-

UNESCO Collection Week 63: Instrumental Music of Northern India

Music student Hannah Judd discusses raga and the Hindustani music tradition with this week’s UNESCO releases, North India: Instrumental Music - Sitar, Flute, Sarangiand North India: Instrumental Music - Rudra Veena, Vichitra Veena, Sarod, Shahnai.

GUEST BLOG

by Hannah Judd

At the heart of Hindustani (North Indian) classical music is the raga, an elusive but essential concept derived from the Sanskrit word for “color” or “love.” A raga is difficult to define but can be understood in terms of what it is not: in the words of Harold S. Powers, "A raga is not a tune, nor is it a 'modal' scale, but rather a continuum with scale and tune as its extremes." Ragas give structure to improvisation by imposing limits: an ascending and descending scale, a specific mood or feeling to be conveyed to the listener, note order, the time and season during which the raga is played, melodic motifs, and embellishments and phrases that are either universal for the raga or unique to a particular school of musicians.

Within those guidelines and the structure of Hindustani music, musicians are free to make their own stylistic choices: the same raga played by three different musicians, while recognizable in each case, will be rife with variation that reflects the open-ended nature of the form, while different ragas will all retain their own distinguishing characteristics. This week’s two UNESCO albums, both of North Indian instrumental music, demonstrate the diversity of instruments and styles in their presentation of seven ragas.

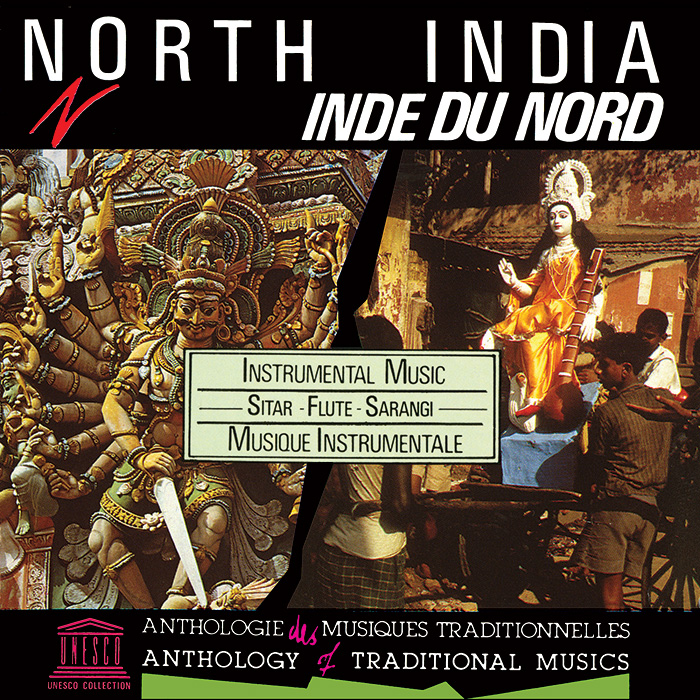

North India: Instrumental Music - Sitar, Flute, Sarangi

Noteworthy in traditional North Indian music are the focus on oral tradition and the one-on-one relationship between a teacher and a student. Because of the documented lineage of teachers (sometimes literally— musical instruction can stay in families) in different gharanas (traditions or schools of playing), there are traits that stand out in individual players as hallmarks of a gharana. The guru-shishya (teacher-student) relationship is intense and solitary: the student works only with the guru for years. The meditative single-mindedness of pursuing Indian classical music is admirable; it becomes apparent when listening to these recordings that the musicians involved have not only great technical skill but also a deep concentration and ability to listen born from years of dedication to their music.This album showcases three different ragas played by three different melodic instruments (all accompanied by tabla and tanpura): the sitar, flute, and sarangi. The sitar is a plucked gourd instrument, the flute is an open bamboo wood instrument, and the sarangi is a square bowed instrument used to accompany a vocalist or as a solo instrument.

AudioThis is an evening raga, one that originates from the folk melody “Rajasthan.” The name Desh means “of the country.” Because of this, Desh has been used as the basis for many patriotic compositions, including “Vande Mataram,” the national song of India. The raga’s performance here evokes the late evening, and the traditional instrumentation showcases the folk melody to its best advantage.

The sitar player on this raga, Ustad Ghulam Hussain Khan, is from the gharana of the Maharaja of Indore. His guru and brother, Ustsad Usman Khan, was a famed veena player. Studying under a veena player gave him a sound derivative of veena style and technique, which adds an interesting color to his sitar on this recording. The sitar is accompanied by Usta Nizamuddin Khan on the tabla and Pratima Parekh on the tanpura (the instrument that provides the background drone).

AudioThis is a combination of ragas Bihag and Kalyan (also called Kalyani or Yaman). It is a romantic raga, meant to be played at midnight. The sarangi player, Nazir Ahmad, plays the raga in the khyal style, an ornate style usually used by vocalists, considered freer with expression and improvisation than the traditional dhrupad style. The bowed quality of the sarangi, as well as the khyal style embellishments, make this sound similar to a vocal performance: expressive and passionate.

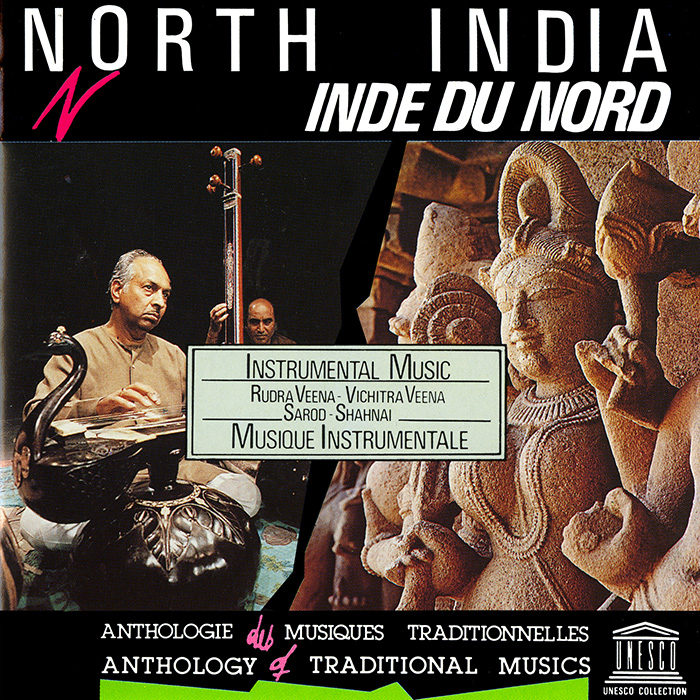

North India: Instrumental Music - Rudra Veena, Vichitra Veena, Sarod, Shahnai

This album is similarly structured, but it showcases four different ragas: three complete and one presented only in introduction, or alap. The album features a different melodic instrument for each track: the rudra veena and vichitra veena (two gourd instruments, played while sitting), the sarod (a lute-like plucked instrument) and the shahnai, an instrument similar to an oboe. The four ragas in this album are accompanied with excerpts of Sanskrit poems in the liner notes, which help listeners to fully understand the sentiment of each raga by presenting an idea or story for the mind’s eye to match to the music.AudioThis track is the only one on either album which presents a separated part of a raga rather than a whole piece. The alap is the meditative, unmetered introduction to a raga, played as an improvisatory prologue to the gat, the portion of the raga where the drums enter and a fixed melody is played rhythmically. This alap, for Raga Gunakali, uses the vistar, meaning the notes of the raga are introduced one at a time order of ascension. Gradually, after all the notes of the raga have been introduced, the tempo speeds up and the veena player more frequently strikes the drone strings to introduce rhythm towards the eventual inclusion of drums and the beginning of the gat, but because this is only a recording of the alap, we never reach the culminating rhythmic peak and the piece is left incomplete. A separation of parts is atypical and would not happen in a performance, but it provides an interesting chance to examine the alap apart from the rest of the piece: the listener is left in a meditative place, waiting and ready to move forward.

Raga Gunakali is an early morning raga, meant to be calm and melancholy. The liner notes provide this short excerpt from a Sanskrit poem, meant to communicate the feeling and atmosphere of the raga:

“Faithful, dear to cowherds, adorned with a golden pigment, mysterious in her movements, Gunakali is said to know of hidden treasures.”

Raga Bageshavri is a calm night raga. Played in this performance by Ashok Roy on sarod, it is meditative and beautiful. It is in teental, meaning there are sixteen-beat phrases. The sarod gives it a gentler tone: it doesn’t have the lower octave of the veena or the brighter quality the sitar gains from many sympathetic strings, and as a result, the sound is mellow and rounded, perfect for an introspective raga such as Bageshavi. The Sanskrit poem that accompanies the raga in the liner notes is one that speaks of romance and mentions the lute, reinforcing the choice of sarod for the melody:

"Her voice seductive when she is near her lover, Bageshvari is lovely, desirable. With eyes large like the lotus and a flawless pale body, she plays upon the lute her songs of love.”

Hannah Judd is a Smithsonian Folkways intern and a rising junior at the University of Pennsylvania, where she majors in music. Classically trained as a cellist, she has also studied sitar under Dr. Allyn Miner.

UNESCO Collection Week 63: Instrumental Music of Northern India | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings