures the National Choir of Turkish Classical Music under the direction of Dr. Nevzad Atlığ interpreting works by 14th to 19th century Turkish composers, whose music survives in manuscript form. Insightful liner notes by the renowned Turkish scholar and musicologist, Yilmaz Öztuna, round out the experience of the album. Although Turkish Classical Music stands alone as a masterful work based on performance, it also works on a number of other levels: an homage to a seminal cultural figure and an interpretation of a musical soundscape of another age.The forms of music-making that have come to be termed “Turkish art music” are rich musical traditions born out of the Ottoman Empire that draw upon culturally informed makams for their content and structure.Much like the Indian raga, Turkish makams are a complex, mutable system of rules that loosely govern scales, progressions (seyir), modulation (çesni), and so on. According to Sufi teachings, specific makamscan be linked to various stages of enlightenment. While hundreds of makams were in practice centuries ago, far fewer are in active use today.

Influenced by the teachings of the mystical orders of Islam that existed within the Ottoman Empire as well as by Arab, Iranian, Greek, Armenian, and Jewish traditions, Turkish classical music is introspective, meditative, and melodic, often marked by long, extended passages that build to multiple crescendos. Based on music theory that dates back at least a thousand years, Turkish art music is a modal musical tradition that privileges melody over rhythm. This recordingtends toward a fluid approach to time signature and rhythm, in parts leaning toward free time or senza misura. String and wind instruments support the lush choral melodic lines, and a consistent tonal center sonically illustrates the makam-derived structure.

I’ve chosen to highlight the 10th track, “Çin-i giysusuna zehcîr-î teselsül dediler,” because it encapsulates many of the sonic themes of the album. Beginning with a melody line performed by stringed instruments (çeng, kanun) doubled by pan-flutes (miskal) and played within a largely chromatic scale, the extended instrumental introduction sets the tone for the choral exposition. No harmony appears here, as voices and instruments separated by octaves sing and play in unison on the same melodic line. The result is a fascinating and singular acoustic experience, made all the more aurally interesting by the use of close seconds and hints of semitones. Ornamentation and melismatic singing are always interesting to me, but in the context of this album, recorded as it was with excellent acoustics and a slight reverberation, the result is hauntingly memorable.

Turkish Classical Music: Tribute to Yunus Emre stands as a beautiful homage to a poet who should be remembered and as a fascinating listen into Turkish cultural aesthetics.

Recorded in 1996 in the midst of ongoing civil war and persecution of Afghani musicians, Afghanistan: Music During the Civil War (1979-2001) stands as a testament to the will of a people and the power of art. A rare gem, this album is one of twelve previously unreleased albums by the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music in conjunction with Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Afghanistan’s geostrategic position was far more a curse than an advantage. British imperialism, colonial interventions, and ongoing ethnic conflicts paved the way for the decades of extreme violence and unrest between 1979, which marked the invasion by the former Soviet Union, and September 11, 2001, the date that would change the course of Afghani modern history forever. Communist rule by the former Soviet Union lasted through the late 1980s, followed by the Afghani Civil War (1989-1992), the founding of the Islamic State of Afghanistan in 1992, and the rise of the Taliban in the mid-1990s. As is now widely known, various foreign governments, including the U.S., Pakistan, China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, all took sides, aiding the mujahideen (guerrilla forces that opposed Soviet forces)or the former U.S.S.R., respectively. The global Cold War was played out on the battleground of Afghanistan, with the Afghani people bearing an enormous share of suffering. As early as 1985, half of the Afghani population was estimated to be displaced by war.

Alongside continued upheaval, violence, and displacement, both the Soviet occupation and the Taliban regime severely restricted artistic and cultural expression in Afghanistan, and public music performances were generally only allowed in the Northern provinces. Extreme censorship meant that musicians’ lives were often in peril, and far too many artists lost their lives to ignorance. Many fled to the West, or to the neighboring countries of Pakistan and Iran. Everything from the construction of musical instruments to traditional systems of music education and apprenticeship, recording, and performing were severely impeded. As the liner notes tell us, this was memorably illustrated by the bombing of Kucheh Kharabat in Kabul, where most well-known musicians in the area resided—engagement in the arts was viewed as a threat to social control. By 1996, the year this album was recorded, the Taliban had taken control over Kabul, which in turn led to a total ban on music in many parts of the country. Instruments were destroyed, lives were lost, and, without their livelihood, many musicians were forced to flee to refugee camps or to beg on the streets.

Traditional Afghani music can, generally speaking, be divided into two loose categories: classical and folk. This recording falls into the folk music category (musiqi mahallí). Instruments here are subordinate and largely serve as accompaniment for the vocals, which are highlighted both sonically and dynamically. The Dutch musicologist Jan van Belle, who wrote the liner notes to the album (he also recorded and produced it), writes that some songs on the record are specified according to their region or their connection with domestic activities or festivities, like wedding songs (âhang-e arusî) and lullabies (lala’ík), while others come from the oral epic traditions. Double and triple rhythms are common, and the music’s emphasis on dance is immediately apparent.

The track I’ve chosen to feature, “Henâ beyârid” (“Bring the Henna”), was recorded in the music department of Radio Afghanistan in Kabul, which had over the years fallen into a state of neglect and disrepair. Radio Afghanistan was one of the many private locations in Kabul that had to be used to discreetly record songs for this album. As Jan van Belle tells us, most of the players on this track were professional musicians who were once employed by Radio Kabul.

While many tracks on this beautiful album stand out, focusing on a track secretly recorded in Kabul, ground zero for the occupation of Afghanistan, seemed to me to be particularly illustrative of the power and importance of this record. The subject matter was of significance as well: a song traditionally performed in happier times, “Henâ beyârid” celebrates the tradition of ritually adorning women’s hands and feet with henna on occasions of community celebration. Jubilant and celebratory, “Henâ beyârid” and the other tracks on this rare album defy oppression and assert indigenous cultural pride and beauty in the face of unspeakable violence and destruction.

Holly Hobbs is a PhD candidate in ethnomusicology at Tulane and the founder/director of the NOLA Hip-hop Archive, a digital archive of hip-hop oral histories housed at New Orleans’ Amistad Research Center. Hobbs has researched and written on grassroots music traditions in the American South, the west of Ireland, and East Africa. She currently writes for KnowLA: the online encyclopedia of Louisiana Music and Culture, Music Rising, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music via Smithsonian Folkways, and the urban music and culture website, The Smoking Section.

UNESCO Collection Week 38: Sounds of the Middle East—Past and Present | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings