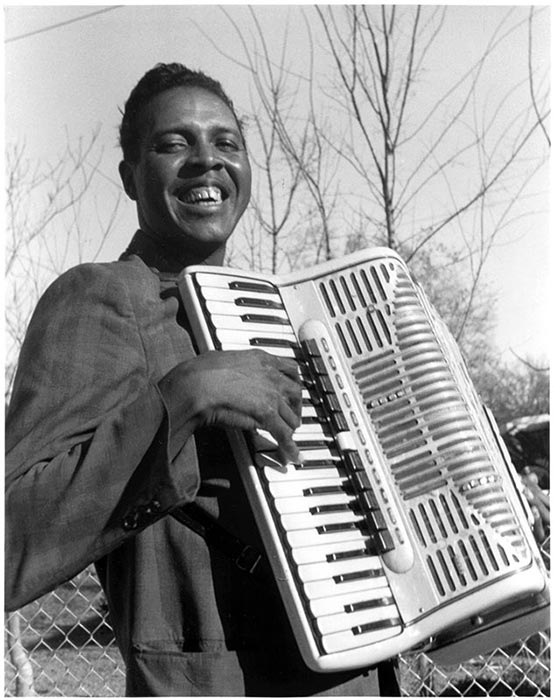

Clifton Chenier

Clifton Chenier, one of the true innovators of Louisiana music and zydeco’s great ambassador to the world stage, was born on June 25, 1925, in the countryside near Opelousas. “I come from out a hole, man,” he once joked, “I mean out the mud, they had to dig me out the mud to bring me into town.” Chenier learned to play zydeco by watching and listening to performances by family friends. In an interview with Ben Sandmel, published in Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People, Volume 1 by Ann Allen Savoy, Clifton recalled: “They had an old Model A Ford with a rumble seat in the back, so when they’d pass by my daddy’s house to go play a dance I’d jump in that back seat, and when they’d get where they’d gone to play I’d get out the car. They couldn’t do nothing, it was too far for me to walk back. I’d stay with ’em and listen to ’em. I was about eight or nine.” At an early age Chenier had already found his calling: “I always kept it in mind that, if I ever was going to be a man, I was going to play accordion. But what’s more than that, I was going to play it one way: my style.”

Although rooted in Creole folk tradition, Chenier was a forward-thinking modernist who stayed well aware of current trends. He learned the R&B and blues hits of the early 1950s by Fats Domino, Big Joe Turner, Louis Jordan, and B.B. King — and, later, Ray Charles, Slim Harpo, Jimmy Reed, and even Wilson Pickett. Chenier proceeded to “zydecorize” his favorite songs by these artists, playing them on the accordion and singing quite a few of them in French. Zydeco has always been a hybrid genre, and Chenier’s repertoire also encompassed Cajun waltzes, the Creole pre-zydeco sound known as la-la, deep folkloric blues, country hits, R&B, big-band standards, South Louisiana swamp-pop, music of the Native peoples of the region, and more — even recording a song entitled “Zydeco Disco” during the 1980s.

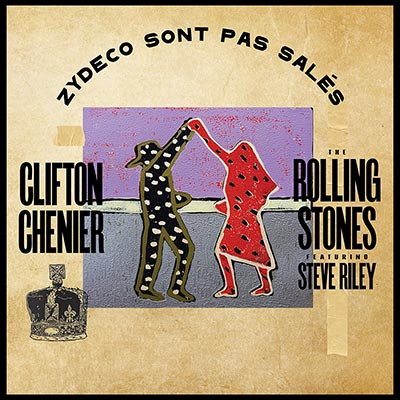

Zydeco is an exuberant style of dance music that originated within the Black French-speaking communities of Southwest Louisiana. (The term “Creole” also refers to these populations in Louisiana, with varying definitions.) The word “zydeco” is said to come from the French word haricots, which translates as “beans” in English and more specifically, in Louisiana, as “snap beans.” The French expression “les haricots sont pas salés” literally translates as “the snap beans are not salty,” and figuratively as a metaphor for times so hard that people can’t afford salt to season their food. The word evolved into the name and the spelling for this rollicking accordion-based music, as heard on the anthemic “Zydeco Sont Pas Salés.” In 1934 the Library of Congress folklorists John and Alan Lomax made a field recording of a song including this line, marking the first time it was ever documented.

Clifton Chenier’s mission statement was simple and direct: “If you can’t dance to zydeco, you can’t dance – period!... A lot of old people come to my dance, they be havin’ a walking stick, and when they leave the dance they can’t find the stick no more. I say, ‘Quoi qu’arrivait avec ton baton?’ (‘What happened to your stick?’), and they say, ‘Oh, j’ai pas de baton, je l’ai jeté dehors!’ They throwed it outside ’cause they didn’t need it no more!”

Chenier delighted in pleasing his audiences. “Whatever they ask for, if I know it, that’s it, we play it. It makes me feel good if I make them feel good. That’s what you’re there for, not to satisfy you, satisfy the people…. We might go out tonight, and people don’t want to hear nothin’ but the blues. Go out tomorrow night, they don’t want to hear nothin’ but French music. Go somewhere else, they want to hear some hill-billy. I like it all. It don’t make me no difference.” This philosophy remained consistent throughout his Chenier’s career, along with his insistence on playing four-hour sets without taking a break because “I’ve always been a hard worker.”

That showmanship and work ethic helped Chenier persevere as he began his career. After recording for a small company, Elko, in 1954, Chenier went on to record bilingual blues and R&B songs for the national labels Specialty, and then Chess. He toured the country on package shows with such prominent R&B artists as Etta James. However, Chenier’s records didn’t sell well, and by the early ’60s he was back working “the crawfish circuit” between Houston and Lafayette.

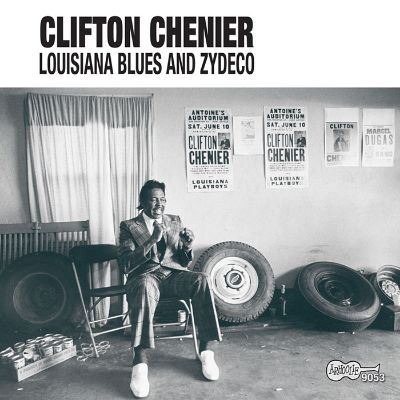

Just when Chenier’s career seemed to have stalled out, he connected with Chris Strachwitz, the owner of the Bay Area–based Arhoolie Records — the best and most simpatico music-business person whom Chenier could have chanced to meet at that point. Strachwitz had founded Arhoolie to release non-mainstream music based on the simple criterion of whether or not he liked it. Strachwitz first recorded Clifton Chenier in 1964, and went on to release eleven more newly recorded albums, plus several 45s. Signing with Arhoolie exposed Clifton to an enthusiastic new audience among young fans of the blues and folk revivals that surged in the 1960s. He became a favorite on those circuits and often performed at festivals in the U.S. and overseas, including 17 consecutive appearances at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, prestigious appearances at Carnegie Hall in New York, the Royal Albert Hall in London, the Montreux Jazz Festival, and the first season of the PBS program Austin City Limits. Even with increasing fame, however, Chenier always stayed connected with his loyal core audience by continuing to play familiar old dancehalls in the Creole communities of Southwest Louisiana and East Texas, such as the Casino Club in St. Martinville.

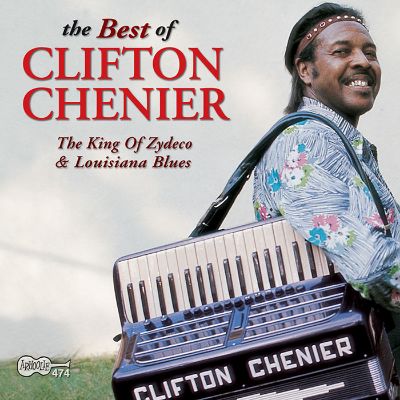

In 1984, Chenier won a Grammy Award for I’m Here in the Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording category. Twenty years later, in 2014, he was posthumously honored with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. Chenier was also the focus of two films by the acclaimed documentarian Les Blank: Hot Pepper in 1973, and Clifton Chenier: The King of Zydeco in 1987. Chenier’s final live performance was at the Lone Star Café in New York City in late November of 1987; he passed away on December 12.

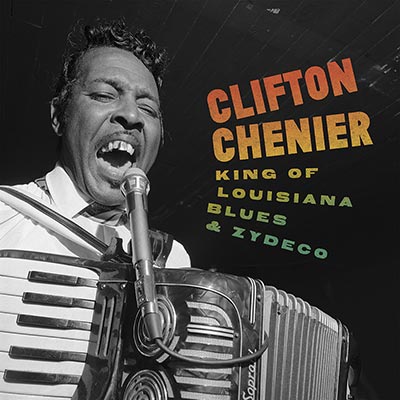

In 2025, 100 years after Clifton’s birth, Smithsonian Folkways, which holds Chenier’s music as a part of their 2016 acquisition of Arhoolie Records, released Clifton Chenier: King of Louisiana Blues and Zydeco, an expansive, comprehensive collection of Chenier’s music produced to celebrate his music and legacy. The box set traces the dynamic and storied career of "The King of Zydeco" from performances in studios and on stages throughout Louisiana, Texas, and California, putting his skill on rubboard, accordion, and vocals on full, vibrant display.

Photo of Clifton Chenier by Chris Strachwitz