-

UNESCO Collection Week 41: Global Sounds of Love and Loss

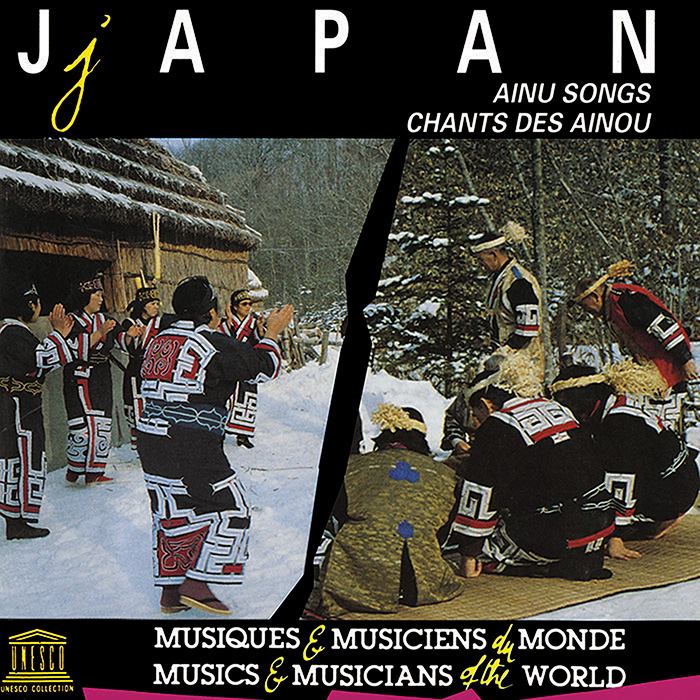

This week millions of people around the globe will celebrate Valentine’s Day. Evidence of Valentine’s greetings date back to the Middle Ages; the holiday, whose origins are somewhat mysterious, contains elements of both Christian and ancient Roman traditions, with connections to St. Valentine and the pagan festival Lupercalia. This week’s UNESCO compilation Love Songs offers musical expressions of love from around the world. Paired with this release is Japan: Ainu Songs, which features music from a culture in danger of losing its identity.

GUEST BLOG

by Stephanie K. Andrews

During the process of researching master’s programs in ethnomusicology, I have thoroughly enjoyed listening to the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music. The extensive collection has broadened my worldview and added new favorites to my once limited personal catalogue. I have particularly enjoyed listening to the compilation albums, which enable me to digest a wide variety of world music in a single listen. For this reason, I’m sharing Love Songs, a compilation featuring 17 countries and musical traditions, including a wedding dance from Oman, a mourning song from Hong Kong, an ancestor worship song from the Central African Republic, and a comedic love song from Belarus.

Audio

During the process of researching master’s programs in ethnomusicology, I have thoroughly enjoyed listening to the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music. The extensive collection has broadened my worldview and added new favorites to my once limited personal catalogue. I have particularly enjoyed listening to the compilation albums, which enable me to digest a wide variety of world music in a single listen. For this reason, I’m sharing Love Songs, a compilation featuring 17 countries and musical traditions, including a wedding dance from Oman, a mourning song from Hong Kong, an ancestor worship song from the Central African Republic, and a comedic love song from Belarus.

AudioAs a fiddle player, I found myself drawn to track 12 (“Homslien, gangar”), a Norwegian tune for hardingfele—a traditional fiddle with four strings like the violin and four or five sympathetic strings. The hardingfele provides a fuller sound, with the sympathetic strings creating a drone on the tonic under the four bowed strings. The song is a gangar (walking dance) in 6/8 time from Austegard, sung to a young shepherdess by goblins. The song utilizes a special tuning called “goblin” tuning, which emphasizes the playfulness of the song by creating a bright, open sound. The inclusion of this goblin tune indicates that the theme of love was as prevalent in ancient folklore as it is in modern popular culture.

The playfulness of the hardingfele is completely abandoned as the next track presents a Portuguese fado—a genre of music recognized by its often mournful melodies and lyrics—about lost love. Though some might consider the transition jarring, this variety is what I enjoy most about the album: every song disrupts the listener’s expectations as each recording exhibits a different tradition and story about love or loss. Among these are the mazoma, a dance performed by men in Malawi to demonstrate their strength, and the lam, a Laotian style of courtship song that requires highly skilled singers. This recording broadens our American ideals of love by examining how other cultures express courtship, marriage, and mourning through song, while also exposing the listener to many global music traditions.

AudioTrack 4 (“Chisi-sinotcha”) features a song from the Ainu people about heartbreak, in which the female performers often cry while singing. The Ainu are regarded as a “mystery race,” indigenous to the northern islands of Japan, whose language and religious rituals bear little resemblance to those of mainland Japan. Singing makes up a large part of their musical tradition and is closely linked to their tribal lifestyle and religion, which is based on animism and shamanism. Their melodies are loosely structured around a pentatonic scale, though many songs only use two or three notes. Before I listened to Love Songs, I was not familiar with the Ainu people, but the haunting nature of the singer’s vibrato inspired me to learn more about their culture and musical traditions, featured on the UNESCO album Japan: Ainu Songs.

As a German-American, it isn’t difficult to connect with my heritage. Whether it’s Beethoven’s Fifth at the local symphony, shopping for Spätzle and Sauerbraten at the grocery store around the corner, or even the increasingly popular German-style Weihnachtsmärkte (Christmas markets), glimpses of my ancestry are almost always within reach. Approximately fifty million people in the United States are of German descent, and my native Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is well-known for its Pennsylvania Dutch language. The prevalence of our culture makes me confident that I will be able to pass many German traditions to the next generation.This album Japan: Ainu Songs, however, represents a people who do not share this luxury. Classified as 8b (Nearly Extinct) in Ethnologue: Languages of the World, the language and culture of the Ainu people are moving closer to extinction.1 When the Japanese took control of the Ainu people and their land in the 1860s, the Ainu civilization collapsed. Although forced to practice Japanese customs and integrate into mainstream society, they were segregated by the 1899 Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act, resulting in widespread discrimination that persists today.2 Presently, few members of the remaining 15,000 still speak the Ainu language, and traditional Ainu music only survives among the older population.3

AudioThe songs on this album fall into two general categories: religious ritual or secular songs. Most of the ritual songs (tracks 1-8, 10) surround the Bear Festival, the most important event in the Ainu religion, which concludes with the sacrifice of a young bear. The bear is viewed as the most powerful animal god, and this practice allows its spirit to return to its kingdom, while also sustaining a positive rapport between the people and the spirits.

One of the unique customs associated with this festival is cooking dumplings as an offering to the gods. This practice requires pounding flour (heard on track 3, “Iyuta-upopo”), accompanied by a work song sung by women. Dances play an important role in these rituals, as they allow people to emotionally connect with the gods. The words of this upopo (sitting song) are often sung as a round, and may be accompanied by beating a shintoko (the lid of a container) in addition to pounding the flour. Adding song and dance to the act of making dumplings was believed to “enhance delight and efficiency of work.”4

The culturally restrictive Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act was dissolved in 1997 and replaced by the Ainu Cultural Promotion Law, which finally granted the Ainu the right to practice their own cultural traditions.5 This law continues to provide the community with financial support to teach, promote, and research Ainu culture while also incorporating Ainu language and customs into national education and media. Although this law is a positive step toward moving the Ainu language and culture away from its 8b (Nearly Extinct) designation, there are still many hurdles to overcome in the areas of self-determination, land ownership, and discrimination.

Stephanie K. Andrews is a Sales & Marketing Intern at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, spending most of her time working with the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music. She holds a dual degree in Music Theory & Composition and Psychology, with plans to pursue a master’s degree to further research the intersection of ethnomusicology, psychology, and religion.

1 M. Paul Lewis, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2014. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Seventeenth edition. “Ainu: A Language of Japan.” Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com.2 Tessa Morris-Suzuki. 1999. “The Ainu: Beyond the Politics of Cultural Coexistence.” Winter 1999. Cultural Survival Quarterly (Winter).

3Lewis, Ethnologue, “Ainu.”

4“The Ainu People,” The Ainu Museum, accessed January 2, 2015, http://www.ainu-museum.or.jp/en/study/eng01.html.

5 Morris-Suzuki, Beyond Politics.

UNESCO Collection Week 41: Global Sounds of Love and Loss | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings