-

Cover Story¡Que Viva la Música Latina!

Cover Story¡Que Viva la Música Latina!

In 1982, the National Endowment for the Arts launched its annual National Heritage Fellowship award program, putting a major spotlight on renowned traditional artists from across the United States and its territories. Having been a member the Folk & Traditional Arts program staff from 1978 to 2000, I was witness to that exciting time. There was a good deal of handwringing in the early years of the awards. Our program’s director, Bess Lomax Hawes, and our many folklife advisors were concerned that in singling out one person or group representing a communal tradition, the highly visible federal recognition might inadvertently cause more harm than good by disrupting the local cultural ecology. There was also concern that in a nation of hundreds of folk traditions, recognizing only a handful of artists each year might have the effect of marginalizing the many traditions not represented.

With an eye toward these concerns, the program guidelines were carefully crafted to take three factors into consideration when reviewing nominations: artistic excellence, authenticity, and impact on his or her cultural community. “Excellence” did not mean that the candidate for the award needed to be “the best” in his or her tradition, but rather at the top level of artistic achievement in that tradition. By “authenticity” (a troublesome term for many people), we meant that in the minds and hearts of a cultural community, the awardee should be a touchstone of tradition—that is, the artist should represent a body of practice larger than him or herself, as opposed to highly individualistic expression outside of the boundaries of tradition. “Impact” gauged the artistic influence and positive effect the artist had within the tradition. Also, especially in the first few years of the program, the experts who reviewed the candidates for the award scrutinized the award-giving to ensure that the nation’s signature national, regional, and tribal traditions did not escape their attention. With all this in mind, thirty-five years later, it is interesting to see how the program, now regarded as “the federal government’s highest award in the folk and traditional arts,” unfolded.

The view of the program’s first decade through the prism of American Latino music awardees is telling, and fortunately, much of the story can be heard through the recorded collections of Smithsonian Folkways. In the first year, 1982, Texas Mexican songster Lydia Mendoza was among the fifteen awardees representing as many traditions of craft, verbal lore, dance, and music. The Tejano song tradition was deeply rooted in the southern border region, and Mendoza, known widely as “La Alondra de la Frontera” (The Lark of the Borderlands), was clearly its most renowned representative. The next year saw two other prominent, longstanding regional music traditions in the line-up: accordion-driven Texas Mexican conjunto music represented by accordion pioneer Narciso Martínez of San Benito, Texas; and Afro-Puerto Rican bomba and plena, embodied in the musical dynasty of the Cepeda family led by its patriarch Rafael Cepeda. Martínez’s musical partner, bajo sexto player Santiago Almeida, would receive the award in 1993, and Cepeda’s role model would shape the work of later awardees in the tradition, such as 1996 honoree Juan Gutiérrez, founder of Los Pleneros de la 21 in New York City.

In 1984, the spotlight turned in yet another direction, to the centuries-old Hispanic musical forms of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Cleofes Vigil, carrier of an ancient song repertoire, was the tradition’s first recipient, followed in 2003 by the father-son duo Roberto and Lorenzo Martínez representing the regional instrumental music traditions and corrido ballads telling of the heroic exploits of Nuevo Mexicanos. In 1985, the other principal signature Puerto Rican music tradition was brought to the fore: música jíbara (music of the rural mountain people known as jíbaros), through instrument maker-musician Julio Negrón Rivera. Two more Tejano accordionists, Valerio Longoria and Pedro Ayala, followed in 1986 and 1988, respectively, pointing to the music’s national significance and longevity. In 1989 and 1990, two regional traditions from Mexico which had become part of the fabric of American cultural life were showcased. Since the 1950s, the son jarocho, originating in Veracruz, Mexico, had been part of the soundscape of Southern California, and immigrant musician José Gutiérrez was a respected performer, accomplished instrument maker, and influential teacher. In 1990, the NEA honored Natividad “Nati” Cano, who had immigrated to the U.S. from the Mexican state of Jalisco to become the leader of the renowned Los Angeles-based ensemble Mariachi Los Camperos. Cano had long set the standard for mariachi performance in the United States, and he was key to the resurgence of mariachi music performance in festivals and schools across the nation. To wrap up the program’s first decade, Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero of Tucson, Arizona—an influential singer, composer, and bandleader in the early days of homegrown Mexican American music in Southern California—was among the awardees in 1991.

Viewed in this historical context, the National Heritage Fellowship program was successful in staking out early on the main contours of Latino musical tradition in the United States. The following quarter century of awardees for the most part saw additional awardees in these bedrock Latino music fields, including Tejano accordionists Leonardo “Flaco” Jiménez, his brother Santiago Jiménez, Jr., Antonio “Tony” De La Rosa, and Domingo “Mingo” Saldívar. In other cases, other niches of musical practice were honored, such as the son huasteco Mexican regional style of Artemio Posadas, and music of the Chicano civil rights movement, performed by Ramón “Chunky” Sánchez and Agustín Lira. Overall, these and the other Latino National Heritage Fellows paint a vivid picture of the rich and varied mosaic of Latino music in the United States and Puerto Rico.

We invite you to discover this music for yourself by listening to the playlist below which samples thirty-five years of U.S. Latino musical heritage.

The son of Tejano conjunto pioneer accordionist and composer Santiago Jiménez, Sr., Flaco Jiménez rose to be the most renowned of the Tejano accordionists from the late 20th century onward. This song, written by his father, was the lead title of the 1987 Arhoolie album that won him the first of several Grammys. Flaco was also recognized by the Recording Academy in 2015 with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

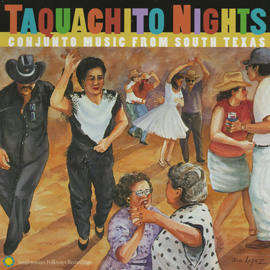

Button accordion player and composer Narciso Martínez was among the earliest of prominent Tejano accordion players. His primacy, along with his longlasting creativity, earned him the honorific nickname “The Father of the Texas Mexican Conjunto.” Right at his side, though, was another National Heritage Fellow―Santiago Almeida. Almeida was the master of the weighty, twelve-stringed guitar called the bajo sexto, which played both bass notes and chords. Together they set the “DNA” of the style, which remains the core of the tradition to this day. Polkas such as this 1946 piece “Muchachos alegres” have long been mainstays of the Tejano conjunto repertoire.

Tejana songster Lydia Mendoza made a name for herself starting in the early 1930s, singing in the Plaza de Zacate (Haymarket Plaza) of San Antonio and accompanying herself on the twelve-string guitar. Her voice became a signature sound of Tejano identity, and she was given the title “La Alondra de la Frontera” (The Lark of the Borderland). Some accounts claim she learned this Argentine tango-influenced song from lyrics printed on a bubble gum wrapper. She was among the first National Heritage Fellows in 1982.

José Gutiérrez immigrated to the United States from the ranchlands of Veracruz, Mexico, where he made a name for himself as a prominent practitioner of the regional music known as son jarocho. In the United States, he toured widely, was artist-in-residence at the University of Washington, and taught many apprentices his skills of both performing and making the three main jarocho instruments of harp, requinto (melody guitar) and jarana (rhythm guitar). Today, José has retired to his Veracruz homeland, though still performs regularly both in Mexico and the United States. “Siquisirí” often opens a performance of son jarocho, be it on a concert stage or in a house party.

Artemio Posadas was honored with the Bess Lomax Hawes National Heritage Fellowship in 2016, recognizing his work as cultural advocate and community organizer as well as musician in the tradition of the son huasteco. The son huasteco, notable for its use of falsetto voice to adorn the melody, is native to northwestern Mexico and practiced in Mexican American communities in California. This recording of “El caballito” illustrates his work. He wrote the poetry for and produced the recording El ave de mi soñar with the renowned trio huasteco Los Camperos de Valles, and he sang lead voice on this track.

Northern New Mexico is home to the most ancient of Hispanic music traditions from the United States. Cleofes Vigil, from the village of San Cristóbal in the northernmost reaches of the state, wrote this rustic, solo ballad in the form of an indita, a colonial-era genre of music. He accompanies himself on the mandolin.

Guitarist-composer Roberto Martínez and his violinist-arranger son Lorenzo were awarded a National Heritage Fellowship jointly for their many years of collaboration and advocacy for their Hispanic music from northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. They played old-time dance tunes and traditional songs, as well as corridos (narrative ballads) written by Roberto. This corrido, among his best known, tells the tale of selfless courage on the part of New Mexican American serviceman Daniel Fernández, who during the Vietnam War threw himself on top of a live grenade, sacrificing his own life to save those of his fellow soldiers.

In the 1960s, the farmworkers movement in California and the Southwest saw Chicano activism come to the fore of American life and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement blossom alongside the African American Civil Rights Movement. Delano farmworker Agustín Lira was part of both these important social change makers, as he first co-founded the activist theater group Teatro Campesino as part of the United Farmworkers union, and then went on to be a leader in the broader struggle for Chicano pride and civil rights. “Quihubo Raza” is one of his signature compositions, saluting his Chicano listeners and drawing their attention to the need to understand and confront injustices they have suffered.

Nati Cano looked to the tradition of mariachi music which he inherited from previous family generations as a way to build respect for Mexican heritage in the United States. His Grammy-winning group, Mariachi Los Camperos de Nati Cano, earned Grammy awards and other accolades for their high level of artistry. The National Heritage Fellowship also recognized his enormous efforts and impact in teaching the tradition to tens of thousands of young people throughout the United States. The song “Llegaron los camperos” was ready-made to be the opening fanfare for thousands of his concerts.

Tejano conjunto accordionist-composer Tony De La Rosa marked a new era of conjunto music with his slow-paced polka beat that accompanied a gliding dance step called tacuachito (little possum, referring the characteristic stride of the possum). His recording of “Atotonilco” with its staccato accordion playing stands as a signature piece of his that points to the sound that would influence generations to come.

Mingo Saldívar and his conjunto the Tremendos Cuatro Espadas kept the conjunto “traditional” while accommodating his music to urban San Antonio tastes. The cumbia dance rhythm, heard here, made it to Texas from South America and Mexico, and Saldívar made it his own. He allowed greater freedom in the bajo sexto’s playing and often added English lyrics, in keeping with his bilingual audiences. He is also a natural showman, encouraging his listeners by dancing onstage.

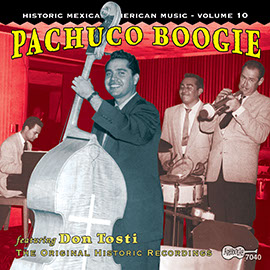

Lalo Guerrero was a pillar of urban Chicano music creation. From Tucson, Arizona, he relocated to Los Angeles and wrote a seemingly endless stream of pieces that captured urban Mexican American style and identity in the 1940s and 1950s. The dress fashion and cultural style of look of pachucos were featured in Luis Valdez’s musical Zoot Suit, which drew from Guerrero’s work. This “pachuco boogie” epitomizes the sound. Guerrero also was honored with a National Medal of Arts after he received the National Heritage Fellowship.

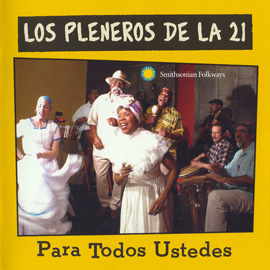

A driving force in the renaissance of Afro-Puerto Rican music in the late 20th century, the New York City-based group Los Pleneros de la 21 was founded by percussionist Juan Gutiérrez. Gutiérrez drew from musical elders in NYC and Puerto Rico to infuse the musics called plena and bomba with the strongest strands of Puerto Rican tradition available. Also, as may be heard in this arrangement of the plena “Carmelina,” he also invited contemporary jazz and salsa musicians such as trombonist Ángel “Papo” Vásquez and cuatro player Edgardo Miranda to add their creative sounds to the mix.

Daniel Sheehy is director and curator emeritus of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, having served from 2000 to 2016, and again as interim director from 2020 to 2023. As director of Folk & Traditional Arts at the National Endowment for the Arts (1992-2000) and staff ethnomusicologist and assistant director (1978-1992), he directed the National Heritage Fellowship awards and grants programs. In 2015, the NEA awarded him a Bess Lomax Hawes National Heritage Fellowship.