Music of Ghana

On March 6, 1957, the nation of Ghana declared its independence, becoming the first formerly colonized sub-Saharan African nation to do so. Formed from the combination of the Gold Coast and Togoland, two former British colonies, Ghana stretches from the dusty edge of the Sahara to the lush rainforests of the Atlantic coast. Prior to contact with European colonialists, numerous ethno-linguistic groups, each with distinct historical and cultural identities, inhabited these lands. Though colonial rule and subsequent African nationalism created a new political and geographical order, the cultural experiences of Ghana's people are still deeply tied to older ways of life. Traditional chiefs continue to retain power over many small claims and domestic issues in rural areas, and Ghana's cultural heritage still reflects its grounding in the greater history of West African civilization. As a result, music remains as integral to the everyday lives of Ghanaians as it has been for centuries. Intensely rhythmic and suffused with meaning, Ghana's many traditions of song, dance, and drumming remain intimately attached to the survival of its communities. Music marks the cycles of life, animates religious rituals, and communicates social values.

Celebrations in Mourning—Funeral Music

Among most traditional Ghanaian societies, death is an occasion not only to mourn loss but also to reflect on and celebrate the life of the deceased. A burial and funeral often last for several days, and are accompanied by songs and dances that move with the event from mourning to celebration. The night following the burial, mourners perform songs of sorrow and grief for the departed. Among the Ewe of southeastern Ghana, vocal ensembles, sometimes accompanied by simple percussion instruments, sing gogodzi to reflect the melancholy atmosphere of the occasion. The Ashanti of central Ghana perform songs in the adowa style, among others, that focus on themes of loss and the chaos caused by death. The second day of the funeral is much livelier, and its music contributes to a greater goal of bringing the community together. "Emo Cman Nkranfo" and "Yazo" are examples of songs from the Ga and Ewe peoples that are specifically designed to stimulate flirtation between younger members of the community. Typically performed by unwed youth of both sexes on the second day of a funeral, these songs reinvigorate the continuation of communal life in the wake of death.

Ritual/Religion

Ghana's religious life is wonderful in its vibrancy. Religious music serves as a crucial element of worship and praise. In abibindwom music of the Fanti people, the translation of Christian hymns into local languages has resulted in an entirely new genre that draws on features of both Christian religion and Fanti drumming. Similarly, groups like Ogoekrom Brass Band No. 2 from Ghana's central region have taken European instruments and hymns and reinterpreted them, creating music that embraces the powerful rhythmic characteristics of Fanti music, and resembles the distinctive sound of the mmensoun ensembles that feature traditional horns made from wood and string or elephant tusks. In some traditional cultures, ritual musical performances enable communication with ancestors by facilitating spirit possession. Songs like that heard on "Agbaja" (and their accompanying dances) carry out this intricate ritual drama, connecting past and present through a medium.

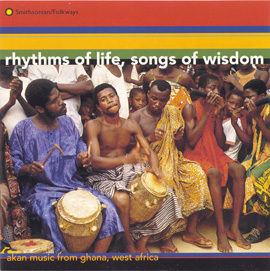

Rhythms of Life

In many ways, Ghanaian music continues to function as a means of creating, defining, and maintaining social identifications. Among the Ewe people of eastern Ghana, women gather after the day's work to sing gbolo or "marriage songs" that speak about their relationships with men and deride immoral relationships in the community. These songs maintain the cultural and moral standards of the group in their very performance. Similarly, music remains central to the privileges and powers of traditional chiefs among a number of ethnic groups. Court musicians can record and recite histories, like that heard on "Talking Drum," or perform in private ensembles like the fontomfrom, a symbol of the chief's status. Even city dwellers from the modern, urban setting of Accra, the nation's capital, create music that carries on folk traditions. The city forms a backdrop for the por por music documented by Steven Feld for Smithsonian Folkways' groundbreaking recording Por Por: Horn Honk Music of Ghana, which chronicles a genre developed by and for Ghanaian truck drivers. Incorporating and manipulating truck horns, tire pumps, and other objects the drivers use, the songs are distinctive expressions of the truck drivers' way of life. On "Shidaa, A Song of Praise and Tribute to Elders and Union Leaders," performers from the La Drivers Union honor their past leaders and tell the story of the creation of por por music. The song thus creates a musical reference that extends and revives the tradition every time it is performed.

Conclusion

Though 50 years old is hardly an advanced age for a nation, Ghana's cultural history remains firmly rooted in ancient traditions. While these recordings represent only a small slice of Ghana's musical heritage, all of Ghana's people, whether from north or south, city or country, live in communities defined by music. The rhythms and melodies of work, play, and sorrow continue to animate the beautiful vitality of Ghanaian life. Even their 50th Independence Day is marked by music. "Por Por Horn-to-Horn Fireworks" was composed by the La Drivers Union Por Por Group to celebrate the momentous day of March 6, 2007.