-

UNESCO Collection Week 49: Music of Herat

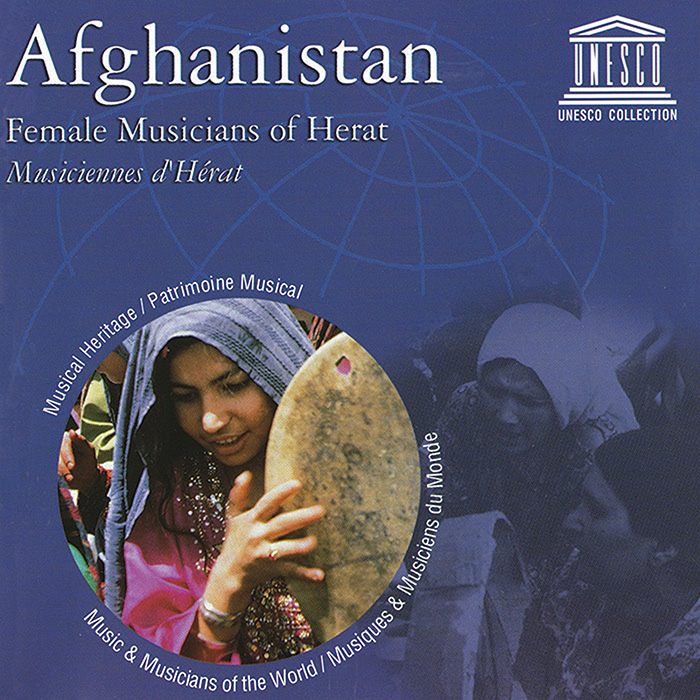

This week’s UNESCO reissues, Afghanistan: Female Musicians of Herat and Afghanistan: The Traditional Music of Herat focus on the traditional sounds of Afghanistan’s third largest city.

GUEST BLOG

by Jeanne Gillespie

Before the Internet, before radio, music moved freely along the trade routes that delivered exquisite luxury goods from the Far East to Mediterranean ports. Poetic and musical traditions were exchanged alongside musical instruments, spices, beauty products, and silk. The music collected by Veronica Doubleday and John Baily on the recordings Afghanistan: Female Musicians of Herat and Afghanistan: The Traditional Music of Herat exhibits the rich musical influences in one of the most important cities in the region of Khorasan, a kingdom that spanned parts of Iran, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan. As the liner notes to The Traditional Music of Herat explain, an Afghani proverb described Khorasan as the oyster shell of the world, with Herat as its pearl.When Alexander the Great arrived in Herat in 330 BCE, it was already a bustling oasis with rich grazing lands and trade routes stretching in all directions. He fortified the city with walls and a citadel that may still be seen today.

The famous Sufi master Abdullah al-Ansar (1006-1088 CE) hailed from Herat, and much Herati music still reflects the powerful influence of Sufi teachings. Numerous tracks from Traditional Music of Herat are Sufi works, and are still performed in the city. Sufi influence and tradition can be heard on tracks 2 (“N’at”), 3 (“Shajkh Ahmad-e Jam”), 9 (“Chaharbaiti”) and 10 (“Sufi Song”).

AudioFemale musicians also perform Sufi compositions. Track 5 [“Lullaby”] featured on Female Musicians of Herat, and track 11 [“Allah Hu”] on The Traditional Music of Herat use the invocation “Allah Hu,” which is a common phrase meaning “God is” from the devotional act of zekr (Dari: “rememberance”), a core Islamic meditative practice similar.

Despite dynastic rises and falls, massacres, invasions, and internal strife, Herat enjoyed a golden age in the early 15th century under the Turco-Mongol princess Gawhar Shad and her husband, Shah Ruhk, the son of Timur (Tamerlane). Afghan Persian (or Dari) language, literature, and culture flourished in Herat at this time, and Shad was instrumental in relocating the empire’s capital from Samarkand to Herat. As part of the relocation, she organized the construction of several of the most important architectural treasures still standing in the city, including the mosque that bears her name. Her mausoleum represents another spectacular architectural treasure of the city.Although Shad exercised power and influence in Islamic Herat during the early 15th century, by the time Doubleday and Baily visited in the 1970s the situation for women had changed substantially. Women and men operated in separate spheres and women were not active in public. In their research of Afghani music, Doubleday and Baily did, however, find a vibrant tradition of female musicians who played for female audiences at weddings and celebrations. As a woman, Doubleday had access to the Afghani ceremonies that Baily did not. Her work with female musicians offers details on a diverse range of performers of both Dari and Pashto heritage. A significant number of the songs collected by Doubleday were designed to entertain wedding guests and to comment on the activities of the celebration.

AudioThe song “Bada Bada” (track 4 from Traditional Music of Afghanistan) describes the preparations for the wedding, including painting henna on the hands and feet of the bride and the women of wedding party: “Tonight is the night for painting henna, my dears/ The bridegroom’s mother is laughing like an open pistachio nut, be blessed by God / Always be blessed/ Be rich and wealthy/ New bridegroom king, be blessed.”

AudioTrack 21 from Female Musicians of Herat, entitled “Leila, Leila, Leila,” reflects the multicultural aspects of this ancient city. In performing this composition a Pashtun woman named Adeh accompanied herself on her daireh, a large frame drum with bells, rings, or jingles heard on fourteen of the twenty-two songs on Female Musicians of Herat. This particular composition about a girl called Leila is written with a Dari verse that is interspersed with Pashto (Afghani) refrains. This is noteworthy, as most of the ethnic Pashtuns in Herat now speak Dari as their first language, although Pashto is common in rural areas.

In an article entitled “The Frame Drum in the Middle East,” Doubleday explains that the frame drum was popular in Arabian, Hebrew, and Assyrian cultures, but not as common in the Persian sphere(1999, 108-9). She comments in the liner notes that many female performers in Herat still use frame drums to accompany their compositions. In my research on women’s voices in the Hispanic world, I came across an image from the Golden Haggadah,a Hebrew manuscript from Barcelona ca. 1320 CE, that illustrates the prophetess Miriam playing a frame drum known in Hebrew as a tof that has been adorned with henna as the women make preparations for Passover.

Judith Cohen explains in “This Drum I Play: Women and Square Frame Drums in Portugal and Spain” that the square drum pictured in the haggadah was as common as the round frame drum in Iberia. Cohen also explains that in al-Andalus, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim women all played frame drums. Throughout the Iberian Peninsula, frame drums were decorated with henna patterns similar to those that the women used to adorn their bodies. The use of henna in the decoration of frame drums also seems to be a common practice in Herat. In a photo that accompanies the liner notes to Female Musicians of Herat, we see a young woman playing a frame drum with intricate henna details.

While Herat in the 1970s offered women limited opportunities for the creative and academic pursuits, the situation for women has improved somewhat in recent years. In 2003, a university named for Gawhar Shad opened in Kabul as a space in which Afghani women could pursue higher education.

The music and cultural heritage of the Afghani people can unlock cultural treasure and a better understanding of the Herati past, present, and future. Doubleday and Baily have videos of their work available on YouTube, and their work is regarded quite highly among the Afghani people.

Dr. Jeanne Gillespie is a faculty member in the College of Arts & Sciences at the University of Southern Mississippi and has taught courses at all levels of Spanish language and cultures, women’s and gender studies, and interdisciplinary studies.

Works cited:

Cohen, Judith. “ ’This Drum I Play’: Women and Square Frame Drums in Portugal and Spain.” Ethnomusicology Forum 17.1(June 2008) 95-124.

Doubleday, Veronica. “The Frame Drum in the Middle East: Women, Musical Instruments and Power.” Ethnomusicology 43.1 (Winter 1999), 101-134.

UNESCO Collection Week 49: Music of Herat | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings