-

UNESCO Collection Week 5: India – Two Vīṇā Masters

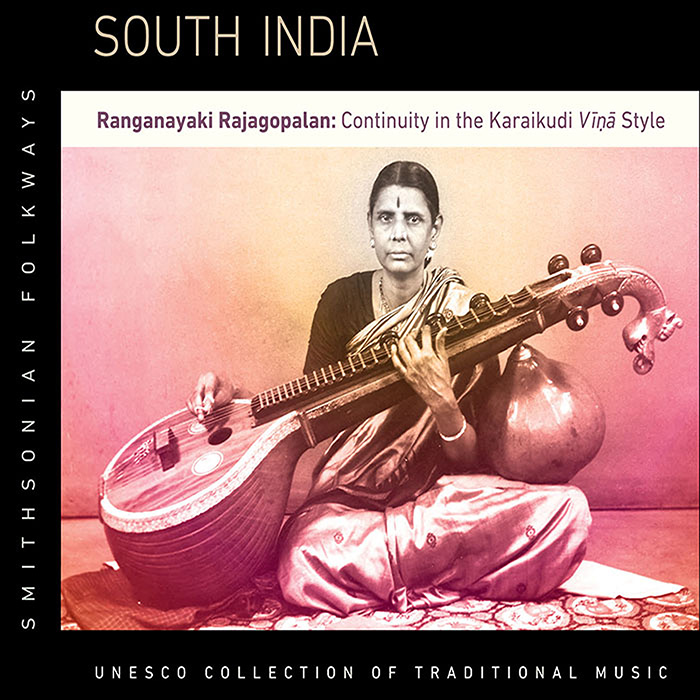

The UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music is being issued two albums per week via digital download, streaming services, and on-demand physical CDs until all 127 recordings are available. Week Five presents masters of two playing styles on the vīṇā, a traditional Indian string instrument. One of this week’s albums is the previously unreleased South India: Ranganayaki Rajagopalan—Continuity in the Karaikudi Vīṇā Style, the first of 12 newly issued recordings in the series.

May 27, 2014

GUEST BLOG

South India: Ranganayaki Rajagopalan—Continuity in the Karaikudi Vīṇā Style

By Richard WolfWhen I first heard the vīṇā, I was drawn to its rich resonance and, as a guitarist, intrigued by the facility with which the performer could bend its strings. I remember being attracted to the exquisite, organic appearance of the instrument, with its graceful curves, nut-brown grain, bone inlay, and gilt carving of the mythical Tamil yāḻi turning its head toward the player—as if this dragon-like creature were listening attentively.

For years I listened to India’s great vīṇā players and looked, mostly in vain, for recordings that captured the intimate sound of their instruments—not the distorted, compromised sound of concert performances but the deep, clear sounds performers themselves hear when they practice or perform in a chamber context.

Capturing just such a sound, this album presents Srimati Ranganayaki Rajagopalan, one of the world’s foremost masters of the instrument at the apex of her career, playing a selection of compositions and improvisations in the sequence they would normally be heard in a concert. Extensive liner notes provide unique access to the history of the performer and her style and scholarly notes describing each section of the performanceAudioI encountered the vīṇā while in college, shortly after my life-changing experience of hearing South Indian music for the first time. My first hands-on experiences with the music were those of learning to play the drum featured on this recording, a double-headed barrel drum called the mridangam. The performer puts a paste of cream of wheat on one head to make it heavier, allowing him to make deep, undulating sounds with the heel of his hand. The center of the other head has a black spot made of slag and rice powder that allows the drummer to tune the head to “sa”—the tonic and drone pitch held throughout a performance.

The drum seemed a natural fit for me at the time because its sounds captured what I wish I could have produced with my own two hands as a restless teenager. I would incessantly and impatiently pound out rhythms on whatever I could find—desks, chairs, tables, books, boxes. After starting to learn the mridangam I recall practicing my lessons everywhere, reciting syllables like “tha ki ta ki ta ta ka dik ku thong gu ki ta tha ka,” rapping my right and left hand fingers against a lamppost as hard as I could. This was one of my favorite pastimes as I made my regular journeys across the US as a hitchhiker in the 1980s. Many years later, more gently, I practiced on the back of my infant son as I put him to sleep. And now, I listen to my boy play those patterns himself on the drum. The drums settle in your bones.

I encountered South Indian music at a time when I was looking for new frameworks to guide my own lead guitar improvisations, and I saw South Indian music as a possible resource for composing. But as I reached deeper and deeper into this music, I became less interested in India as an inspiration for my own artistry and more and more interested in learning about it through participation—playing the music, speaking the languages.

I was extremely lucky in this regard to learn from the most revered vīṇā teacher in Madurai in the early 1980s, Karaikudi Lakshmi Ammal. Her father was Subbarama Iyer (1873–1936), a seventh-generation vīṇā player in a lineage of court musicians and the elder of the esteemed Karaikudi brothers. Smt. Ranganayaki Rajagopalan, under whom I was to apprentice a few years later and from whom I continue to learn, was the senior disciple of the younger Karaikudi brother, Sambasiva Iyer (1888–1958).

Smt. Ranganayaki Rajagopalan is respected for her ability to bring out the essence of Indian melodic modes, called rāgas, with clarity and apparent simplicity. The style in which she plays, the Karaikudi bāṇi, emphasizes capturing the details of integral ornaments, called gamakas. These involve deflecting the string and performing intricate and delicate combinations of hammer-ons, pulloffs, and slides.

Smt. Ranganayaki Rajagopalan is respected for her ability to bring out the essence of Indian melodic modes, called rāgas, with clarity and apparent simplicity. The style in which she plays, the Karaikudi bāṇi, emphasizes capturing the details of integral ornaments, called gamakas. These involve deflecting the string and performing intricate and delicate combinations of hammer-ons, pulloffs, and slides.She has added her own physical touch and creative imagination to compositions she has learned from several vocalists in her lifetime, while carrying forward the famous pieces her guru Sambasiva Iyer refined for the Karaikudi style in his lifetime—such masterpieces as “Mīnākṣi Me Mudam” and “Ĉakkanirāja,” both of which appear on this album. Like all instrumentalists in South India, Smt. Ranganayaki strives to reproduce the sounds of the voice. In the Karaikudi style this is accomplished by plucking with the right hand or the left in places where the vocalist either articulates with a consonant, or provides vocal emphasis on a vowel for the purpose of musical phrasing. In South India today, a fetishization of “the voice” as limitlessly fluid and continuous has led to new instrumental styles that try to do away with many of the forms of attack and articulation that are idiomatic to musical instruments. I believe this has been misguided. Voices and instruments have modeled one another for many centuries in the history of Indian music, and the vīṇā (in many forms) has been the most important instrument through which South Indian music has been conceptualized and described.

Smt. Ranganayaki’s style is rooted in a period long before the development of the microphone. Unlike modern styles in which performers may play prolonged passages after a single pluck on a narrow-gauge string and capture every nuance with the microphone, the Karaikudi style relies on the acoustic resonance of tightly strung, heavy strings. It is a muscular style that balances articulations produced by right and left hands with forms of melodic continuity produced by considerable pressure against the frets. The physicality of music making on the vīṇā comes through on this recording, with the brilliant sound of the instrument captured just as I had wished.

Richard K. Wolf

Professor of Music and South Asian Studies

Harvard UniversityMay 27, 2014

GUEST BLOG

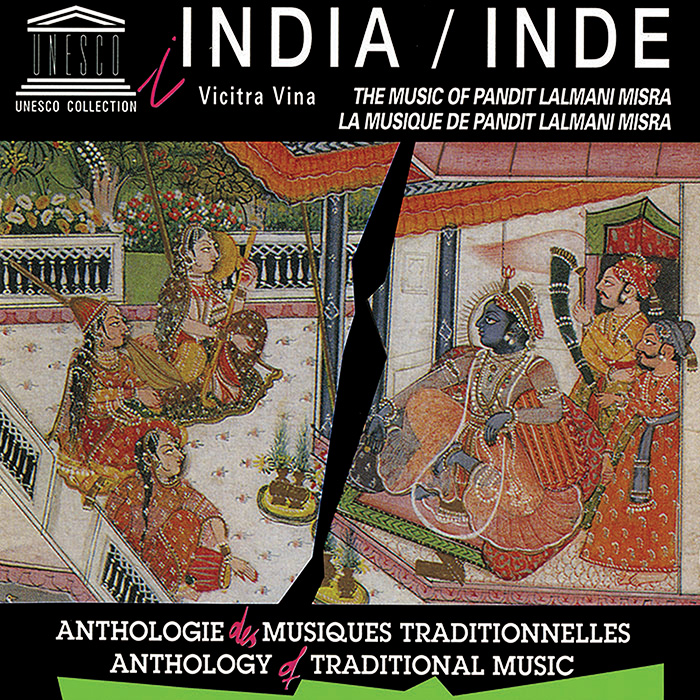

India: Vicitra vīṇā—The Music of Pandit Lalmani Misra

By Morgan BrownOne can marvel at the incredible variety of sounds and songs that can come from a singular instrument. Take for example the vīṇā, humbly defined as a thick, hollow stem with strings resting on two gourds that in the hands of virtuosos achieve disparate yet equally rich expressiveness. Richard Wolf enlightens us on the compelling work of Smt. Ranganayaki Rajagopalan and her mastery in the Carnatic, or South Indian Karaikudi style of vīṇā playing. One can distinguish each instrument when listening to Smt. Ranganayaki, with the vīṇā clearly in the forefront. We are swept into the recording by a consistent and swift rhythm, containing seven sharp counts.

India: Vicitra vīṇā—The Music of Pandit Lalmani Misra features Dr. Lalmani Misra performing Raga “Kausi Kanhada.” Misra blends styles, combining two raga forms: Raga Malkaus and Raga Kanhada. Combined, they offer a series of melodic tones that are consistently ascending and descending slowly. Because the vicitra vīṇā has no frets, it is known for its sliding sound, which adds to the undulating melody. The piece keeps a steady and peaceful pace with agat, or instrumental composition, in slow “Tal Tintal.” But Misra shifts to gat in fast Tal Tintal, where the tablas (drums played by Pandit Ishwar la Misra) are introduced. The pace quickens, but one still hears the same steady melodic climb and fall. Misra presents a magnetic, calm sound until the end.We can compare the work of Ranganayaki Rajagopalan and the Karaikudi style with the vicitra vīṇā. Misra brought the vicitra vīṇā style back to life, as it was practically a lost form of Hindustani playing since the Middle Ages (200 AD – 1200 AD). As a young child in Calcutta (now Kolkata) he began studying singing and harmonium. His mentor was Pandit Gobardhantal, who, amazed by Misra’s talent, encouraged him to involve himself in all musical circles of Calcutta. He became notable for dhruvapad, or dhrupad singing. But the development of chronic sinus problems led him to leave singing behind and become an instrumentalist.

He developed his love for vicitra vīṇā in Lucknow, where he heard musician Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan. His first performance with vicitra vīṇā was soon after this in 1950. From then on, “... vicitra vīṇā was his favorite instrument,” according to producer Dr. Laxmi Tewari. He developed particular techniques of playing, creating new ragas specifically to accompany dhrupad singing. Misra expanded his network by becoming a notable academic. Through his leadership roles in different schools and universities, the vicitra vīṇāstyle of playing had come alive once again by the late 1950s.1

In totality, this performance is close to one hour long, presented as a single track. I imagine that Tewari made this choice for the same reason I enjoy this work so much: the sounds come together as one hypnotic story, one that should not be cut into parts. Similar to South India: Ranganayaki Rajagopalan—Continuity in the Karaikudi Vīṇā Style, this album is dedicated to an artist that flourished within his or her own musical community. Both Lalmani Misra and Ranganayaki Rajagopalan revitalized ancient styles of playing, bringing them into the world of modern Indian music.

Morgan Brown

Intern, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

Georgetown UniversityUNESCO Collection Week 5: India – Two Vīṇā Masters | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings