-

UNESCO Collection Week 52: Traditional Music from Armenia and Yemen

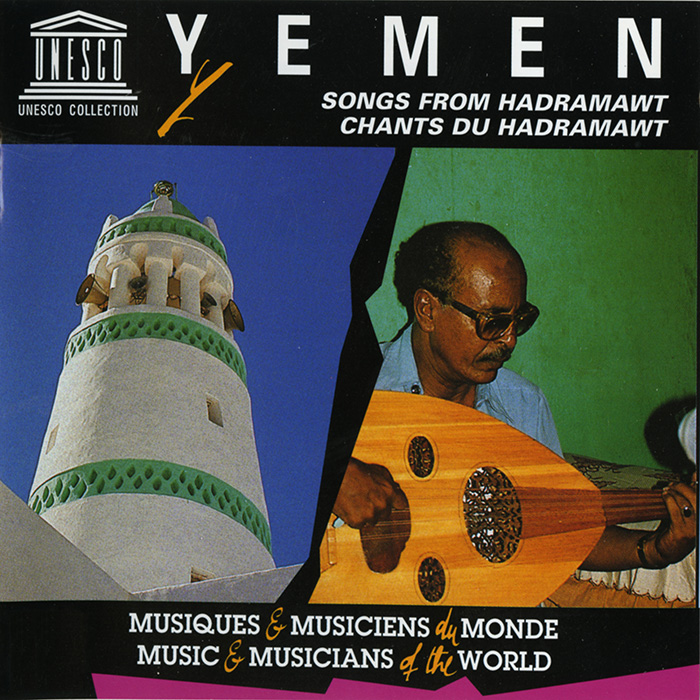

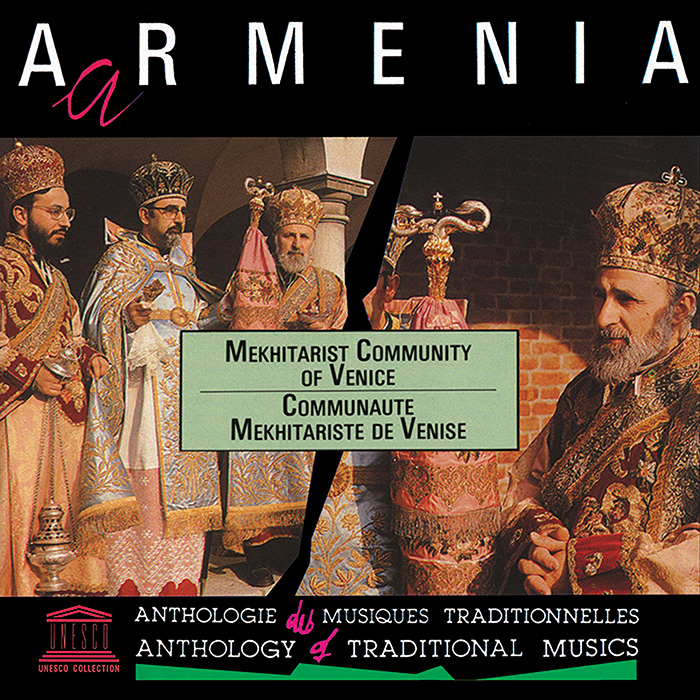

This week’s UNESCO reissues are Yemen: Songs from Hadramawt and Armenia: Mekhitarist Community of Venice. These albums feature traditional musical forms from each nation, as represented by various communities.

GUEST BLOG

Part One: Yemen: Songs from the Hadramawt

by Eugenia Siegel Conte

The Hadramout region spans the southeast portion of Yemen along the Gulf of Aden and reaches north into the Arabian Desert. This area encompasses an arid plateau and a network of wadis, seasonal waterways that have carved runs through the desert bedrock. Hadramout is known as a major producer of the aromatic resin frankincense.Traditional culture is valued and protected, especially a combination of music and poetry called dân. A diverse musical genre, dân is named from a word meaning “hummed melodies” – songs muttered. Used as a tool to vivify the lyrical poetry so prized in the region, iterations of dân are sung in a broad variety of contexts. The songs often use the word dân as a repetitive percussive refrain and are either accompanied (by the lute-like oud, percussion, or clapping) or unaccompanied, depending on the use, venue, and lyrical content.

Yemen: Songs from Hadramawt presents examples that demonstrate the use and versatility of dân throughout the region. The album is a sampler of several dân types, including pieces meant for entertainment and dance (tracks 2, 6, and 10), work songs (the dân of the camel drivers in tracks 3 and 7), and a showcase of improvised poetry (the excerpt from a dân session in track 5). A few traditional songs frequently performed in Hadramout outside of the dân genre are included (tracks 1, 4, 8, and 9), rounding out this compilation of field recordings.

A complex relationship between melody and lyric is stunningly apparent in track 2. Singing a contemporary, unaccompanied dân titled “Oh, Beautiful Nights,” (or “Diin tarab - Hayya layiili jamila”) Hussein Abdul Kadir al Kaf highlights the poetry with clear diction and focused vocal tone. The few moments of roughness, when he clears his throat before beginning a new verse, bring an incredible intimacy to this recording. It felt as if I was in the room listening to the artist’s dexterity and control, hearing the poem brought fully to life in music. Melismatic filigree in the melody enhances the text, allowing the words to rise like burning frankincense and diffuse in a poetic perfume of smoke.

Eugenia Siegel Conte is a Graduate Student in Ethnomusicology at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. She previously completed a Masters in Music Research at Truman State University in Missouri, and is currently pursuing research on Hawaiian and island musics, film music and world vocal musics. An avid choral singer, she performs professionally with the Hartford Chorale and Connecticut Choral Artists (CONCORA). Email: econte@wesleyan.edu

GUEST BLOG

Part Two: Armenia: Mekhitarist Community of Venice

by Stephanie Andrews

Օտար ջրերում հայացեալ Կղզի

Հայոց հին լույսն է քեզնով նորանում...

Հայրենիքից դուրս՝ հայրենեաց համար:An Armenian island in the foreign waters,

You rekindle the old light of Armenia...

Outside the homeland, for the sake of the homeland.In the middle of the Venetian Lagoon, the Armenian Catholic Monastery appears to be out of place. Why has the island of San Lazzaro for centuries been the hub for the Armenian diaspora, despite several countries and bodies of water between it and the homeland? The island is home to the Mekhitarist Order, founded by Abbot Mkhitar Sabastatsi in 1717.From first listen, it is apparent that a strong sense of tradition propels the choir. The Armenian tradition is far older than the monastery—it dates back to early days of Christianity. Although the Armenian rite was established in the 5th century, the Armenian church has roots in early missionary journeys by Thaddeus and Bartholomew, two of Jesus's twelve disciples, in AD 43 and AD 66.

This album features two different styles of Armenian chant. The first dates back to the 5th century (tracks 4, 6 - 12, and 14), now nearly impossible to understand by those outside of the tradition. This style only uses lyrics from Scripture and the original Armenian rite, with a complex notation of neumes.

The second style (tracks 1, 2, 3, 5, and 13) features songs from St. Nerses Shnorhail (1102 - 1173), the Patriarch of the Armenians. These songs come from a collection of several thousand called the Sharakan (“row of jewels”), which was created to capture the community’s emotional response to their beliefs. As a result, the text is a mix of scripture and unique writings. This style is characterized by a soloist who performs a steghi, or melismatic chant, above the rest of the choir’s ison (drone).

Before the island was given to the monks by the Republic of Venice, it was largely used as a place to banish lepers (it is named for St. Lazarus, the patron saint of lepers). By the mid-16th century it was virtually abandoned. Today, however, the monastery is known for its vast collection of Armenian books, artifacts, and manuscripts. The island continues to be a beacon for Armenian culture, building on the hopes of founder Abbot Mkhitar Sabastatsi.

Stephanie K. Andrews is a former sales and marketing intern at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. She holds a dual degree in music theory and composition and psychology, with plans to pursue a master’s degree to further research the intersection of ethnomusicology, psychology, and religion.

UNESCO Collection Week 52: Traditional Music from Armenia and Yemen | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings