-

UNESCO Collection Week 62: Modal Music of Azerbaijan and Badakhshan

Ethnomusicologists Sarah Hankins and Jonathan Withers explain how unique qualities emerge from hybrid musical cultures in this week’s UNESCO releases, Azerbaijan: Azerbaijani Mugam and Tajik Music of Badakhshân.

GUEST BLOG

by Sarah Hankins and Jonathan Withers

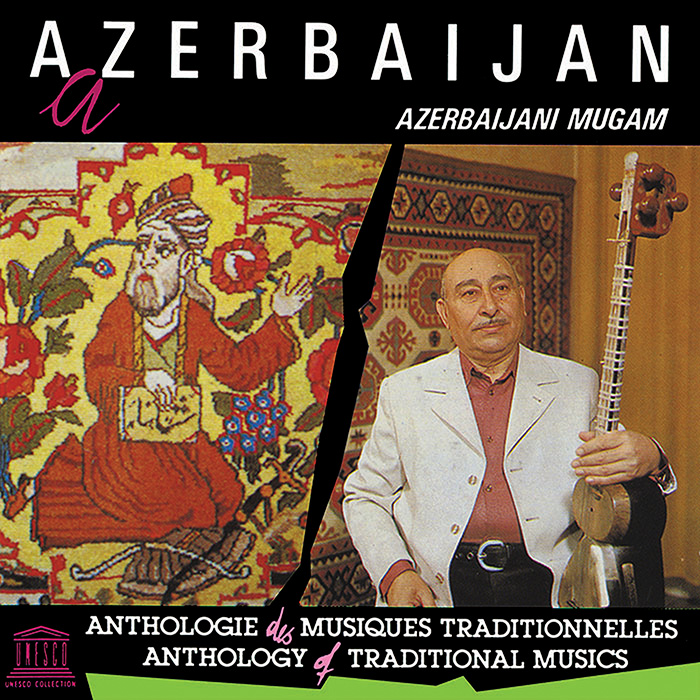

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijani mugam, a system of modes and their vocal and instrumental development, shares a theoretical lineage with the Persian dastgah system, and is also related to Arabic and Indian classical musics, which have similar modes and structures of elaboration. Like its Persian, Hindustani, or Arab-world kin, Azeri mugamis familiar to many audiences in the ensemble form, where a singer is accompanied by lute, bowed strings, and drums, or even by a symphonic orchestra. This 1978 UNSECO recording of virtuoso Bahram Mansurov (1911-1985) on solo tar is therefore a valuable cultural document, revealing the nuance, complexity, and intellectual refinement that lies at the heart of traditional mugam.In the hands of Mansurov, the eleven-stringed tar is by turns subtle and sweeping, hushed and stentorian. Different plucking and strumming patterns produce an array of tones and dynamics, and cover the range of rhythmic variations essential to the mugam system. Mansurov’s unaccompanied playing offers listeners subtle evocations of a much larger ensemble. His introductory free improvisations (bardasht) put us in mind of a singer’s melismatic vocal flights, while his powerful statements of characteristic mugam themes approach the grand, march-like spirit that massed instruments convey when playing in unison.

The recording is remarkable for the range of musical expressiveness that Mansurov displays. A comparison between any two tracks reveals technical and expressive differences that allow Mansurov’s solo tar to realize the “spirit of mugham,” the appreciation of which separates mugammasters from other musicians (During 2000, 534). In “Mugam Mahur-Hindi,”Mansurov uses a number of techniques that give the performance a playful effusiveness characteristic of that mugam. As in the other performances on this record, the piece begins in elastic meter, which then gives way to segments with more rigid rhythmic organization. These melodies are repeated and varied, mainly rhythmically, while only rarely diverging from a heptatonic collection of pitches. In “Mahur-Hindi,” Mansurov enriches many of the more strictly metered segments by strumming across multiple strings and string-crossing. The segment beginning at 11:00, the climax of the performance, is a particular highlight.

AudioContrasting with the playfulness of “Mahur-Hindi,” “Mugam Shur” is more gradual, perhaps more contemplative. Mansurov creates this atmosphere through a slow, relaxed introduction to the characteristic pitches and phrases. The repetition of short phrases that gradually build in intensity as they incorporate variations of pitch and rhythm introduce the listener to the character of shur, as exemplified at 0:33. As in “Mahur-Hindi,” “Shur” links lyrical phrases with cadential patterns that drive the performance forward with insistent rhythms, well befitting mugam’s aesthetic goal of ascension. However, this insistence comes from alternations between notes (a recurring pattern found throughout the recording) rather than from the exuberant sweeps across the strings in “Mahur-Hindi.”

AudioThe contrast between these two pieces is but one example of the breadth of Mansurov’s technique. This seven-piece recording provides a view of the scope of Mansurov’s mastery of his instrument, a mastery required for his unaccompanied tar to captivate listeners as much as mugamensembles consisting of tar, kəәməәnçe, and dəәf.

Badakhshan

Like Azerbaijan, the region of Badakhshan (spanning parts of modern-day Tajikistan and Afghanistan) was once part of the Soviet Union, and its traditional musics benefitted from preservation attention by Soviet musicologists. Tajiki Badakhshan also shares with Azerbaijan a hybrid musical heritage, blending Persian, Arab-world, and South Asian influences. Yet it is an impression of Tajik cultural uniqueness, rather than cross-regional or historical affinity, that emerges most strongly from this recording. Listeners may discern the craggy Pamir mountainside in an asymmetrical rhythm played on the dayre frame drum, or hear the wind sweeping across the plains as a spike fiddle gives out its long, slow wail.Although Tajik music has a codified theoretical system in the shashmaqom (six maqām) of historic Bukhara, this recording features mostly non-professional musicians performing “folk” pieces, such as lullabies, wedding dances, and songs to sing while herding or farming. Other pieces, religious in nature, praising Imam ‘Ali, draw from devotional Persian poetry, while still others are lengthy instrumental suites with all the stateliness of concert music. The recording seems to move freely between folk and classical forms, religious and secular themes, in a kind of call-and-response that reflects the bracing responsorial singing style typical of Tajiki vocal music, as in the album’s opening “Suite of songs.”

Many of these pieces are repetitive: instruments and voices re-state one or two brief themes over and over, with minimal variation. This melodic and harmonic simplicity, which facilitates either nostalgic contemplation or dancing, depending on the context, is often set against polyrhythms, odd meters, and rhythmic changes in mid-song. “Wedding air and dance,” for example, sits on such a challenging pair of rhythms that it is difficult for an outside listener to imagine how dancing would take place.

AudioMeanwhile, “Falak song on the setayesh rhythm” arguably scans in 3/4 or 6/8 time, yet the emphasis that drum and lutes place on particular beats gives a complex and undeniably non-Western rhythmic feel.

Given the distinctly Tajiki soundscape of this recording, which is produced by rhythms, harmonies, tones and timbres alike, listeners may find “Falak-i talqin” to be a most surprising offering.

AudioThis sweetly melodic piece on solo setar lute, which is marked by light fingered ornamentation and warm tones in the lower register, would be right at home alongside Western guitar-based folk or singer-songwriter music. In its gently familiar notes, “Falak-I talquin” paradoxically offers listeners strong evidence of Tajik musical singularity: as one of the only Eastern traditions that makes use of the chromatic scale, this music can sound, at times, almost nothing like its neighbors.

References

During, Jean. "Two Essays on Recordings of Music from Azerbaijan (Review)."

Ethnomusicology 44.3 (2000): 529-538.Sarah Hankins received her doctorate in ethnomusicology from Harvard University, and is currently a Lecturer at Northeastern University. Jonathan Withers is a Ph.D. candidate in ethnomusicology at Harvard University, completing a dissertation on Kurdish music in Turkey.

UNESCO Collection Week 62: Modal Music of Azerbaijan and Badakhshan | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings