Summary

The fandango community celebration is central to the son jarocho tradition of Veracruz, Mexico. This lesson explores the core elements of the fandango: instruments, voice and verse, and rhythmic dance.

Suggested Grade Levels: 3-5, 6-8

Country: Mexico

Region: Veracruz

Culture Group: Mexican

Genre: Son Jarocho

Instruments: Voice, hands, feet, jarana

Language: Spanish

Co-Curricular Areas: Spanish, Social Studies, Physical Education

National Standards: 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9

Prerequisites: Familiarity hearing a wide variety of instruments, knowledge of basic rhythmic notation and 6/8 time signature, lessons on origins of son jarocho (Spanish, indigenous and African influences), including the traditional La Bamba with a few verses

Objectives:

- Listen and identify the instruments, parts and roles in Son Jarocho, including dance as percussion

- Understand the concept of the fandango

- State the traditional function of two common sones: La Bamba and Siquisirí

- Listen to and sing a few stanzas of two Sones: La Bamba and Siquisirí

- Read and tap out notation of a common dance pattern in Son Jarocho

- Explain the concepts of structure and improvisation in lyrics and performance of Son Jarocho, based on Son de Madera's version of Siquisirí

- Improvise and dance a rhythm to La Bamba or Siquisirí

Material:

- Floor space for circle and dance

- Stereo/Sound system with sufficient sound quality to discern instruments

- Several jaranas or ukuleles if available

- CD Track of La Bamba

- CD Track of Siquisirí

- CD Track of Petenera

- Video Son Jarocho

- Video Son de Madera

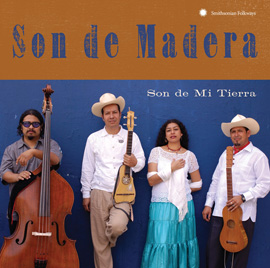

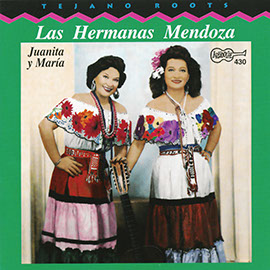

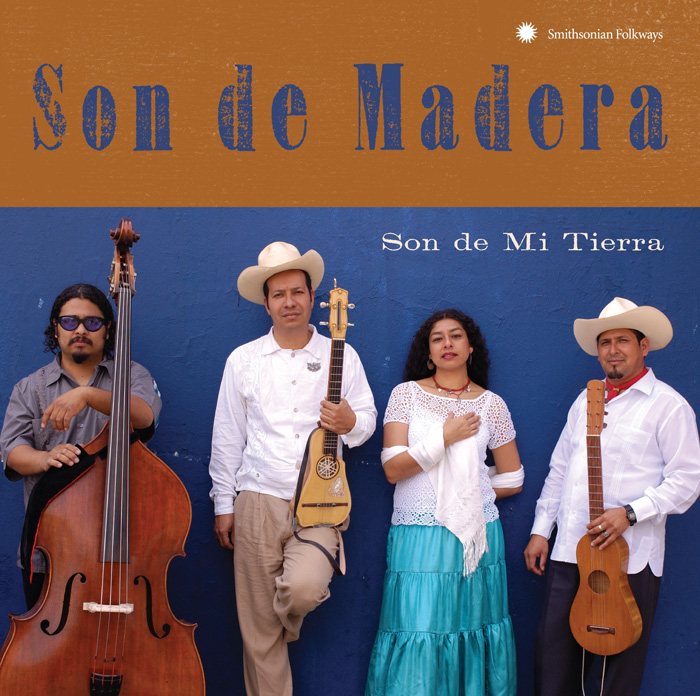

“La bamba (The Bamba)”

from Son de Mi Tierra (2009) | SFW40550

“Siquisirí (Siquisirí)”

“Petenera (Petenera)”

Lesson Segments:

- The Fandango: Community Creation of Son Jarocho (National Standards # 6, 8, 9)

- “Café con Pan”: A Basic Dance Rhythm in Son Jarocho (National Standards # 2, 6, 8, & 9)

- Structure and Improvisation in Son Jarocho Performance (National Standards #1, 6, 8, & 9)

- The Jarana in Son Jarocho: A Basic Jarana Rhythm (National Standards # 2, 5, 6)

- Student Improvisation in a Mini-Fandango (National Standards # 1, 2, 3)

1. The Fandango: Community Creation of Son Jarocho

- Ask the students to listen for how many parts/instruments they hear in the selections “La Bamba” and “Petenera”, from Son de Madera's album Son de Mi Tierra. When they have identified as many instruments as possible, ask them to choose one and pretend play it (like 'air guitar').

- Ask class to name the instruments: harp, voice, “guitars”(jarana, requinto-melodic lead, bass), “tambourine”: (pandereta). Point out the dancers' steps as a kind of percussion, like a drum. Called zapateado, it is a vital instrument in the traditional performance of son jarocho.

- Explain that this music is called. son jarocho, a style of music from Veracruz, Mexico. (Son is a kind of song, jarocho is the name given to people and things from the Mexican state of Veracruz).

- Introduce the Fandango, the traditional context of son jarocho, as a community celebration, where a great many members of the community gather around a tarima (raised wooden platform used as dance floor with percussive resonance) and participate singing, playing and dancing. As the whole community knows the songs and dances, they take turns singing, dancing and reciting verses, often into the wee hours of the morning.

- Show video of Son de Madera performing “El Cascabel”, including sections where they take turns singing and dancing.

- Ask students if/how they experience singing and dancing in their culture.

Extension:

Show pictures of an actual fandango. Ask students to bring pictures of celebrations in their home culture.

Assessment:

Students will define fandango (community celebration) and give at least 3 elements of a traditional fandango (the instuments, singing, dancing, reciting verses). Students will define son jarocho as a kind of music from Veracruz, Mexico. They write their answers as part of an exit slip while the music is playing.

2. “Café con Pan”: A Basic Dance Rhythm in Son Jarocho Style.

- Explain that “La Bamba” was popularized in the United States by Richie Valens in the 1950's, and is a well known song inside and outside of Mexico. (Traditionally, the son “La Bamba” was often played and danced at weddings). Although La Bamba was popularized outside Veracruz, the son “Siquisirí” is as common or even more common in the region of Veracruz. It is played at the beginning of most every fandango in the Son Jarocho tradition. Siquisirí sets the stage for the evening of singing and dancing. The dance form is called zapateado, from the word zapato meaning shoe. Zapateado is a type of dance, common to many parts of Mexico, where stomping the feet keeps percussive time with the music.

- Explain that many sones are in 6/8 time. Play the selection, “Siquisirí” from Son de Madera's Son de Mi Tierra CD. Have students quietly tap out the recurring six beats, including the accented first beat.

- Introduce the phrase café con pan ('coffee with bread', a phrase used to mimic the rhythm of the step) which is used to teach this step, basic to many sones. Replay Siquisirí and clap “café con pan” rhythm to the music, then ask students to join in clapping the pattern. (The accentuation always coincides with how the steps are performed The notation below shows the typical pattern and accentuation of this rhythm in many sones, with the beats corresponding to the syllables “ca” and “con” being strongest. However, unlike many other sones, in Siquisirí, the first syllable “pan” is accentuated).

- Have students then tap the actual step pattern slowly with their hands on their legs as a class saying “LL R L, RR L R, etc.” to the café-con-pan rhythm.

- Moving chairs and tables to side of classroom, or using another suitable space, demonstrate the step. Then, have students practice the“café con pan,” starting slowly with first half of pattern then adding second half. It helps immensely to teach the students as they step with one foot to lift the opposite foot (except with the first of each double step). Have them recite “café con pan,” or “LL R L” as they step.

- Slowly increase the speed of the step until approaching the speed in the recording, then practice with the recording of Siquisirí. (It will most likely take more than one session for any student to master this step).

Extension:

- Further practice of café-con-pan rhythm.

- Teach an alternate “marching” step: one-two-three-rest, five-six-seven-rest.

Assessment:

Students will clap the rhythm of the dance, chant the phrase ‘café con pan’ in rhythm, and dance it to the best of their ability. This can be achieved by asking small groups of students to clap, chant or dance to the music.

3. Siquisirí: Structure and Improvisation of a Son

- The verses of a Son Jarocho usually follow one of a few metric and rhyming forms. A typical form, called décimas, is a ten line stanza of verses that follow a predictable metric and rhyming pattern. Between or directly before beginning a son, participants in a fandango may verbally recite a décima. Using the décima or similar structure, whether spoken or sung, the speaker may improvise verses. Improvising means making up your own words, melody or rhythm that still fits the piece you are performing. In Son Jarocho, the improvisor (called the pregonero if the lead singer) often refers to something or someone in the community. They may comment on a beautiful woman on the tarima, or poke fun at some other member of the community. Watch this video of Son de Madera recording Siquisirí. Ramón Gutiérrez, Patricio Hidalgo and Delio Morales talk about improvisation, and Patricio makes up a décima about his grandfather, a well known pregonero, seen as the father of the renewal of Son Jarocho, who brought it back to its community and fandango roots: video

|

Yo de Arcadio soy el nieto

|

A

|

I am Arcadio's grandson

|

|

Y en mi sangre va su historia

|

B

|

In my blood flows his history

|

|

En mi verso su memoria

|

B

|

In my verse, his memory

|

|

Y en mi cantar su respeto

|

A

|

And in my singing, his respect

|

|

Arcadio fue un claro reto

|

A

|

Arcadio was a clear challenge

|

|

De fandango y porvenir

|

C

|

Of fandango and the future

|

|

Y aunque tuvo que partir

|

C

|

And though he had to part

|

|

Como el agua del granizo

|

D

|

As water from a hailstone

|

|

Yo soy un verso que hizoÂ

|

D

|

I am a verse that he made

|

|

Cuando se negó a morir

|

C

|

When he refused to die

|

- The verses in Siquisirí are not décimas, but “coplas” which also follow a predictable pattern. As in décimas, lines are often 8 syllables long (7 if the last syllable is stessed). Typically, coplas are in four line stanzas, two lines repeated in an ABBA rhyming pattern (common in Son Jarocho). Notice that after the first two four line stanzas, there is a 7 line stanza in this version. A body of verse used by a singer is often referred to as “la versada.” The verses of Siquisirí may speak of love, but also often serve as a prayer for the evening, a welcome or a recognition of those present. Here are the verses sung by Son de Madera with their rhyming scheme. Read out each line in Spanish and have a student immediately read the meaning in English. As best they can, have kids follow the lyrics with their finger as they listen.

|

Le pido permiso al día

|

A

|

I ask the day for permission

|

|

Para empezar la jornada

|

B

|

To start the work of the day

|

|

Para empezar la jornada

|

B

|

To start the work of the day

|

|

Le pido permiso al día

|

A

|

I ask the day for permission

|

|

Quiera Dios que la versada

|

B

|

God willing that the verses

|

|

Tenga valor y poesía

|

A

|

Have courage and poetry

|

|

Tenga valor y poesía

|

A

|

Have courage and poetry

|

|

Quiera Dios que la versada

|

B

|

God willing that the verses

|

|

Ay que sí, válgame Dios

|

C

|

Oh yes, so help me God

|

|

Hermosa perla María

|

D

|

Beautiful pearl, Mary

|

|

Permítame comenzar

|

E

|

Permit me to begin

|

|

Empiezo por saludar

|

E

|

I start by greeting

|

|

Con la música y el verso

|

F

|

With music and verse

|

|

Y aunque el mundo esté disperso

|

F

|

And although the world may be scattered

|

|

Aquí le vengo a cantar

|

E

|

I come here to sing to you

|

|

Para cantar he traído

|

A

|

To sing, I have brought

|

|

Sones de la tradición

|

B

|

Sones from the tradition

|

|

Sones de la tradición

|

B

|

Sones from the tradition

|

|

Para cantar he traído

|

A

|

To sing, I have brought

|

|

Y otros de nueva creación

|

B

|

And others of new creation

|

|

Que a este mundo han venido

|

A

|

That have come into this world

|

|

Que a este mundo han venido

|

A

|

That have come into this world

|

|

Y otros de nueva creación

|

B

|

And others of new creation

|

|

Ay que sí, pero ay que no

|

C

|

Oh yes, but oh no

|

|

Yo me arropo en el cumplido

|

D

|

I clothe myself in the commitment

|

|

Del paisaje que me encierra

|

E

|

To the countryside that surrounds me,

|

|

El que en mi pecho se aferra

|

E

|

That strengthens in my chest,

|

|

y me abriga en el cantar

|

F

|

That protects me on singing,

|

|

Para poder expresar

|

F

|

In order to be able to express

|

|

Los sonidos de la tierra

|

E

|

The sounds of the land

|

- Through call and response, teach the kids to say, then sing the first two stanzas.

Extension 1: Continue teaching verses of Siquisirí. To actually have students learn the verses in this son, it realistically will take more than one session of practice.

- On a subsequent day, continue teaching the verses in this version of Siquisirí in a call and response manner. You can point out that call and response is a characteristic of the singing in Son Jarocho. If you wish, you can show this by replaying the video Son de Madera. In practice, the responder will often vary the tune and reverse the order of the lines. For the learning process, it is best to simply have the students repeat what you say/sing.

Extension 2: Writing Coplas

- Using the 8 syllable line structure, lead the class in writing a 4 line verse in the copla style. This could be done in English or Spanish, depending on the students' language proficiency.

- Have students write their own 4 line coplas in English (or Spanish if they are able). This may be done individually or in pairs.

Extension 3: Improvisation

- Replay the Son de Madera video,and ask students to notice how the jarana player keeps varying his strum to add rhythmic richness to the song. Point out that this is also a form of improvisation. In reality, all the participants improvise within their various roles: the singer may make changes to the verses or melodic line, the dancer adds their own flair to their steps, the requinto player varies the melody he plays, etc.

- Ask students if they know of any contemporary poetry or music styles that use improvisation (jazz, hip-hop). Also raise the specific question where we might find improvised lyrics/verses today (hip-hop).

Assessment:

- In groups of 4, have students sing two verses of Siquisirí. It can also be set up as a game, having one group sing the first, and another responding with the second, in true call and response style.

- Ask students to share their own coplas.

4. The Jarana in Son Jarocho: A Basic Jarana Rhythm (Optional)

This lesson should only be applied if you have access to jaranas, or ukuleles, as a facsimile, and ample time for student practice.

- The jarana is a central instrumental component in Son Jarocho. It is a small, guitar-like instrument with 9-10 strings, most of them double. It provides rhythmic and harmonic body to the son. The role of the jarana is primary, and is more traditional in many parts of the Veracruz region than the harp. There are various sizes of jarana, typically a “primera” (small), “segunda” (medium-sized), and tercera (larger). There are other forms as well.

- The movement used for playing the jarana comes from rotating the wrist rather than any up and down movement of the forearm. The forearm actually rests against the end of the jarana itself.

- There are two fundamental strokes when playing the jarana: the downstroke and the upstroke. The downstroke is played with the fingernails with the fingers held together. The upstroke is played with the back of the thumbnail. Ideally, these strokes should be practiced first in isolation, and then together creating an even up-down rhythm. This in itself requires significant practice. These strokes can be practiced against the stomach as well as on an instrument. If you are using an instrument, dampen the strings with the left hand so all you hear is the rhythm without chords or notes. Chords will be added later.

- Different sones have different rhythms and different jarana strums associated with them. The following is a common basic strum first learned by jarana players

(∏= downstroke, ∨= upstroke):

Double strokes are used to create certain accentuations in the rhythm. In reality, the eighth note strokes are not always perfectly even. There may be slight delays or quickening of certain strokes. This varies from son to son, and gives each son its particular swing or flavor. The strum is actually also related to the steps of a particular son or dancer. In this lesson, however, we won't address these finer points. For our purposes, mastering this basic strum is a good start. This strum can be used with Siquisirí.

Extension:

Add chords and chord changes for the jarana. This will require much teacher guidance, close listening to the music and a number of sessions to practice.

Assessment:

After 2 or three practice sessions, have students demonstrate the strumming pattern in small groups or individually. Since this is a fairly difficult skill, emphasis should be placed on effort and participation.

5. Student Improvisation in a Mini-Fandango

After a few sessions practicing the café-con-pan rhythm, which will likely remain beyond some students capacity to maintain, this segment will provide an experience of the fandango tradition and a chance for the students to engage in a little bit of improvisation.

- Have the students pair off. Replaying the song Siquisirí, give them 5-7 minutes to make up their own zapateado step to the music. They can either prepare them in unison or one responding to the other in their own way.

- Gather students in a circle, as if around a tarima, the raised platform on which dancers dance. (even better if there is a tarima).

Replay Siquisirí, asking the students to sing along. In pairs, have students share their steps. (There is no wrong way in this exercise.) The point is for them to have fun showing “their stuff.” The only rule is to be safe at all times. Give each pair 30 seconds or so. When time comes, teach them to tap the performing pair to let a new pair begin. - Students can take turns playing the jarana rhythm to the music.

Extension 1:

If the students have written their own coplas, invite them to recite them or sing them to the Siquisirí melody as you stage a mini-fandango

Extension 2:

If there are funds to bring in fandango musicians from the community, that would be an ideal way to end the unit. There are fandango communities sprouting up in many cities around the country. Engaging musicians from the community in any of the lessons, for example the dance segment or the jarana segment, lends an important element of connection to real contemporary Latino culture.

Assessment:

As the mini-fandango proceeds, check students off for effort and participation. This can be done as students share their dance “improvisation”, as well as during singing and dancing the traditional words and steps.