-

UNESCO Collection Week 54: The Hidden Similarities of Madagascar and Malawi

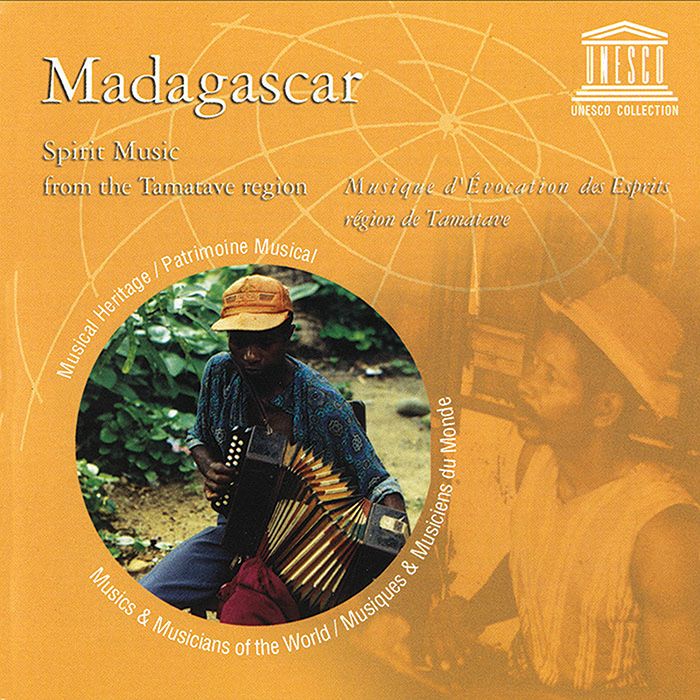

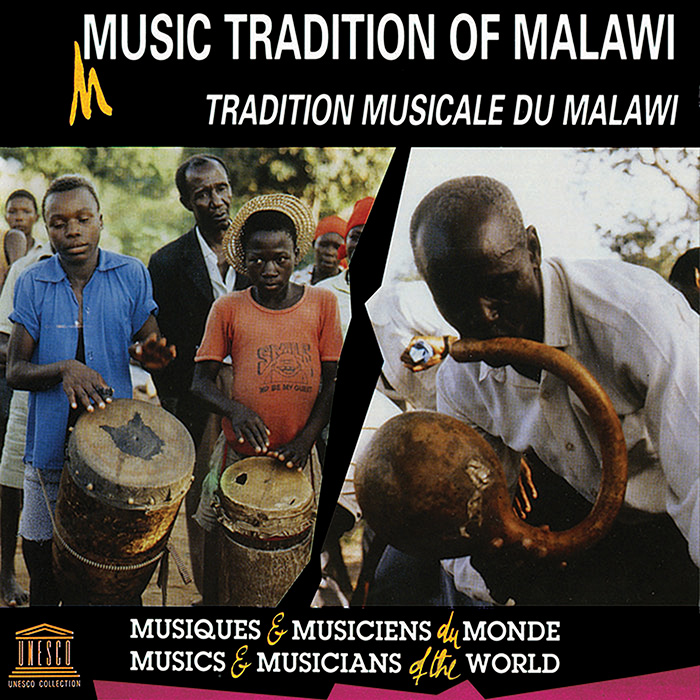

This week, explore how the two seemingly different nations of Malawi and Madagascar have more in common than meets the eye, evident especially in their musical traditions in the UNESCO albums Madagascar: Spirit Music from the Tamatave Region and Music Traditions of Malawi.

GUEST BLOG

by Logan K. Young

Nine hundred seventeen miles and almost two flight hours away from Lilongwe, the capital of the Republic of Malawi, lies the Indian Ocean port city of Toamasina, Madagascar—a cosmopolitan capital in the nation’s Atsinanana region. Locals refer to the city as Tamatave.

Malawi, meanwhile, was conquered by Britons. Landlocked in rural sub-Sahara by Zambia to the northwest, Tanzania to the northeast, and Mozambique on the east, south, and west, Malawian culture, be it literary, musical, or plastic, is hardly the bouillabaisse that the French found stewing across the Mozambique Channel. Of course, there’s also the question of size: specifically, pure land mass.

Madagascar is a sprawling 226,597 square-mile country, previously the Malagasy Republic. And that little sliver of good earth called Malawi, first known as Nyasaland, is only a mere 45,747 miles squared, nearly five times smaller.

So, if these countries are seemingly so different, why seek any similarity at all?

Starting with topography, the two countries are large-scale plateaus. So, on surface alone, there is a natural congruity.

Madagascar’s own national anthem starts “Ry Tanindrazanay malala o” (“Oh, Beloved Land of Ancestors”). Velontsoa Dodoka, the artist on this piece, accompanying himself on the mara tady (a pine box strung through with two courses of unraveled industrial cable, supported by moveable bridges), presents a song of divination, complete with all the improvisational flourishes he and his tribe favor. It remains one of the most telling examples of Antandroy sikidy on Madagascar: Spirit Music from the Tamatave RegionAudioBy turning our gaze even further into history, more similarities between Malawi and Madagascar can be seen.

Both were originally settled by migrant Bantu populations. Simply knowing there was shared ancestry lends further poetic credence to exploring these nations together.

Case in point, as Atta Annan Mensah writes in his essay “Music South of the Sahara” from Musics of Many Cultures (ed. Elizabeth May): “Awareness of old cultural links and the growth of new ones among the various countries of the African continent make regional divisions seem less and less meaningful.”

Here, on Music Traditions of Malawi (UNES08265), once more, it’s the music for movement, albeit with three graduated drums, that says the most about that country’s past lives in the bush of ghosts (referring to Eno and Byrne’s 1981 album My Life in the Bush of Ghosts and emphasizing the ancestral nature of the literal “bush” of the Malawian savannah.”).AudioThe tchopa is a circular dance of supplication, intended to invoke rains on the southernmost tip of the Great Rift Valley. Rendered by the Alomwe people in their Elomwe tongue on the Januwale outskirts of Thyolo, this performance is slightly more secular, taking a mortal man’s name, Saulo, for an official subtitle.

Compared to Velontsoa Dodoka’s dexterous whimsy from Malawi, heard above, this highly choreographed rite of spring might not sound quite as free; however, it’s no less reverent, every bit as spiritual, and, ultimately, highlights the most salient musical trope shared between these two otherwise wholly different nations: utility.

To be sure, the UNESCO compiler Ron Emoff discovered a wealth of music in Madagascar: Spirit Music from the Tamatave Region, as did the many folks who labored en masse to compile all of the sounds for Music Traditions of Malawi.

And heard here on these two exquisitely re-mastered discs—be it in the tromba from Toamasina or on the bodies gathered round the savannah—is a uniting force of purpose, the same kind of province that Alan P. Merriam wrote about in his 1957 liner notes for Folkways’ Africa South of the Sahara (FE 4503).

“The stress,” as Merriam put it, “placed upon musical activity as an integral and functioning part of the society.”

In Malawi, as in Madagascar, the making of music is a communal endeavor, rich in the mutual resource of ritual.

In Occidental measures, not that such a dichotomy is ever fair, Dodoka and “Saulo” are as utilitarian as Bach’s Goldberg Variations, as matter-of-fact as Brian Eno. No sound for sound alone, from the sikidy of the Antandroys to the Alomwe’s tchopa, rarely is there music-making for music’s own sake.LOGAN K. YOUNG is the editor-in-chief at Classicalite. The author of books on Mauricio Kagel and La Monte Young, he’s been published everywhere from NPR to the International Association for the Study of Popular Music to the liner notes for pianist Valentina Lisitsa’s new album of Chopin and Schumann études (Decca). He lives in Virginia, scant miles away from the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archive and Collection.

UNESCO Collection Week 54: The Hidden Similarities of Madagascar and Malawi | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings