-

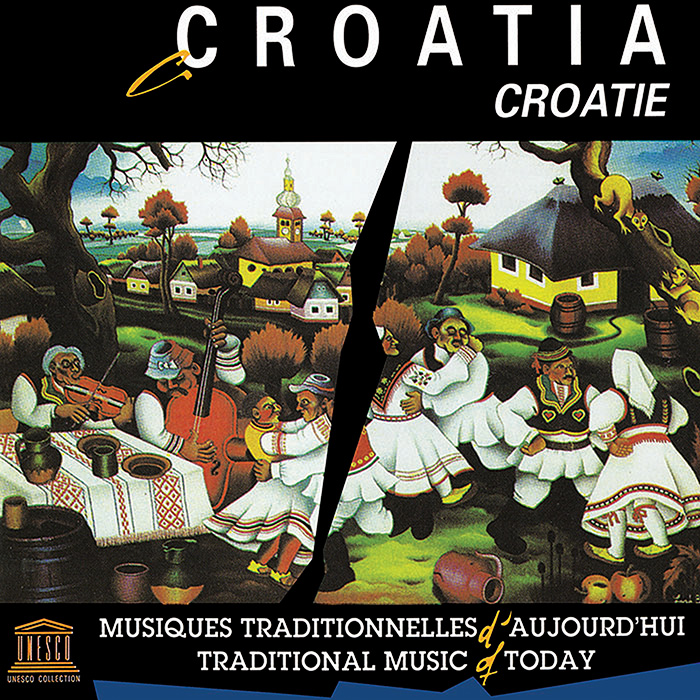

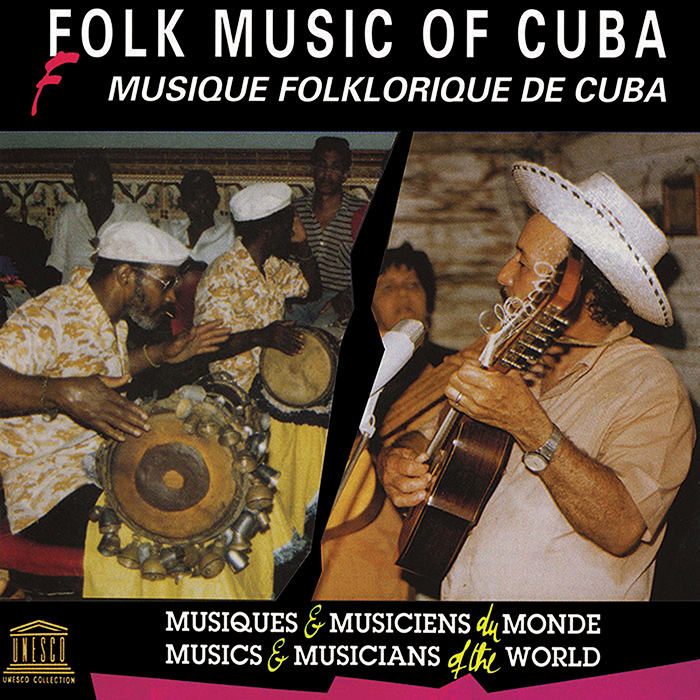

UNESCO Collection Week 60: An overview of contemporary folk music in Cuba and Croatia

Ethnomusicologist, teacher, and performer Andrés Espinoza discusses the evolution of folk music in Cuba and Croatia, emphasizing how ancient traditions remain relevant in contemporary cultures through their ability to evolve in this week’s UNESCO releases, Folk Music of Cuba and Croatia: Traditional Music of Today.

GUEST BLOG

by Andrés Espinoza Agurto

These two recordings document the seemingly unrelated states of tradition in the folk music of Croatia and Cuba. The recordings were made largely in the 1980s (except for some of the Croatian recordings) and allow the listener to assess the development of folk music and musical traditions over the continuums of time (here set in the recent past) and place.

Croatia

Originally released in 1998, these recordings showcase the music of the six main regions of Croatia. As the liner notes state, “the present selection of recordings presents Croatia as a meeting ground of various cultural spheres … The central European/alpine in the west, the Balkan in the East, the Pannonic in the north, and the Mediterranean in the South.” The tracks presented (26 in total) showcase myriad regions and communities, and explore the remarkable diversity of an area at the crossroads of the Eastern and Western worlds. This region, historically a migrant route, presents a unique opportunity to assess the dynamics of traditions, and how the mix of different transient cultures is reflected in the music. These dynamics relate, as stated before, not only to place, but also to time.In placing the documents presented here within the larger understanding of music as tradition, innovation, and the development of traditional culture, some peculiarities emerge. For example, tracks 17-18 show the changes undergone by the same musical style (an a capella round dance) performed by two different generations in the same village. This demonstrates the development of tradition over time. Tracks 23 and 24 are likewise of particular interest to this exploration, revealing the dynamic shifts of place by featuring regional differences and similarities in two interpretations of the same song. The two renditions of “Potpuhnul Je Tihi Vetar” in two different areas (Istrian and Banija) feature extremely different melodic approaches to the same song. As the liner notes say, “in short, apart from the lyrics, it is difficult to indicate any similarities between the performances.”

AudioCuba

Recorded between January of 1984 and January 1989, these selections document a great number of traditions of the Caribbean island of Cuba. There are many musical styles represented in this album, from the rural punto to the son, rumba, and some of the more Afro-centric Cuban traditions, like bata music used during the ceremonies of Orisha worship (Santería), the music of the Congo complex, and the Haitian derived Tumba Francesa. The selections showcase music that ranges from the Western side of the Island (Pinar del Río) to the eastern side (Santiago De Cuba and Guantanamo), also encompassing the central region of Villa Clara, and the oft-explored smaller island off of the southern region of Cuba, Isla de la Juventud. There are also, as one would expect, selections from the two most musically explored regions within the island, Matanzas and La Habana.Some of the selections that show clear influence of Spanish culture in terms of language and organology, such as the punto guajiro, a style typical to the Pinar del Río region, feature guitar-like instruments such as the laúd (lute) and the tres (three stringed guitar)combined with the standard battery of Cuban percussion (bongo, tumbadora (conga), guiro, and maracas). Tracks 1, 2, and 3 feature the countryside style of punto guajiro. The three tracks (though two of them were recorded in La Habana) demonstrate the fixed poetic form of décima, the dance based zapateo and the free meter style of the tonada. In contrast to the more Hispanic, string-based selections, tracks 4, 8, 11, and 13 present music more connected to Cuba’s African roots via drumming and chanting in languages other than Spanish. Track 4, for example, features the Enkame, an oral narrative performed during the Abakuá rituals. The selection features legendary singer Gregorio Hernandez, known as “El Goyo,” and drummer Justo Pelladito.

AudioTrack 8 is a performance of a section of one of the larger rituals of Santería, and a great example of the Afro-centric music in Cuba. This recording shows the instrumental “Oru Igbodu” as performed by the bata ensemble of Amado Diaz in the Matanzas region.

AudioThe complete set of recordings has great relevance as it documents the state of several Cuban folk traditions at a time when popular music (e.g. Los Van Van, Irakere, Ritmo Oriental, etc) had taken over the Cuban music scene, with folk music becoming mainly a cultural referent rather than an item of great popularity.

Within the exploration of the dynamics of tradition, it is interesting to compare these recordings with earlier releases of Cuban folk music which feature many of the same musical traditions. Verna Gillis’ recordings from 1978-79, released as Music of Cuba on Smithsonian Folkways (FW04064 / FE 6064), give a great point of comparison as they were made within the same general time period. It is, however, even more interesting to draw comparisons with the earlier Smithsonian Folkways recordings of Cuban music, such as the Harold Courtlander recordings featured on the Folkways release Cult Music of Cuba (FW04410 / FE 4410), or Lydia Cabrera and Josefina Tarafa’s 1957 recordings of Afro Cuban music (Havana, Cuba, ca. 1957: Rhythms and Songs for the Orishas (SFW40489); Matanzas, Cuba, ca. 1957: Afro-Cuban Sacred Music from the Countryside (SFW40490); Havana & Matanzas, Cuba, ca. 1957: Batá, Bembé, and Palo Songs (SFW40434)). In comparing all of these recordings, different musical snapshots of similar or, in some cases, identical repertoires allow for a great deal of analysis in regards to the evolution of traditional Cuban music.

Both albums are a great testament to the state of traditions in the recent past, their evolutions and ever shifting dynamics. These albums are not only a fantastic musicological document, but are also extremely relevant in that they offer a challenge to the notion of folk music as a set of static traditions, not suitable to differing musical interpretations, and somehow set in a distant ‘atemporal’ past.

A native of Chile, Andrés Espinoza Agurto has been playing percussion since he was 8 years old. He studied Afro-Cuban percussion at the Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA) in La Habana, Cuba, graduated summa cum laude from Berklee College of Music, receiving a BM in Jazz Composition, and holds an MM from the University of York (England). He received his PhD in Ethnomusicology from Boston University in 2014. His dissertation is entitled Una Sola Casa: Salsa Consciente and the Poetics of the Meta-barrio, and analyzes the impact of Salsa music as a forging element of social and political identity within Latino and Latin American communities. Other research interests include the application of ethnomusicology to jazz performance and composition, Afro-Latino music, and Spanish language rap. He is also the composer, musical director, and percussionist of the Andres Espinoza World Jazz Ensemble, the Andres Espinoza Octet, and the Latin fusion sextet Los Songos Jalapeños.

UNESCO Collection Week 60: An overview of contemporary folk music in Cuba and Croatia | Smithsonian Folkways Recordings