-

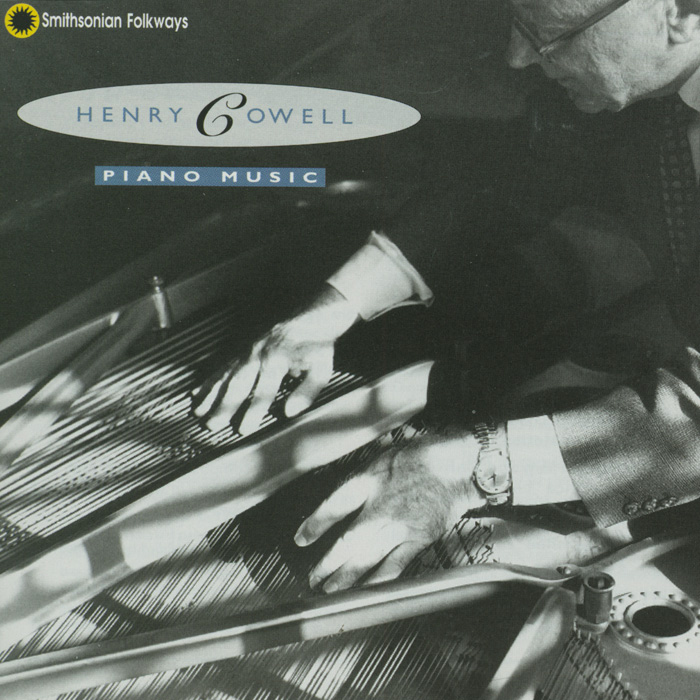

Year of Recording: 1993Year of Recording: 1980Year of Recording: 1957Archive SpotlightHenry Cowell: Mellifluous Cacophony and Its Legacy

Year of Recording: 1993Year of Recording: 1980Year of Recording: 1957Archive SpotlightHenry Cowell: Mellifluous Cacophony and Its Legacy

Henry Cowell wrote hundreds of piano compositions in which he notated the use of extended technique, where the performer plays with their fists, forearms, and palms, in addition to fingers. Whether seeking the mellifluous, thunderous, or cacophonous, Cowell rarely strayed from using these masses of adjacent second tones as underpinning (or overpinning, with melody in the bass) for lyrical lines. These groupings of white key chords or chromatic half tone clusters became the secundal or polyharmonic sounds that crept into modern jazz piano and a wide variety of ensembles over the course of the 20th century.

Cowell’s concert tours in the U.S. brought many Americans their first taste of modern music and experimental piano techniques. I began performing Cowell’s piano music in 1968, playing thousands of performances between then and 1989, when my own composing took over. I remember as a young pianist performing some of my cluster favorites like “Advertisement” and “Tiger” in Chattanooga around 1970. An elderly woman approached me afterward with a smile on her face. She recalled seeing Cowell perform these same pieces at her Music Club Gala in the 1920s, where he also explained to the audience how to perform this astonishing new sound.

As a young composer, Cowell rolled a darning egg across the piano strings. He plucked the strings, he strummed the strings, and he made the strings roar in pieces like “The Banshee” and “Aeolian Harp”. However, his later piano music pulled back from extended playing technique. Already in a piece called “Maestoso” he was calling on the ten fingers to do what he earlier might have used a palm or forearm to play.

Cowell was generous to his colleagues and to younger composers. Through his magazine New Music and New Music Quarterly Recordings he exposed the musical scores and cultural philosophy of many musicians to a wide audience. Among those who he actively promoted were Ruth Crawford, who explored atonality in the 1920s, and John Cage, who forayed further into the piano’s interior with his “prepared piano” compositions in the late 1930s and ‘40s.

Cowell was the first American pianist to tour Soviet Russia. Though it may be apocryphal, some Eastern Europeans swear that the secundal harmony used by Poles Krzysztof Penderecki and Witold Lutoskavski, and by Hungarian György Ligeti, was influenced by the concerts of Henry Cowell in Europe.

I see Cowell’s “Concerto for Piano and Orchestra” as the climax of his experimental piano years. It uses hybrid tonal mixing: diatonic harmony, atonal yearning, and many tonal murmurings. The piano cluster sequences are atmospheric in the second movement and brickbat percussive in the third movement. But what about the orchestra? It, too, has that bottom to top layering of harmonies, which we know better from the orchestral music of Charles Ives. Cowell was a champion of Ives when Ives was ignored by colleagues and despondent at the lack of attention to his music. Henry Cowell and his wife Sidney wrote a book on Ives, so intrigued were they by the early polytonal experimentation of Ives and convinced that Ives’s music had a vital place in American music.

We composers learn from each other—steal from each other, if you like. It was certainly my early performing of Henry Cowell’s music that propelled me into electronic music, with all its microtonal possibilities. Cowell tried the eerie electronic theremin in the 1930s, but did not partake in the electronic music explosion that took place after World War II, which included tape recorders and computers. If he had had the advantage of synthesizers such as the DX-7 with its chromatic glissandi, and the outrageously versatile sound samplers and virtual synths of our present time, what might he have done?

My early piano compositions began with Cowellian tonal clusters and interior string damping. One piece that I composed in 1974, “Sunday Nights”, was a mixture of hymn melody, atonal cluster and plucked note sequences married with repetition—akin to what Cowell played in the middle section of “Advertisement”, where the performer may use their personal discretion to repeat as many times as they want.

In 1963, I bought my first tape recorder, a tiny Roberts. In 1966, I bought an Uher, which allowed for some really sophisticated tape splicing that carried me all the way through the decade, until Donald Buchla invented his wonderful music machines. Blessed with early access to Buchla synthesizers in 1972 at the Queens College Electronic Music Studio, I quickly transposed my piano clusters into blends of traditional piano sounds with manipulation and activation of electronic sound. I used a Barcus Berry transducer microphone on the grand piano soundboard in a set of pieces called “Wildflowers”, where the piano triggered the Buchla electronics. I then spent years touring Europe with my Samsonite encased custom Buchla synth, recording for Bremen Radio and playing Buchla-piano pieces in Zagreb, Trieste, Amsterdam, and Munich.

When I found out how easily I could track rhythms and inflections of speech using contact microphones on the throat and running these sounds through my Buchla synth, I began tracking regional dialects of the Southern U.S. This led to the Southern Voices project, where I used tape music and spliced vocal recordings to create “documentary music” about the South. Selections from this project are represented on the Folkways recording Voicings. I later translated this work into vocal song and orchestral melodic lines, which culminated in a commissioned piece for the 50th anniversary of the Chattanooga Symphony called “Southern Voices for Orchestra”.

It was Cowell’s inclination to avoid conventional techniques and revel in the mixtures of melody and tonality that made me love playing his piano music. To this day, all 75 years of days, I sit down at the piano and get a kick out of showing someone the glories of sound in one of his grandest pieces “The Harp of Life”.

Sorrel Doris Hays is a musician, composer, and educator. Her Southern Voices project, which was supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, resulted in the album Voicings (Folkways, 1983) and the documentary Southern Voices: A Composer’s Exploration (DER, 1985). Her book Touching Sound Living Lullabies provides a multicultural perspective on music and physiology. She has written numerous musical dramas about females, with topics ranging from honey bees to valiant women.