-

UNESCO Collection Week 42: Music from Java

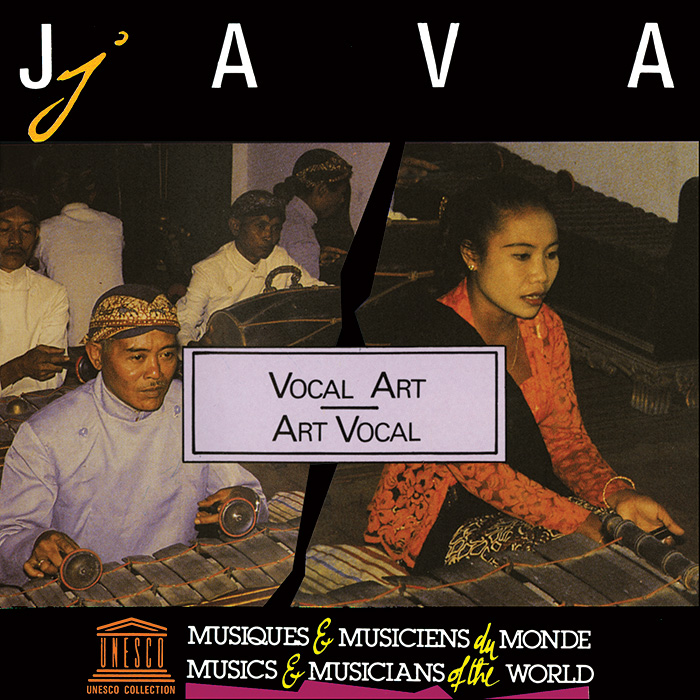

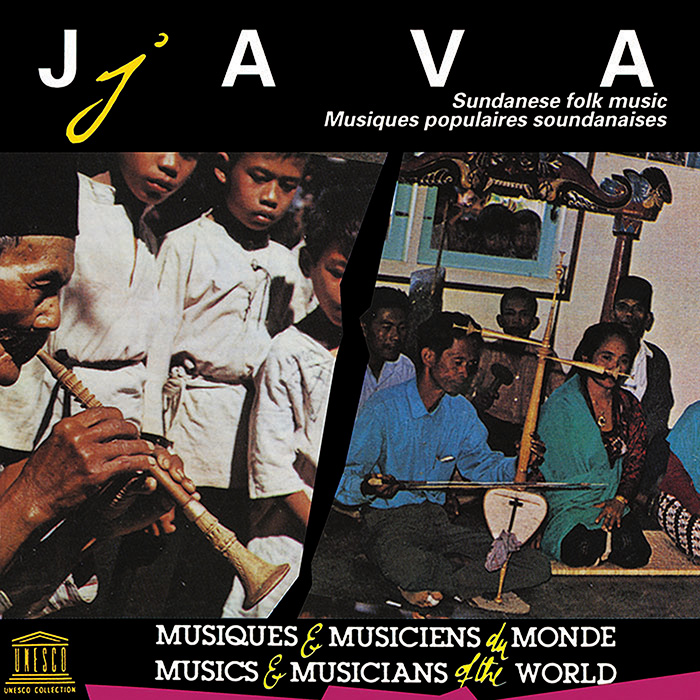

This week’s UNESCO releases, Java: Vocal Art and Java: Sundanese Folk Music, come from the Indonesian island of Java. Java is the most populous island in the world with an estimated population of 143 million people. These two albums provide an introduction to the two largest ethnic groups on the island: the Javanese (about 60%) and the Sundanese (about 20%). The island, however, is extremely diverse and is home to several ethnic groups, three major languages, and six official religions.

GUEST BLOG

by Stephanie Ho

Java: Vocal Art and Java: Sundanese Folk Music contain excerpts of contrasting and rich musical traditions that coexist on the same island. Vocal Art mainly looks at central Java, while Sundanese Folk Music concerns western Java and the dominant ethnic group native to this region. In the process of listening to these albums and reading the liner notes, I was reminded—as I have been reminded many times in my studies—of the great musical diversity that exists within the islands that make up Indonesia.

Java: Vocal Art, collected by Jacques Brunet, is an ambitious attempt at defining Javanese “vocal art.” From the vast repertoire that exists for so-called vocal arts, Brunet’s album focuses on one kind of musical poetry, the macapat. Upon reading Brunet’s notes it is understandable why the album showcases different renditions of macapat: “The macapat poetical system is found in all Javanese musical forms: concert music, dance, and theatre music.”1 It is also the predominant form of sung poetry in most musical performances that include a vocal part. The recordings in Java: Vocal Art represent three kinds of singing: court tradition (track 1), street ballad (track 2), and private performance (track 3).The tracks also build up in timbre: “The Legend of Dewaruci Kaca” (track 1) features a single male voice; “Gambirsawit” (track 2) combines vocals and a zither; “Siteran Gambirsawit” (track 3) includes female vocals, a reduced gamelan, and a male chorus. In this manner, the listener can first appreciate the role and talent of the soloist, then hear how the voice pairs with particular instruments, and finally listen to singers in the context of a bigger performance group. This gradual layering of voice and instrument also highlights the different aesthetics in which macapat is used as a focal point for vocal performance.

“The Legend of Dewaruci Kaca” is essentially a poem performed through song, featuring R. S. Banjasari, a former soloist of the Yogyakarta palace tradition. The soloist tells a story with his voice, oscillating between plaintive, nasal singing, and enunciating particular words slowly with a percussive emphasis to convey a somber tone. Listening to it, I am reminded of my experiences playing in wayangs (puppet theatre) and especially the ways the puppeteer, or dhalang, must singlehandedly narrate a scene that may feature multiple characters. In this case, obvious contrast in vocals is the only force behind creating different character archetypes.

Contrastingly in Java: Sundanese Folk Music, Brunet’s curating choices provide an overview of a diverse repertoire. Folk music is part of a cycle of musical production that ultimately creates no divisive line between so-called court/art music and folk/popular music: “popular music is essentially indigenous [….] Moreover, the music of the court was created by popular musicians using such refined melodic themes that, to the Sundanese, art music seems to be a part of the same heritage.”2 The six tracks in this album, which Brunet suggests are the most musically attractive, individually represent a different kind of ensemble. These different ensembles are distinguished by location, and Brunet’s liner notes often identify the respective village performance group.As a novice to the Sundanese musical traditions, one of my first tasks upon listening to the album was to determine the connection between the notion of “folk music” and what I actually heard in the individual tracks. What is folk? What is traditional? What is popular? I also noticed the presence and overlap of other Indonesian musical traditions, such as the angklung bamboo percussion ensemble (track 1), which is known to be popular in northern Bali.

I was especially struck by the second track, “Recak,” in which the tarompet oboe's nasal quality reminded me of similar sounding central Javanese vocal styles. The titular recak ensemble often accompanies burlesque dances and features the tarompet oboe accompanied by nine angklung, or bamboo idiophones.

AudioUnlike Java: Vocal Art, which develops upon one musical aspect—the use of macapat—Java: Sundanese Folk Music showcases various musical textures as differentiated by ensemble and featured instrument. However, both albums and their broad titles (“folk music,” “vocal art”) caused me to reflect upon the ways these broad categories are conceived. Using these two albums as immediate case studies, we see that two different regions in a relatively close geographical space create and uphold criteria for a musical tradition’s social importance. In Java: Vocal Art, the court style and pedagogy breeds virtuosity and local respect for a particular way of performing verbal art. In the second album, Java: Sundanese Folk Music, the social significance of Sundanese music is reflected through the region’s collective diversity in types of ensembles located in western Java. Both of these titles are value-laden, but as Brunet shows us in his two sets of liner notes, these values are determined locally and should be heard in such contexts.

Stephanie Ho is a second-year MA student at Wesleyan University (BA in Liberal Arts, Sarah Lawrence College ’13). She has previously written a series of articles (“An Introduction to...”) for a student newspaper based at the University of Oxford, UK. For her master’s thesis she is currently researching the Korean pop fandom located in Lima, Peru. Other research interests include Balinese gamelan, Balinese dance, and Javanese gamelan. She has previously been a member of the Oxford Gamelan Society, and currently performs with the Wesleyan Gamelan Ensemble as well as Gamelan Dharma Swara (NYC).

1 Jacques Brunet, liner notes to Java: Vocal Art, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1979, compact disc.

2 Jacques Brunet, liner notes to Java: Sundanese Folk Music, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1976, compact disc.

UNESCO Collection Week 42: Music from Java | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings