-

UNESCO Collection Week 56: Classical and Folk Traditions in Indian Music

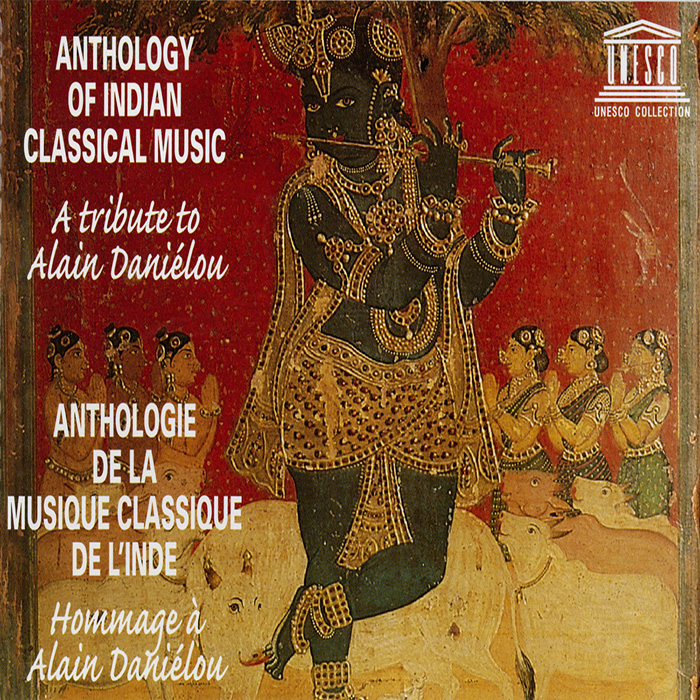

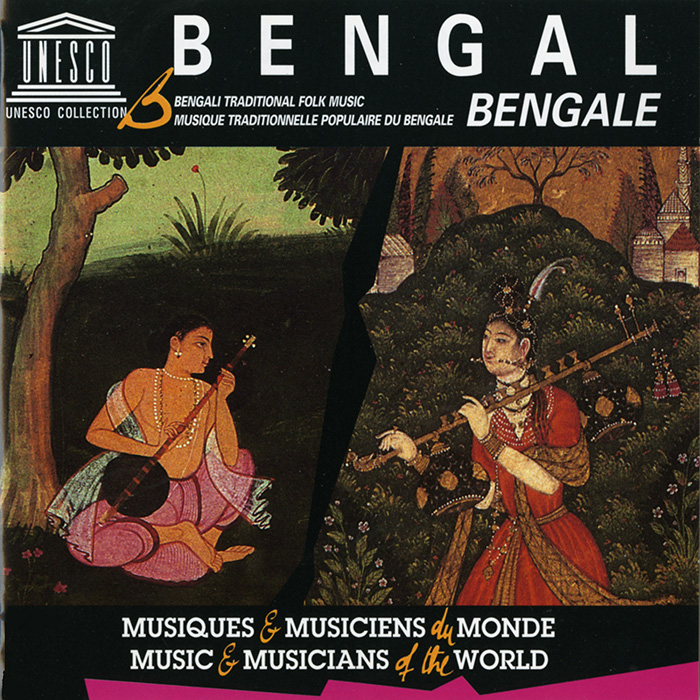

This week’s UNESCO reissues—The Anthology of Indian Classical Music: A Tribute to Alain Daniélou and Bengali Traditional Folk Music—explore India’s rich musical traditions, both in classical and folk forms.

GUEST BLOG

by Sita Reddy

By any measure, this week’s releases from the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music are historical firsts. Paired because they feature pioneering collections of traditional Indian music recorded in the 1950s—classical in one case, folk in the other—they also nicely complement each other on that vexed question faced by ethnomusicologists from the Indian subcontinent: are classical and folk forms of traditional music two sides of the same coin?

Scholars from India and Pakistan have long suggested that far from a rigid dichotomy, there is in fact a long and porous continuum between classical and folk traditions. Without getting into the chicken-egg dilemma of prior origin, there is no denying the deep symbiosis of these musical forms in the South Asian context. Classical Hindustani and Carnatic ragas (modes) often refine folk tunes in their melodic signatures (pakads), giving them formal rigor and structure, whereas folk music offers an expansive popular voice and cultural memory bank to the intricate ragas of classical compositions. This complementarity, this musical give and take, is beautifully expressed by the two albums mentioned below, albeit in very different ways. The Anthology of Indian Classical Music: A Tribute to Alain Daniélou suggests the universalism of “Music” (in Daniélou’s formulation, he rarely spoke of non-Western or Eastern music, just Music), whatever the subgenre or ethnic origin. The other—Bengali Traditional Folk Music—points to the particularity of place or language in folk music, to the local identity of the itinerant Baul singer-bards who travel from village to village, or the boat communities who sing bhatiyalis inspired by Bengal’s rivers, marshes, and rural hinterland. If the first reminds us that “Music” is “Music,” as Daniélou put it, whether it is classical or folk, the second reminds us that East may always be East, even when the musical twain does meet.

A word first on their unique production histories and what seems, at least on the surface, to be their differences as collections. The Anthology of Indian Classical Music is an extraordinary starting point, given that Alain Daniélou (1907–1994) himself was the prime mover of the UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music. In light of Daniélou’s seminal influence on Indian music, it is relevant to note that this was the “first of this (Indian classical) music to become available in the West in which the recorded pieces were not presented as ’folklore’ but as ‘serious’ music.” First released as LPs in 1955 by Ducretet-Thomson (EMI), the anthology was digitally re-mastered in 1997 and issued by AUVIDIS/UNESCO as a 3-CD set in homage to Daniélou. The set includes the very first recordings published in the Western world of a young Ravi Shankar (CD 1; Track 3) and Ali Akbar Khan (CD 1; Track 10), artists who both became worldwide legends in the Indian classical music pantheon, responsible for introducing an entire generation, both diasporic and subcontinental, to Hindustani music of the khayal form.Audio“Sitar, Sarode et Tabla”, a duet between the two maestros, disciples of the same teacher Ustad Allauddin Khan, offers some indication of their musical genius even early on. But those are not the only gems in this anthology. Also featured are early recordings of such luminaries as Mohinuddin and Aminuddin Dagar (the Dagar brothers from the dhrupad tradition) and D.K. Pattamal, T. Viswanathan, T. Ranganathan, and Balasaraswati and troupe from the Carnatic or South Indian classical tradition.

AudioAudioAnd indeed, some of these tracks are standouts. D.K. Pattamal’s beautifully rendered “Varali Mode” is particularly noteworthy, as is Balasaraswati’s “Jatisvaram”. And it is not ultimately surprising that Rolling Stones front man Mick Jagger selected Tyagaraja’s gentle composition “Sandehamunu,” performed by T. Visvanathan and T. Ranganathan, for his “Top of the World” CD and playlist.

AudioThe album Bengali Traditional Folk Music, on the other hand, tracks a different recording history, and thus a different emotional valence. Recorded by Daniélou along with Manfred Junius and Samir Naguib (and re-mastered in 1998 by AUVIDIS/UNESCO), the CD consists of a somewhat eclectic combination of folk melodies sung by Bengal’s Baul singers and boat communities, as well as devotional songs and hymns with predominantly Hindu religious themes, such as semi-classical bhajans and kirtans. As the brief liner notes describe, Bengal’s folk singers use flutes, drums (khol), cymbals, and various kinds of string instruments (ektara or dotara) for accompaniment. And the first three tracks of Baul songs in the album offer haunting renditions of how these songs can evoke so much pathos with so little adornment.AudioThe bhatiyali that follows is equally moving and equally spare. This is a love song to Krishna (Shyama, or the Blue-Skinned One), the eighth incarnation of Vishnu, but it transports the listener to the rivers and marshes that crisscross Bengal and the boat communities that sing their songs. Two flute tunes follow, played by Deboo Bhattacharji and Ahmed Shafui, each accompanied by tanpura (drone) or dotara and drums (dholak or khol). And finally, the bhajans and kirtans, which are more elaborately arranged devotional songs and hymns performed by various artists, first by Rathin Ghosh and party (Tracks 8 and 9), and later in the album Firdausi Begum (Track 10) and Sham Sunhar Karimar (Track 11).

The bhajan at Track 8 is particularly interesting for its historical resonance. Derived from Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda, a 10th-century lyrical verse-poem on the love between Krishna and Radha, it describes the Dasavatars(ten avatars) of Vishnu, the protector of the Universe in the Hindu religious pantheon. And in this particular performance, the primary singers (accompanied by cymbals, dholaks, harmonium) powerfully convey some of the transformative musical fervor, the bhakti (devotion) that must have characterized 18th-century Bengal’s new religious movements such as the Vaishnava Bhakti traditions as they burst upon the scene and forever changed not just religious but nearly all musical practices in North India.

AudioIf Alain Daniélou were to have the last word (as he should), he might say that “Music” may be “Music” anywhere, but if recorded and documented with soul and context, it becomes an extraordinary lens into history somewhere.

Sita Reddy is a Research Associate and former Fellow at CFCH. She is a scholar-writer, curator, and activist who now divides her time between DC and Hyderabad, India. Currently a Baird Fellow at the Smithsonian Libraries, she is continuing her work on yoga, and embarking on new projects on botanical art archives and Hyderabad museums. Among the great joys of her new nomadic life is being able to listen to live jazz in DC and live qawali in Hyderabad on a regular basis. sitared@gmail.com

UNESCO Collection Week 56: Classical and Folk Traditions in Indian Music | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings