-

UNESCO Collection Week 39: Music from the Arabian Gulf

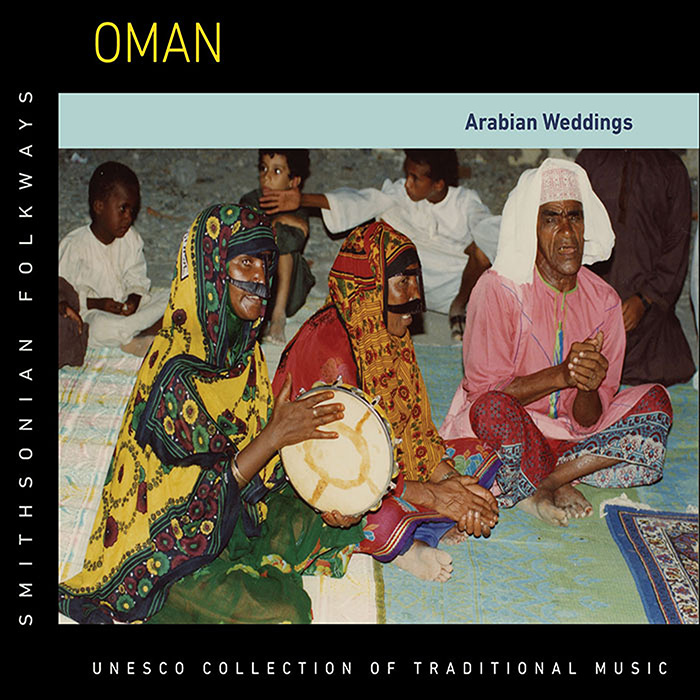

To honor the Muscat Festival, which takes places in Oman from January 15 to February 14 to celebrate Omani culture and arts, this week’s UNESCO release is the previously unreleased Oman: Arabian Weddings. Paired with this album is neighboring Yemen: Traditional Music of the North, which reflectsa wide variety of musical influences, illustrating the country’s unique geographical location between Africa and the Middle East.

GUEST BLOG

By Anne K. Rasmussen

Yemen: Traditional Music of the North and Oman: Arabian Weddings, originally produced by the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, offer some of the most distinctive performances of the Arab world and Indian Ocean region. The recordings and documentary notes from northern Yemen were made by Christian Poché, the esteemed musicologist of the Arab world and Middle East region. The previously unreleased Omani recordings, all from the northern coastal city of Sohar in the Batinah region, are the result of team research carried out in the early 1990s by ethnomusicologists Dieter Christensen and Salwa El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, with assistance by Khalfan Barwani, then director of the Oman Center for Traditional Music in Muscat. Both recordings represent the cooperative efforts of government organizations with European and North American researchers, and both recordings reflect the proactive efforts of the Yemeni and Omani people to collect, document, preserve, and promote the rich and diverse music, dance, and ritual cultures of their respective regions.

Yemen, and Oman are neighboring countries located on the Arabian Peninsula, and as such, they share many traditions that are unique to the Gulf, and to the Arab world. Both countries experience the seasonal monsoon (khareef), which brings them rain, mist, and rich green vegetation when most of the peninsula is unbearably hot and dry. The most ancient and active maritime trade routes are located along their coasts. To the historic transcontinental demand for everything from frankincense, pearls, slaves, dates, and wood, are now added all manner of material goods and commodities, ensuring the significance of these Indian Ocean nations in a modern, global world. In spite of their strategic position in this globalized economy, their music reflects traditional environmental contexts and the special relationships between various ethnic and social communities.

The liner notes for Oman: Arabian Weddings, written by Christensen, derive from as well as expand upon the musical ethnography of Sohar. A unique aspect of Christensen and Castelo-Branco's teamwork is the documentation of both men’s and women’s music and activities, a balance that was afforded by this co-ed research team, with the help of Barwani, their local guide.To contextualize the music of Arabian weddings, Christensen presents a normative account of a traditional five-day wedding celebration. Scholars of the Arab and Islamicate world and Middle East region will be especially interested in the rich descriptions of the various troupes of musicians who perform over the course of the event, as well as in the activities of both men and women in the wedding party. Ritual henna songs sung by female attendants of the bride (track 2), as well as ghina nisa’ sung by hired professionals (track 3), offer a sound-print of women’s musical contribution to this most significant event in the lives of Omani families.

AudioAs with most of the vocal music, these songs are responsorial. A notable performance practice is the doubling of the solo “call” by a singer’s assistant, which we can hear on track 6, where Halimah, the lead singer, is supported by her sister. The syllables they sing repeatedly, “dana dana, yo dani dan,” etc., are common not only to this “folkloric” music, but also to the refrains of much of the contemporary music of the Gulf. Such popular music is heard and emulated across the Indian Ocean region and performed in places as far-flung as Indonesia, where many forms of music from Oman and Yemen have taken root.1

The live ambiance of field recording renders palpable the excitement of the zaffa (traditional wedding procession), where musicians, dancers, and celebrants process and present the bride and groom individually and in some cases, as a couple (track 9). This procession of the groom (zaffat al-mu’aris)begins with a halqat al-malid, the zikr-like religious ritual where a robust chorus sings songs of praise to the Prophet Muhammad while performing interlocking patterns on various frame drums.

Dān group performing ghinā‘ nisā‘, woman's songs during a procession for washing the groom. The lead singer uses a bullhorn. Sohar, July 1995.

All of the genres featured on Oman can be witnessed outside the context of weddings during annual festivals, where they are re-contextualized for local and tourist audiences. Often taking the guise of staged weddings and village celebrations, ghina nisa’ (women’s music), lewah (an Afro-Omani music for healing and trance), and zaffat al-mu‘aris, are re-presented in festival contexts and for national television. Regional musical genres, originally codified in the 1980s by the Oman Center for Traditional Music,2 are perpetually patronized and broadcast nightly during the Muscat and Salalah festivals that occur during winter and summer months, respectively, and for events such as National Day.

Oman is known as a cultural crossroads whose arts are indebted to Arab, Indian, Persian, and African influences; however, many artists acknowledge Yemen as the true fount of the Arabian musical practices.3 Yemen: Traditional Music of the North features a collection of performances from Kawkaban, “a fairyland hamlet at 2,000 meters elevation that, along with the cities of Ibb and Menaka, is the artistic cradle of Yemen.”4 Poche’s notes rightly point out that music in Yemen, as in Oman, stands apart from the Ottoman-Arab maqam traditions of the Silk Road regions of Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean, where a family of musical instruments of complementary timbres (the oud, qanun, nay, kamanja and various percussion) perform repertoire, both composed and improvised, according to a sophisticated and actively theorized complex of musical modes. Rather, in Yemen, poetry (track 2), responsorial singing (tracks 4 and 7), and solo or paired instruments comprise traditional music making in much of the Gulf as is exemplified in these rare recordings collected during Poche’s 1975 expedition.AudioTracks 1 and 10 on Yemen feature the flute, gasba, in duet. Continuous variation of melodic motifs within in a limited range, and polyrhythmic shifts in accent suggest the influence of musical principles frequently heard in African traditional musics. The zar (track 3), a ritual for spiritual transcendence and healing, performed on the tanbura, a lyre whose iconographic representations date to the times of the Pharaohs, is a fantastic example of a practice that is widely dispersed in Africa, Egypt and throughout the Gulf, but rarely heard except in public, folklorized performances.

These two recordings are thrilling representations of the exceptional music from the Arabian Gulf. The recordings also reflect the concerns of ethnomusicologists whose work is separated by more than two decades: Poché’s notes highlight nomenclature and organology, along with formal and tonal analysis, whereas Christensen, along with El-Shawan Castelo-Branco and Barwani, was more interested in social context and the professional (or amateur) lives of musical specialists. I encourage all music enthusiasts and explorers to give these two albums their attention.

Anne K. Rasmussen is professor of Music and Ethnomusicology, and the Bickers Professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the College of William and Mary where she also directs the Middle Eastern Music Ensemble. Rasmussen’s research interests include music of the Arab and Islamicate world, music and multiculturalism in the United States, music patronage and politics, issues of orientalism, nationalism, and gender in music, fieldwork, music performance, and the ethnographic method. She is author of Women, the Recited Qur’an and Islamic Music in Indonesia (2010); co-editor with David Harnish of Divine Inspirations: Music and Islam in Indonesia (2011), co-editor with Kip Lornell of The Music of Multicultural America (1997, 2015), and editor of a special issue of The World of Music on “The Music of Oman” (2012). Rasmussen’s interest in the Gulf region has been enhanced by her fieldwork, beginning in 2010-11, in the Sultanate of Oman, when she was Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center Research Fellow.

References Cited

Al-Harthy, Majid and Anne K. Rasmussen. 2012. “Music in Oman: An Overture.” The World of Music New Series 1/2: 9-43

Christensen, Dieter and Salwa El-Shawan Castelo-Branco. 2009. Traditional Arts in Southern Arabia – Music and Society in Sohar, Sultanate of Oman. Berlin: VWB – Verlag fur Wissenschaft und Bildung

Harnish, David, and Anne K. Rasmussen, eds. 2011. Divine Inspirations: Music and Islam in Indonesia. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

Rasmussen, Anne K. 2010. Women’s Voices, the Recited Qur’an, and Islamic Music in Indonesia. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Rasmussen, Anne K. 2012. “The Musical Design of National Space and Time in Oman.” The World of Music New Series 1/2: 63-97.1 See works by Rasmussen (2010) and Harnish and Rasmussen (2012) for more on Indian Ocean Islamic traditions in Indonesia.

2 For more on the national initiatives to preserve and present music in Oman see works by Rasmussen (2012), and Al-Harthy and Rasmussen (2012). See also the website for the Oman Center for Traditional Music.

4 Christian Poché, liner notes to Yemen: Traditional Music of the North, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1988, compact disc.

UNESCO Collection Week 39: Music from the Arabian Gulf | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings