-

UNESCO Collection Week 44: New Discoveries in the Ancient Sounds of Uzbekistan

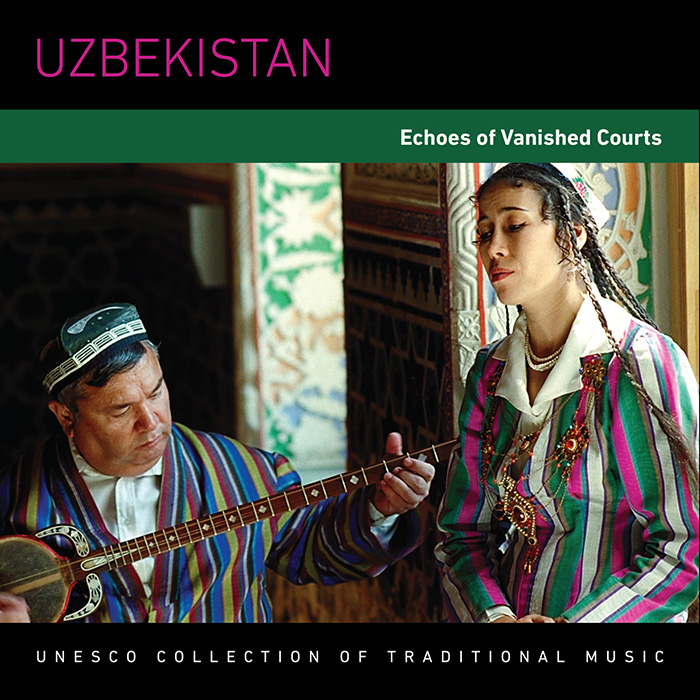

This week’s UNESCO releases, Uzbekistan: Music of Khorezm and Uzbekistan: Echoes of Vanished Courts, provide a comprehensive overview of the musical traditions found in Uzbekistan. Included in this post is an interview with Otanazar Matyakubov, co-compiler of Music of Khorezm. Paired with this album is the previously unreleased Uzbekistan: Echoes of Vanished Courts, which features 14th century palace music.

GUEST BLOG

by Joan Hua

Uzbekistan: Music of Khorezm, the once out-of-print recording, is now being reissued by Smithsonian Folkways. As a pioneering survey of Uzbekistan’s musical landscape, the album includes recordings of classical music, oral epics, women’s music, spiritual songs, and popular music. It is released in conjunction with a previously unreleased title Uzbekistan: Echoes of Vanished Courts, which documents the remnant of 14th century medieval palace music in Tashkent. The recordings reveal the enduring musical legacy in today’s context, wherein ensemble performance, as opposed to the traditionally prized solo improvisatory performance, predominates.

AudioOtanazar Matyakubov, referred to as OM, is the co-compiler for the 1994 recording Music of Khorezm. Between 1977 and 1992, he and Theodore Levin went on numerous expeditions in Central Asia to record the musical activities there. They compiled Bukhara: Musical Crossroads of Asia, which was released in 1991 by Smithsonian Folkways. In 1994, UNESCO commissioned and published Uzbekistan: Music of Khorezm. These recordings marked the first in-depth, scholarly inquiry on Uzbek classical music since the collapse of the Soviet Union.I met OM in fall 2014 at his daughter’s home in Arlington, Virginia. Over tea, dried fruit, and Uzbek pilaf, he told me stories about his expeditions with Theodore Levin.

I was the one who would ground Ted in the practical application of things. In return, he would drag me by my ears to the skies where the theory takes place.

OM said, during those fifteen years that they worked together, they covered every part of Uzbekistan—Khorezm, Bukhara, Surxandarya, Qashqadarya, and so forth.

One of the last expeditions we did as a team was to a place called Yagnâb. In Yagnâb, there was no electricity; there were no roads; there was no sign of modern life. Six months of the year you can’t even access it because it’s frozen. So we got there on donkeys. Ted is one of the most humane people I know. And he was so sorry for his donkey that he actually walked.

We arrived in Yagnâb and we tried to connect with people and ask them questions, but all we kept getting as an answer was, “I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know. . . .” And it’s true; people just didn’t know a lot about what was going on. One time we joined this family at their home. The older brother of this household was a mullah (scholar of Islamic theology and sacred law). So we would ask him questions, he would politely answer them, but our questions just did not engage him. I was acting as the interpreter [between Russian and a Persian language spoken by the Yagnâb people]. It was the last night of our visit. We thought we couldn’t find much and had planned to just head back the next day.

The mullah asked his younger brother, “Why don’t we slaughter one of our lambs to treat our guests?”

“What did he say?” Ted asked me.

I told him, “In your honor, our host would like to slaughter one of the lambs.”

“Please tell the mullah that instead of slaughtering the lamb, please kill me instead,” Ted said to me.

Suddenly the mullah became very alert and stood up like a bullet. He pointed at Ted and said, “There’s a true Muslim.” He started bowing to Ted. Suddenly he opened up and started having a conversation with us. His old instrument—an ancient Sogdian instrument, dombra [short, fretless long-necked lute]—appeared out of nowhere. It had two strings, it made probably four or five pitches maximum, and he started playing it!

Ted said, “We’re not going anywhere tomorrow; we have to record the mullah.”

AudioAt our interview, I wanted to know what changes have occurred and discoveries surfaced since the release of the UNESCO recording twenty years ago. OM preferred to start from the beginning—from the earth, as musicology was based on archaeological findings, to the heavens, where the “theory takes place” and musical analysis is grounded in philosophy, math, and science. Uzbek classical music has a turbulent history, and its resilience is remarkable. As Razia Sultanova writes in the notes for Echoes of Vanished Courts, traditional Uzbek music today can be heard on the radio and exists in the contexts of markets, shops, teahouses, baths, cafes, and tourist buses. They are traces of the medieval court culture that survived in spite of political disorder. Overcoming these crushing forces, and as radio and television transform ways of listening to classical music, the work of restoring what is lost is a long and involved journey.For decades, no one understood the Khorezmian tanbur notation, a maqam tablature primarily used in the 19th century to capture the melodies, rhythms, structural elements, and poetic texts of maqam that is untranslatable in Western staff notation. The Jadids who knew this notation system were all killed under Stalin’s oppressive regime in 1937 and 1938. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Music of Khorezm was the foremost scholarly look at Uzbek classical music.

Following the 1994 release, OM spent twelve years working to decipher the tanbur notation. And he has finally found the key. Recorded in sets of three rows, the notation is read from right to left as in Arabic script and corresponds to the eighteen frets on the tanbur (plucked long-necked lute) fingerboard. The syntaxes and rhythmic foundations (usul) for each piece of a maqamis spelled out in words. The codification serves to reestablish the melodies, rhythms, structural elements, and poetic texts that the musician already knows. “This absolutely unique way of recording music is the synthesis of theory and practice,” he said.When I spoke with him, he was finishing the last section of his book, written in Russian, wherein he will share his discoveries concerning thetanburnotation.

Understanding the notation system implies a reorientation of the study of Uzbek classical music. Today’s celebrated musicians were usually educated in music conservatories. The musicians learned to understand this enduring music through Western notation; they learned from their teachers the intricacies that are left out of the scores.

With the new light shed on the tanburtablature, it becomes possible to explore new depths of this musical heritage’s enrooted theories—developed by al-Farabi, by Avicenna—vis-à-vis contemporary practical applications. The music that was traditionally improvised could now be composed with this notation. The musical elements that were perceived to have belonged to oral tradition, transmitted only through personal contact, could now be disseminated through recorded music and in writing—on three rows, with sophisticatedly dictated rhythmic instructions.

An example of tanbur notation. Courtesy of Otanazar Matyakubov.

Uzbek classical music may owe its endurance to its strict aesthetic code, discouraging personal innovation and departure from the master’s way during the process of nazira, or imitation. Accurate notation of the music is also preservation; written music means anyone who understands it could learn the composition without a master to enforce the correct way. Applied to contemporary practice, written and recorded music becomes an avenue for creativity and even sustainability of Uzbek classical music.

OM began our conversation by stressing the importance of maintaining the truest form and liveliness of ancient court tradition in contemporary performances of Uzbek music. “But perhaps we are witnessing the last generation of this liveliness,” OM said acceptingly, “because urbanization is unstoppable.” There is hope that the audience and context for the venerable court tradition will find renewed meaning in modern life.

Joan Hua co-managed the production of the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music. She currently serves as guest editor for Smithsonian Folkways Magazine and content manager for Smithsonian Music.

UNESCO Collection Week 44: New Discoveries in the Ancient Sounds of Uzbekistan | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings